Cashing in on Counterfeits:

Fraud in the Reformation Print Industry

This article explores the widespread counterfeiting of Martin Luther’s works during the Protestant Reformation, with a particular focus on the inclusion of false Wittenberg imprints on title pages. Printers took advantage of Wittenberg’s association with Luther and the Reformation movement to enhance the market appeal of their publications. Through a systematic examination of counterfeit editions, the article analyzes the deceptive practices employed by printers across early modern Europe. It also discusses Luther’s attempts to combat counterfeiting and the role of misleading imprints in the buying and selling of books during that time. The study reveals the significant role of fraud in the success of the Protestant Reformation and sheds light on the marketing strategies employed by printers in the era.

Notice: This document is a post-peer review author accepted manuscript of Drew B. Thomas, “Cashing in on Counterfeits: Fraud in the Reformation Print Industry” in Shanti Graheli (ed.), Buying and Selling: The Business of Books in Early Modern Europe (Leiden: Brill, 2019), pp. 276-300. It has been typeset by the author and is for informational purposes only. It is not intended for citation in scholarly work and may differ in content and form from the final published version. Please refer to and cite the final published version, accessible via its DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004340398_015.

Martin Luther was interrupted one evening in 1525 with some disturbing news. His manuscript for a new collection of sermons had been stolen by an assistant and taken to a printer in a neighbouring town.1 Luther’s works were in high demand and printers knew they would sell quickly; a first edition was a prized possession. This troubled Luther, as he knew there were many unauthorized copies of his works, but feared their inaccuracies corrupted his Reformation message. Yet even at the height of his fame, there was little he could do.

That same year during the German Peasants’ War, Luther published An Admonition to Peace: A Reply to the Twelve Articles of the Peasants in Swabia. It was an extremely popular work with thirteen editions that year alone, ten of which were printed in Luther’s hometown of Wittenberg. At least that is what printers wanted you to think. In reality only three editions were printed in Wittenberg.2 The rest were counterfeits.

Luther’s Protestant Reformation caused a surge in printing activity across early modern Europe. By 1521, only four years after he posted his Ninety-Five Theses, more books had been published by Luther than any other author since the invention of the printing press in the mid-fifteenth century.3 Due to the growth of the industry many new printers entered the trade, hoping to make their fortune. Many participated in a widespread practice of re-printing unauthorized copies of popular editions. This was a common and accepted practice within the industry at this time. However, many printers took it a step further. In addition to unauthorized reprints, several printers intentionally printed false publication information on the title page. This was particularly true when it came to Wittenberg. During Luther’s lifetime, hundreds of editions were printed that were falsely attributed to Wittenberg. The practice was prevalent across Europe, encompassing the Holy Roman Empire, the Swiss Confederation, the Low Countries, and even reaching all the way to London and Paris.

While there have been documented cases of piracy of other printers or authors this is the first case in which a single printing city was the focus of such widespread fraud. Wittenberg was the fulcrum of the Reformation movement and its presence on the title page brought authority and authenticity to a document. Printers recognized this and used it to their advantage. They knew that works from Wittenberg sold well and that their works were more likely to sell well too if thought to be from Wittenberg. They accomplished this by printing ‘Wittenberg’ on their title pages and omitting the truthful city of publication.

In 1895, the bibliographer George Frederick Barwick noted a wide variety of typefaces used in the large number of Wittenberg pamphlets in circulation. He concluded that Wittenberg imprints could not be trusted.4 He was correct. The reason there was such a large variety of typefaces was because they belonged to around seventy different printers who published counterfeit Wittenberg editions. Hans-Jörg Künast also remarked upon this practice in his analysis of the Augsburg printing industry.5 Although this phenomenon has been remarked upon before now, it has never been subject to systematic investigation. In this essay I attempt the first systematized examination of these counterfeits by dividing them under four categories: works that were false by association, false by implication, simple counterfeit, and advanced counterfeit. This essay offers a methodological discussion of each category, with practical examples. It then presents different ways in which Luther and the printers of Wittenberg attempted to fight the counterfeits, which was made more difficult by wider geographical distribution. The concluding section offers some broader considerations about the role played by misleading or fraudulent imprints in the buying and selling of early modern books.

False by Association

Numerous Reformation pamphlets were printed that provide no publication information. Sometimes the year was listed, but the printer and place of publication were absent. Even Wittenberg editions often excluded the place of publication. At this point there was no standard practice in the German print industry. However, even if the place of publication was omitted in Reformation pamphlets, printers were still sure to include ‘Wittenberg’ on the title page, but not necessarily in the imprint. Rather, they listed ‘Wittenberg’ at the end of the title, using phrases such as ‘Doctor Martini Luthers Augustiner zu Wittenberg’ or ‘Predig zu Wittenberg’. This was especially common at the beginning of the movement, when Luther’s name was not as well known, but people were aware of a movement by an Augustinian monk in Wittenberg. These works were published sometimes with or sometimes without a colophon. Regardless, Wittenberg was often the only city mentioned on the title page.6 While there was no intent to deceive, as there was no untruthful information printed, printers were clearly keen to associate their work with Wittenberg.

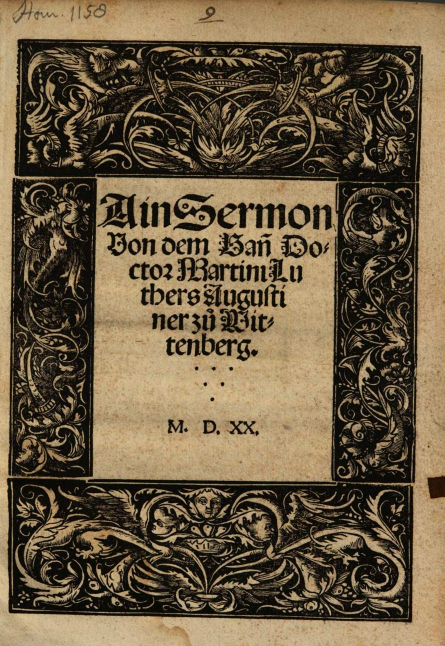

In 1520 the Augsburg printer Silvan Otmar printed a controversial sermon by Luther on excommunication.7 The title page is in a large typeface surrounded by a four-piece, floriated woodcut title page border. Only the year is listed in the imprint. However, the title ends with ‘zu Wittenberg’ broken over two lines of text. It is the only city mentioned on the title page (Figure 15.1).

Another edition of that sermon was printed in Nuremberg.8 This title page is much simpler with no woodcut border or imprint. There is only a three-line title with the first line in a larger typeface. In this example, ‘Wittenberg’ is also listed at the end of the title: ‘Augustiner zu wittenbergk.’ Although the typeface is smaller, ‘Wittenberg’ is not split over two lines, as in the previous example. This improves the visibility of the word, thus making it more recognisable

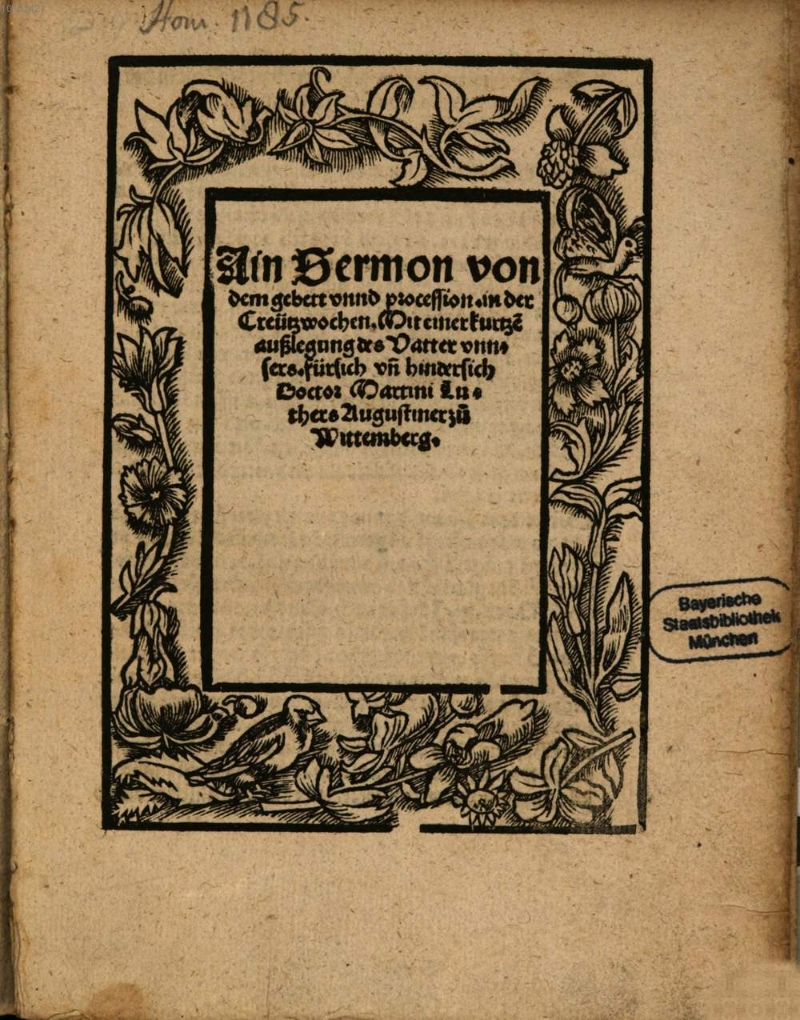

We may also cite the example of a work published by Hans Froschauer in Augsburg in 1519.9 It also has a title page border and a title with the first line in a larger typeface. There is no imprint. In this example ‘Wittenberg’ is the last word of the title and the only city mentioned on the title page. Unlike the previous examples, ‘Wittenberg’ is on a line by itself. The decreasing center alignment of the title, giving an upside-down triangle appearance, guides the eye to ‘Wittenberg’ (Figure 15.2).

These printers were not deceiving the reader with false information, as they are only stating Luther was from Wittenberg. But by omitting publication information, Wittenberg becomes the focus of attention, and a selling point.

False by Implication

Unlike the previous category, this group of Wittenberg counterfeits represent a deliberate attempt to deceive the reader. These editions have a false imprint, but list the real print city in the colophon. Printers highlighted Wittenberg on the title page instead of the actual city to imply the work was from Wittenberg. ‘Wittenberg’ is separated from the title, often in larger type, sure to grab the attention of the buyer. Barwick states that he never discovered any editions with a false Wittenberg imprint that listed the actual printer.10 However, I have identified numerous examples with false imprints that have a truthful colophon.

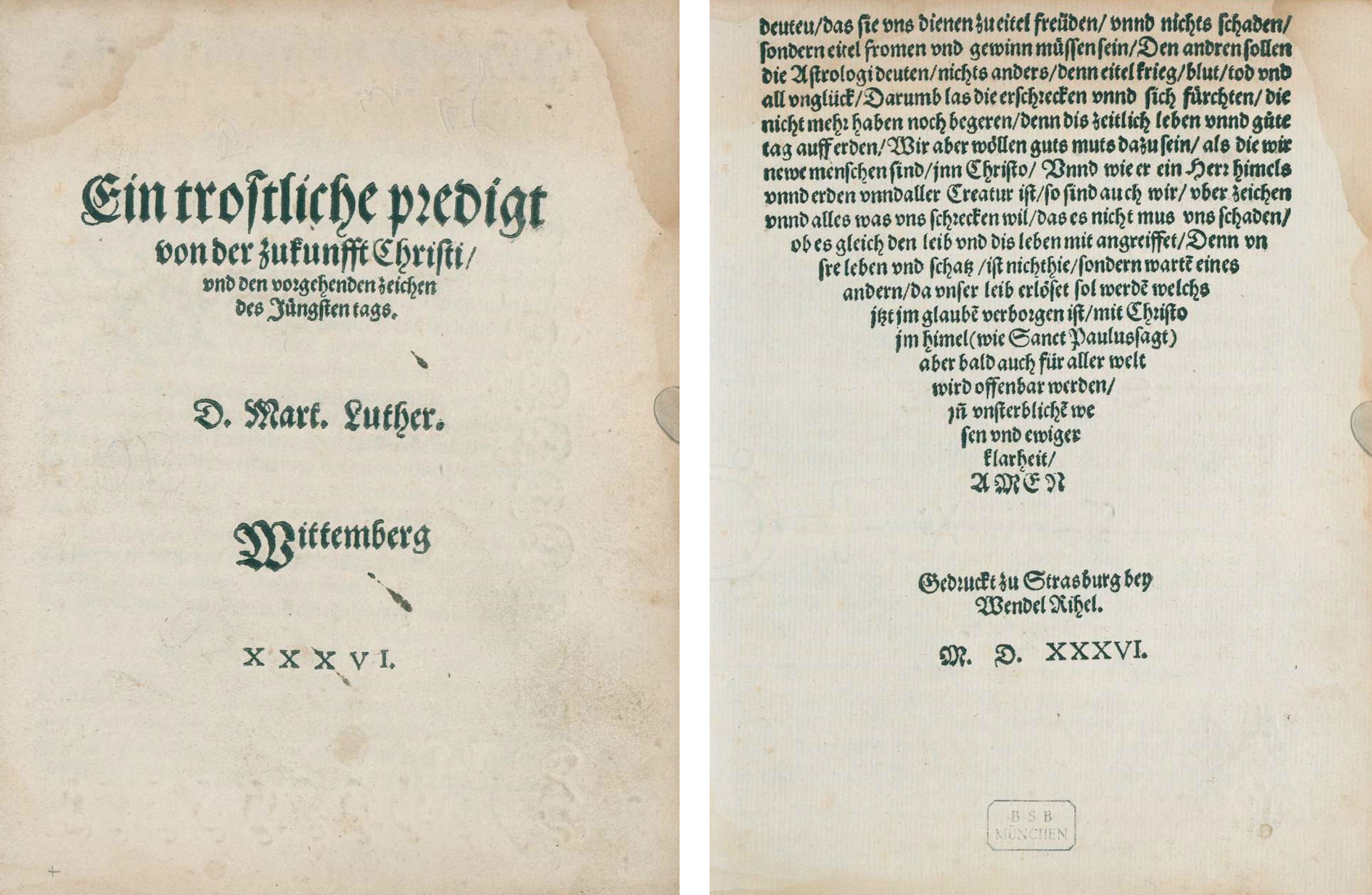

A perfect example is a 1536 edition by the Strasbourg printer Wendelin Rihel.11 The text is a sermon originally printed in Wittenberg by Joseph Klug.12 It has a simple title page with the title arranged in a half diamond, with decreasing centre alignment and the first line in a larger typeface (Figure 15.3). Luther, separated from the title, is identified as the author. ‘Wittenberg’ is listed below, followed by the date. The ‘W’ in ‘Wittenberg’ is from the large typeface used on the first line of the title. It is the largest typeface used on the page, larger than the type used to identify Luther. ‘Wittenberg’ is inserted on the lower part of the page, and combined with the large initial letter, stands out on the page. In fact, the spacing between the title, author, and city follows the layout of the original Wittenberg edition. While the printer was clearly implying this work was from Wittenberg, there is a full colophon with the real city, printer and year. (Figure 15.3).

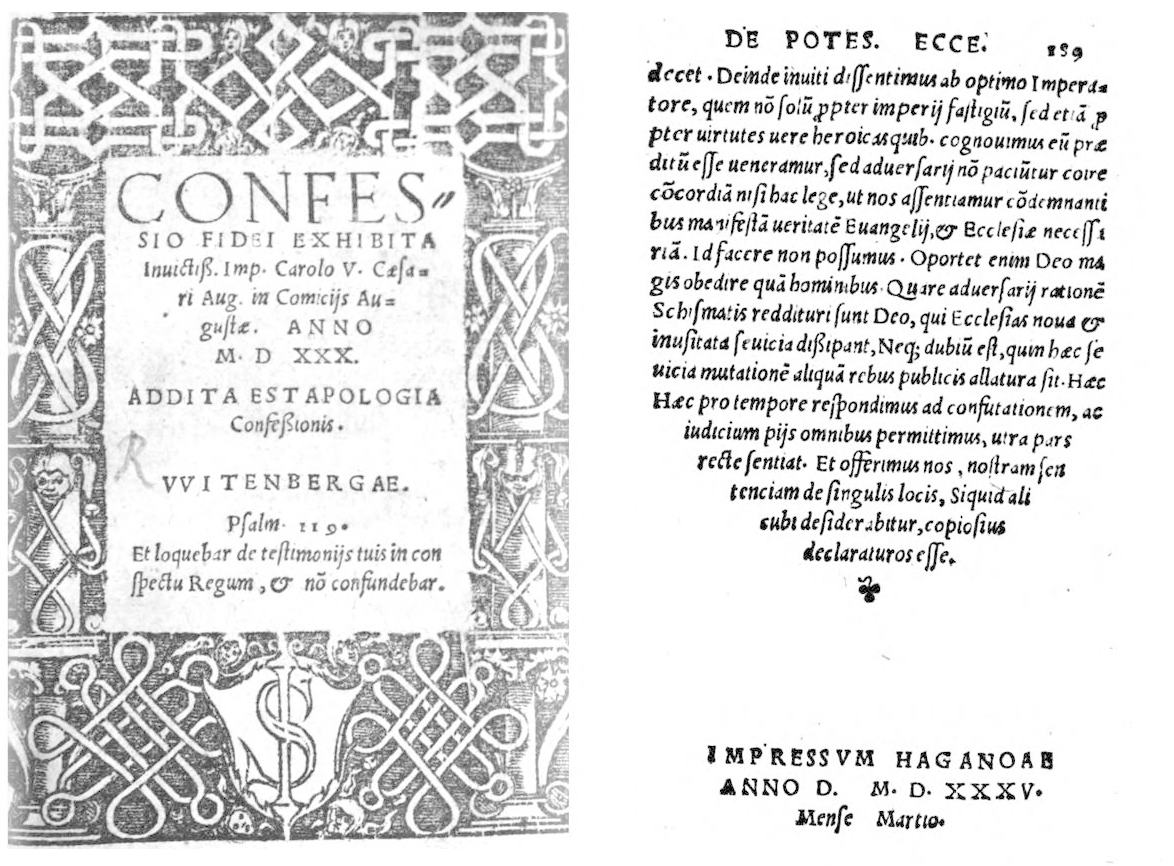

In 1535 Peter Braubach of Haguenau printed a copy of the Augsburg Confession, which was first presented to Emperor Charles V at the imperial Diet in 1530.13 Braubach used a single piece title page border and lists ‘Wittenberg’ in capital letters at the bottom of the title page, above a verse from Psalm 119 (Figure 15.4). However, Haguenau is listed in the colophon as the real city of publication: ‘IMPRESSVM HAGANOAE ANNO D. M.D.XXXV. Mense Martio’.

In the first example Rihel used a false Wittenberg imprint, but identified himself as a Strasbourg printer in the colophon. It is odd that he identifies himself while knowingly using a false imprint. Perhaps he would argue that it does not say ‘printed in Wittenberg’ and that he simply meant the sermon was preached in Wittenberg. Regardless, in both examples, Wittenberg is the only city on the title page. A broader examination of Rihel’s and Braubach’s output reveal that both printers often adopted full, accurate imprints on the title page of their editions. The fact that they varied their usual practice in these examples indicates a clear intention to deceive prospective buyers.

Simple Counterfeits

This category encompasses works that are fully counterfeit. There is no ambiguity as in the previous categories. These are works that have a false Wittenberg imprint and no city listed in the colophon. They are by far the most numerous, with hundreds of examples, and were clearly meant to deceive. They often followed the line breaks of the title on the original Wittenberg edition. In one case, they even preserved an error in the Roman numeral date of the Wittenberg edition. This suggests that the compositor was copying the Wittenberg edition without noticing the mistake, possibly under explicit instruction of closely reproducing the model.

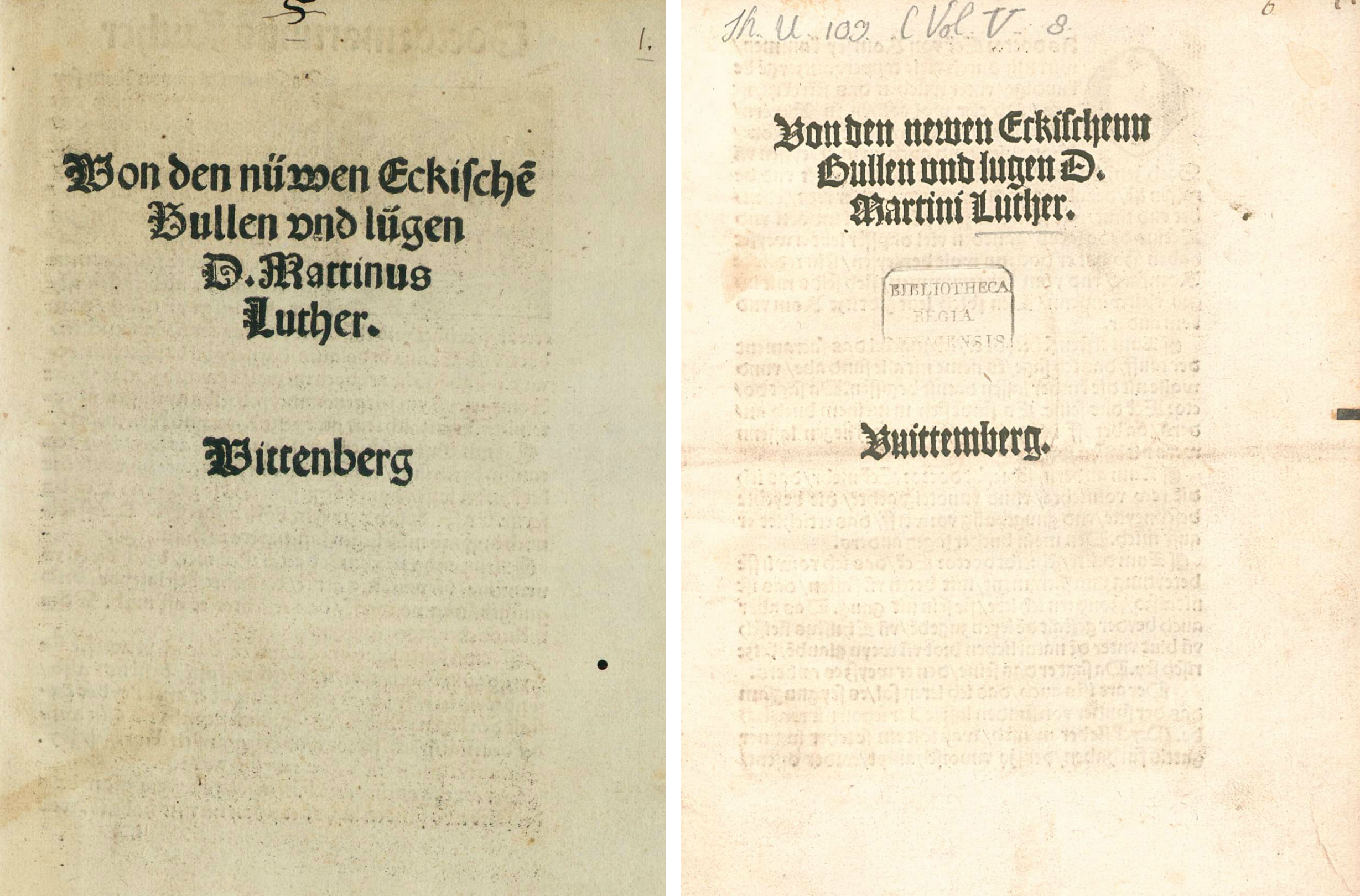

An early example is a short pamphlet by Luther against Johann Eck, printed in 1520 in Basel by Adam Petri.14 It is a very simple title page with only one typeface. The wide spacing and decreasing centre alignment of the title, which directs the eye, puts all the focus on ‘Wittenberg’. The layout is like the original Wittenberg edition by Melchior Lotter, but has different line breaks (Figure 15.5).15 The two editions also have the same paragraph breaks and only list the year in the colophon.

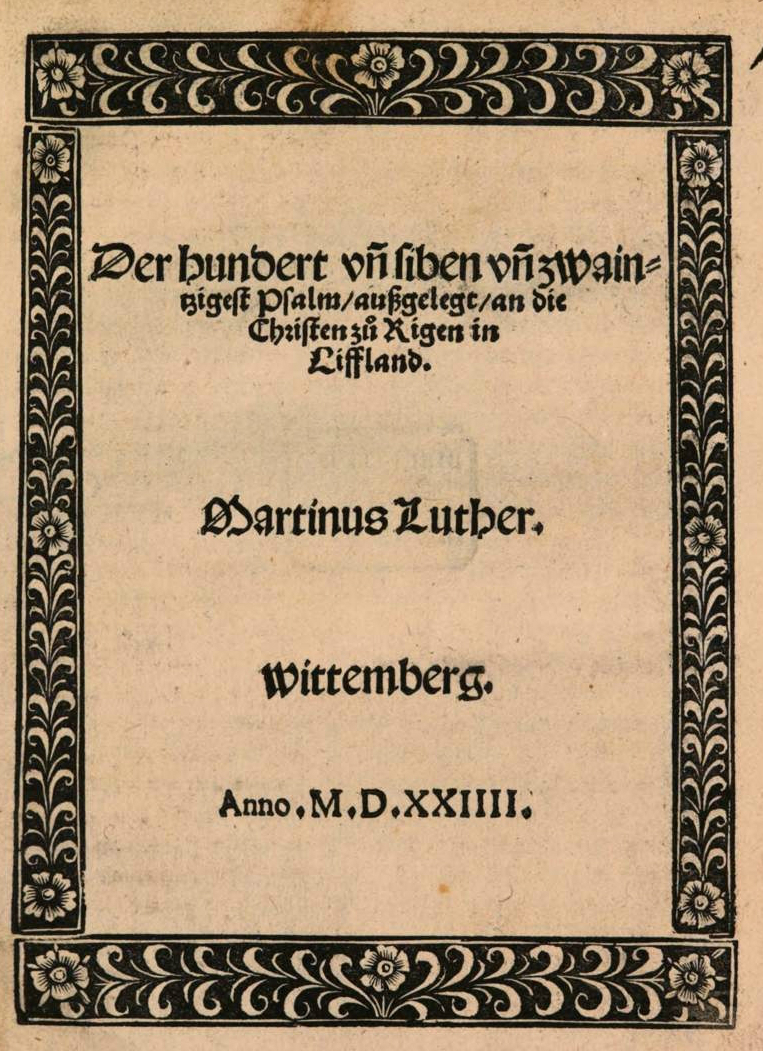

In 1524, the Augsburg printer Silvan Otmar printed a copy of Luther’s work on Psalm 127 (Figure 15.6).16 Following the title is Luther’s name and an imprint with the city and year. There is very good spacing between each item and Luther’s name is a separate line. Both Luther’s name and the imprint are in the larger typeface. There is also a four-piece, floriated, woodcut title page border. Otmar actually produced two different editions of this counterfeit in 1524. There was also another counterfeit edition produced in Constance.17

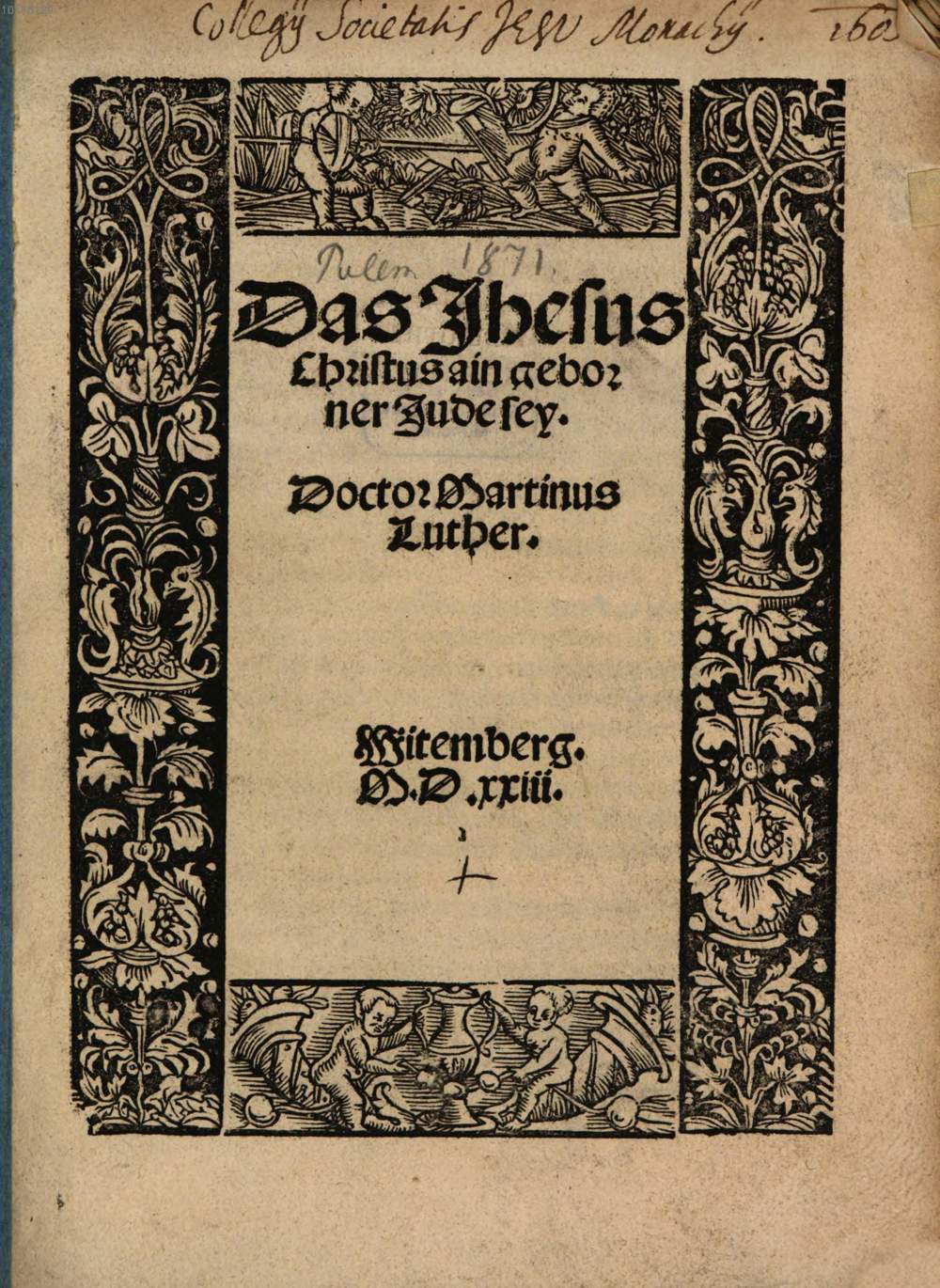

A further example of a simple counterfeit is an Augsburg edition of Luther’s That Jesus Christ Was Born a Jew, printed in 1523 by Melchior Ramminger (Figure 15.7).18 It also has a four-piece woodcut title page border. Like the previous example, Luther’s name is separated from the title. However, this time ‘Wittenberg’ is located directly above the year. Here there is no doubt ‘Wittenberg’ is part of the imprint. The work must have been popular, as Ramminger produced three counterfeit editions in 1523.

Wittenberg counterfeits such as these were produced quickly and on a wide scale. As the examples show, unlike the previous categories, they were deliberately produced to deceive. Readers thought they were buying works from Wittenberg, the source for Reformation news and Luther’s writings. While many of these works were easy to reproduce, the final category focuses on works that required more time and a more advanced design.

Advanced Counterfeits

In addition to copying the title page design, advanced counterfeits also copied the woodcut title page borders from Wittenberg editions. The famed Renaissance artist Lucas Cranach the Elder was the court painter to the Elector of Saxony, Frederick the Wise. His workshop in Wittenberg supplied many woodcuts to local printers, most notably his woodcut illustrations in the 1522 edition of Luther’s New Testament translation.19 His title page borders featured prominently on many Reformation pamphlets and helped elevate the quality and status of Wittenberg print.20 Many printers in other cities copied his borders, but usually at an inferior quality. These counterfeits required more skill and a greater investment by the printer, and consequently, more time. Thus, they were rarer. Nonetheless, over fifty counterfeits have been so far identified where printers copied Wittenberg title page borders.

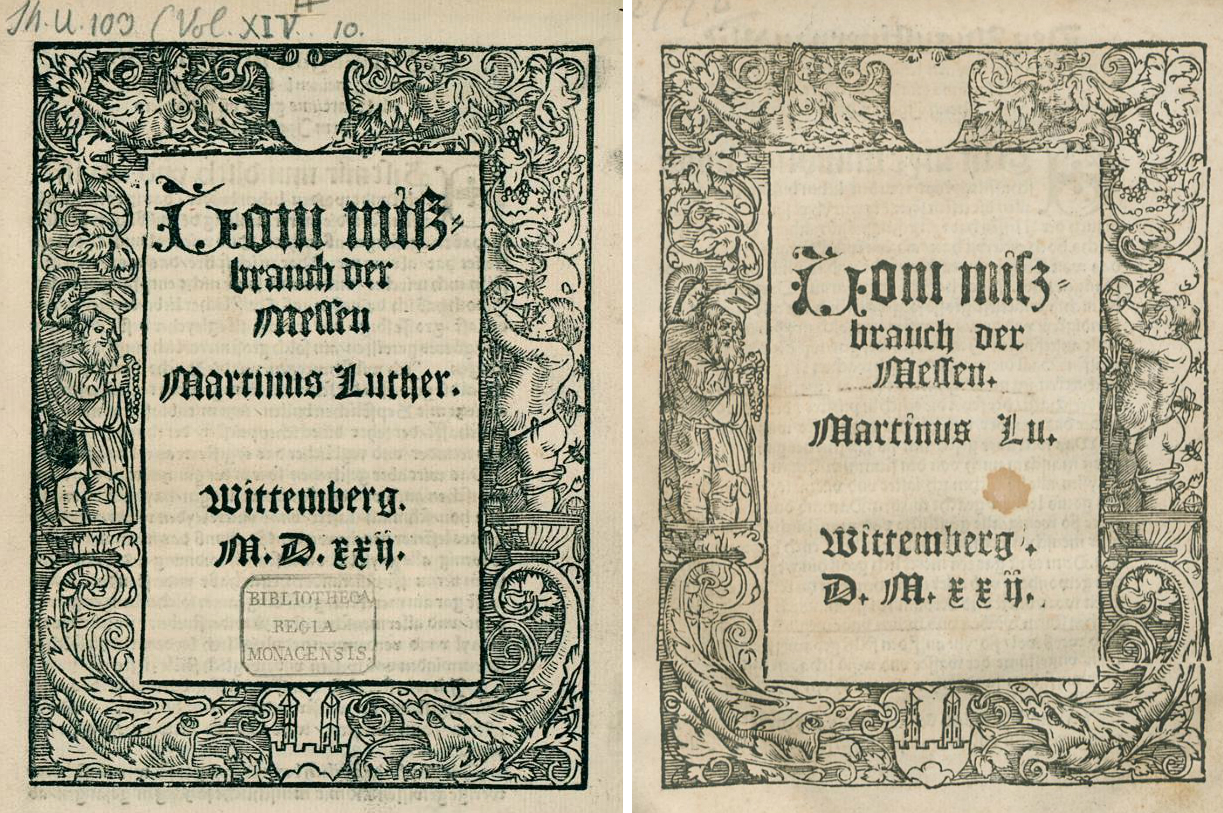

An early example is a 1522 edition of Luther’s The Misuse of the Mass, printed by Heinrich Steiner in Augsburg (Figure 15.8). Steiner printed two editions that year, which have identical title pages.21 Luther’s name is in the middle of the page and the imprint is at the bottom. The line breaks in the title are identical to the original Wittenberg edition (Figure 15.8).22 Both also include imprints with the city and year. The Wittenberg edition has an error in the dating, which is corrected in the Augsburg edition. Also, the Wittenberg edition abbreviates ‘Luther’ as ‘Lu.’ The Augsburg edition spells Luther’s name out in full.

The most interesting aspect is that Steiner copied the Cranach woodcut title page border from the Wittenberg edition. The two borders are nearly identical; however, there are differences in the shading in the man’s clothing on the right and the man’s moneybag on the left. Another interesting aspect of this counterfeit is the ornate initial used at the beginning of the title. This is unusual as ornate initials were generally reserved for the text, not the title page. However, Steiner even copied this initial, though there are slight differences.

Intricate title page borders were not cheap. They added to the production costs and the amount of time needed to reproduce a Wittenberg edition. In order to recuperate the cost, printers would reuse the title page borders in multiple editions. One such example was a Luther pamphlet on the sacraments. It was printed in 1524 by Hieronymus Höltzel in Nuremberg (Figure 15.9).23 Höltzel printed a false Wittenberg imprint and used a copy of a Cranach title page border. The border has a small area for text and features two lions prominently in the bottom corners. This is a title page used in many Wittenberg editions.

This example also reveals copying practices within the print shop. In the Nuremberg copy, the lions are in the opposite corners from the Wittenberg border. The artist copied the woodcut as it appeared in the printed Wittenberg edition. Thus, since woodcuts are carved in relief, his copy was reversed when inked and pressed against a new sheet of paper. Given more time, an artist could produce a correctly oriented copy, such as the previous example, but the method used in this example was a quicker process. Printers also used copies of Cranach’s borders in non-counterfeit editions. This allowed printers to recuperate their investment over multiple editions. It is also a testament to the effectiveness of Wittenberg design and its ability to influence other printers. However, the counterfeits did not go unnoticed in Wittenberg. The solution was to develop methods to combat the competition.

Combatting Counterfeits

In 1524, the Saxon Elector granted Luther a coat of arms decorated with a cross in the middle of a white rose, flanked by Luther’s initials on either side.24 This symbol became a seal used on Luther’s works printed in Wittenberg to prove their authenticity (Figure 15.10). In one edition, Luther notified readers and warned other printers to “Let this symbol be proof that these books have passed through my hands, for many are today engaged in falsifying publications and ruining books.”25

But this emblem was not a guarantee of authenticity. It too was soon copied. That same year the border was copied by Philip Ulhart in Augsburg. But there was one major difference. Ulhart copied the Cranach title page border, including Luther’s initials, but did not reproduce the white rose (Figure 15.11). Instead, he inserted a blank shield.26 It is odd that he went to the trouble of reproducing the entire border, but not the rose, especially given the fact that he also used another title page border that did include the rose (Figure 15.11). Although the architectural border is slightly different and Luther’s initials are missing, the resemblance to Luther’s white rose is indisputable.

The Nuremberg printer Jobst Gutknecht also copied Luther’s white rose. However, he also incorporated the Saxon Electoral shield – the sign of Luther’s protector – into his border(Figure 15.12).27 Thus, while Wittenberg printers attempted to combat the unusual competition they faced from counterfeiters, the counterfeiters quickly adapted. There was little Wittenberg printers could do, as counterfeits were produced all over Europe.

Geographic Distribution of Counterfeits

Every major printing centre in the Holy Roman Empire produced counterfeit Wittenberg editions. A vast majority – nearly 70% – were produced between 1520 and 1525. This coincided with Luther’s most active years.28 But counterfeiting was not limited to the imperial realm. They were also produced in England, France, the Low Countries, Poland, and the Swiss Confederation, 33 cities in all. The bulk of the false Wittenbergs, however, came from three cities: Augsburg, Erfurt, and Nuremberg. Together they account for nearly 60% of all Wittenberg counterfeits (Figure 15.13).

Augsburg produced more counterfeit editions than any other city, approximately 150 editions. A Free Imperial City located in Bavaria, Augsburg was home to the important Fuggar and Welser banking families, and one of the centres of international trade. Due to the concentration of such wealth in the city, there was plenty of capital to support a vibrant print industry.29 Ten different printers manufactured counterfeit editions. Augsburg’s three largest printers, Heinrich Steiner, Melchior Ramminger and Jörg Nadler, were among the top Wittenberg counterfeiters in all of Europe.

Erfurt, located southwest of Leipzig, was where Luther went to university and joined the Augustinian order in 1505. During his lifetime, Erfurt printers produced over one hundred Wittenberg counterfeits. Erfurt’s counterfeits were more evenly split among four printers: Johann Loersfeld, Matthes Maler, Wolfgang Stürmer, and Melchior Sachse. Nearly two-thirds of Luther’s works printed by Loersfeld were counterfeits. For Maler, one in every three Luther works was a counterfeit. Surprisingly, there are only two instances of copied title page borders in Erfurt. Copying a Cranach border would have taken more time to execute. Since Erfurt was the closest city to Wittenberg among the top counterfeiting centres, they needed to reproduce Luther’s works quickly before the Wittenberg editions flooded their own regional market.

Nuremberg publishers were responsible for approximately a hundred Wittenberg counterfeits. Although the Nuremberg printer Jobst Gutknecht was the largest counterfeiter in the city and one of the top in Europe, counterfeit editions in Nuremberg were much more evenly divided among thirteen printers. Hieronymus Höltzel was one of four printers in the city that produced advanced Wittenberg counterfeits. He copied the Cranach title page border with the two lions and made frequent use of it.30 It was not uncommon for printers to use copies of Cranach’s title page borders even if the original Wittenberg edition did not.

In the thirty-three places where Wittenberg editions were counterfeited, over seventy printers produced counterfeit Wittenberg editions. Clearly it was not a niche market confined to a single printer within a locality; rather, it was a widespread practice. And for a few printers, counterfeiting was extremely lucrative making up a large percentage of the Reformation works they printed. The Imperial cities had a particular advantage, in that not being part of an ecclesial or princely territory, they were outside the jurisdiction of other printer’s privileges or bans instituted by anti-Lutheran princes or bishops. Nuremberg did pass a ban against Luther’s works, but the city council turned a blind eye to the practice.31

In any case, the items printers counterfeited were unlikely to have a privilege because of their short length. A significant number of the counterfeits required only four sheets of paper or less per copy, meaning it was not a large investment. Printers mostly sought privileges to minimise risk for larger works that had higher production costs. For example the Saxon Elector John the Steadfast issued a privilege to the Wittenberg publishers Lucas Cranach and Christian Döring for the Old and New Testaments.32 Those works required a far larger investment and a privilege protected their profits.

Most of the items counterfeited were short works such as Luther’s sermons, commentaries, and polemical tracts. Luther excelled at this genre. They were cheap to produce and easy to counterfeit for these same reasons. Many counterfeiters specifically focused on these shorter works. This practice may indeed have been more widespread than is evidenced in this essay. Short pamphlets were ephemeral by nature, often distributed unbound. Thus, their survival rates are much lower.

Many counterfeits might also be ‘hiding’ behind catalogue descriptions. Differences between true and false Wittenberg imprints are, as demonstrated here through various examples, often almost imperceptible. In many cases, even a diplomatic title page transcription would not be able to highlight them. For the present work, I systematically investigated all of Luther’s works printed before 1550 in the leading German print centres. I intend to continue my investigation by examining multiple copies of the same edition, which is likely to turn in even more counterfeits yet uncovered.

Counterfeiting Wittenberg books was not confined to the Empire. More than two dozen editions were produced abroad in England, France, the Low Countries, Poland, and the Swiss Confederation. Most interesting are the editions printed in Paris and London. The Paris editions were printed in 1521 at a period when scholars were still curious about Luther and his ideas. They were all printed in Latin, which is expected, as Paris would not have been the market for Luther’s vernacular pamphlets. Scholars at the University of Paris were curious about Luther’s ideas and were selected to provide an official response to the Leipzig Debate between Luther and Johannes Eck in 1519. In the end, they refrained from issuing a public response. The London editions, however, were not printed in Latin; they were printed in English and much later in 1547. While the Paris editions were likely counterfeit to avoid local bans on printing such documents, the London imprints must have been intended satirically, as there was no English printing in Wittenberg. Regardless, both instances raise interesting questions about the ability of Luther’s works to travel across international borders. When compared to other contemporary, high profile authors, such as Erasmus of Rotterdam, Luther’s works were generally confined to German speaking lands due to his practice of writing in the vernacular.33 Erasmus wrote mostly in Latin, facilitating international exchange. The large amount and vast reach of Wittenberg counterfeits provide a unique insight into the geographical distribution of works printed in Wittenberg. While surviving bookseller catalogues or estate inventories offer individual instances of an edition’s distribution patterns, mapping counterfeit production exposes larger distribution networks. This is based on the fact that the counterfeiter had to possess a Wittenberg copy in hand to produce an accurate counterfeit, for example with identical title page line breaks. Cheap counterfeits thus also demonstrates the reach of authentic Wittenberg editions.

Cashing in on Counterfeits: Incorporating Wittenberg into Marketing Strategies

The counterfeiting of Wittenberg editions was not the first instance of false information on title pages. False imprints were not a new phenomenon. They were as old as the innovation of the title page in the third quarter of the fifteenth century. Publication information, usually reserved for the colophon at the end of the book, slowly made its way to the title page in the form of an imprint.34 Early sixteenth-century books often had both an imprint and a colophon. A book might list the city and year of publication in the imprint on the title page and list the printer in the colophon. These three important pieces of information – city, printer, and year – were arranged in a number of combinations, often inconsistently in works by the same printer.

Colophons appeared regularly in books from 1457 onwards.35 Even though they were developed to identify the details of publication, a large number contained incorrect information. While in many instances the incorrect information was deliberate, the majority of cases were accidental.36 Most were simply errors in dating, such as MCDLXIX (1469) instead of MCDLXXI (1471). Curt Bühler documents many such instances and claims printers were indifferent to the accuracy of the date.37 This discussion however is not concerned with false imprints that were accidental. Rather, it concentrates on places of publication – in this case, Wittenberg – that have been deliberately falsified in the imprint.

There were many reasons why a printer would lie about the place of publication. Printers often sought privileges for their works from local authorities, which legally guaranteed a monopoly for a particular title. Another printer might print an unauthorized copy, but change the imprint so that the work appeared to originate from outside the jurisdiction of the privilege. For example in 1499 the Italian printer Bernardinus de Misintis printed a copy of Politian’s Opera in Brescia, but listed Florence in the colophon.38 As Brescia was within the jurisdiction of Venice, Bernardinus was attempting to conceal his violation of a privilege granted to the famed printer Aldus Manutius. Aldus was not fooled and complained to the Venetian senate.39

A similar example is that of the Italian printer Lorenzo de’ Rossi who listed Venice as the place of publication on some of his works even though they were printed in Ferrara. He was not copying other editions, but thought placing Venice on the title page would make it more attractive in a local Venetian market.40 Also, in Lyon Jacobinus Suigus and Nicholas de Benedictus falsified Bolognese and Venetian imprints. But none of these were on the scale of the false Wittenberg editions.

Another reason printers would dissemble about the place of publication was to circumvent local prohibitions on printing certain books. The more restrictions and interference imposed by authorities, the more likely printers would resort to deception.41 If a work was on a list of banned books, a printer would use a false imprint to disguise his involvement in the project.42 Such was the case in Leipzig, the largest printing centre in the Holy Roman Empire at the beginning of the Reformation. Leipzig was a center of trade in ducal Saxony, which remained Catholic until the death of the Saxon Duke George in 1539. Leipzig printers were forbidden from printing Luther’s works, much to their dissatisfaction and the detriment of their industry.43 They felt disadvantaged that they were prohibited from printing items that would sell quickly and guarantee a profit. This did not stop them however. Michael Bloom was an active printer in Leipzig during the Reformation and he printed multiple works with ‘Wittenberg’ listed in the imprint. One such edition was the Admonition to Peace described at the beginning of this essay.

While circumventing privileges and local bans were good reasons to lie about the place of publication, by far the most popular reason to print a fake Wittenberg imprint was to increase its marketability. People wanted news from Wittenberg. And Luther satisfied this demand, writing tract after tract. Readers were assured of a text’s authenticity and accuracy if it was from Wittenberg.

Luther was well aware of unauthorised editions of his works. In the preface of the Exposition of the Epistles and the Gospels from the Nativity to Easter in 1525, he chastised printers who made unauthorised copies of his works.44 He complained about the inferior quality and errors in counterfeit editions, claiming they were so full of errors that he was forced to renounce them as his own work. While Luther was of course concerned about the accuracy of his texts, he was also looking out for the interests of Wittenberg printers, many of whom were his friends.

The case of Wittenberg is unique because it is the first instance of a place of publication being the target of such widespread fraud. Usually printers and authors, not cities, were the subjects of fraud. Aldus Manutius is probably the best-known example of a printer being the target of counterfeits. Printers in Lyon went to such extraordinary lengths to produce counterfeit Aldus editions that they even copied his italic type.45 In terms of authors, Erasmus was probably the most prolific author, along with Luther, to be the subject of counterfeiting. In fact, it was Johann Froben’s unauthorized edition of an Erasmus work printed by Aldus that attracted Erasmus to Basel.46

In the case of false Wittenberg imprints, printers were using the imprint as a marketing tool to promote their editions. Instead of the imprint simply providing the details of publication, it was incorporated into printers’ larger marketing strategies. In this sense, Wittenberg was becoming a brand to be copied. In addition to the Wittenberg imprint, the layout and title page borders were also copied. Over fifty of the counterfeit editions were by authors other than Luther. When an author’s name did not carry the same recognition that Luther’s did, a false Wittenberg imprint helped the reader to associate the work immediately with the Reformation movement.

“They have also learnt the trick of printing Wittenberg upon some books which never appeared at Wittenberg at all!”.47 Luther was very aware that false Wittenberg imprints were in use during the Reformation. Over seventy printers in numerous cities produced more than five hundred counterfeits of Wittenberg editions. They incorporated the imprint, usually reserved for publication information, into their marketing strategies, knowing it would increase their market appeal. This was not reserved for Luther’s texts alone, but used with the works of other reformers as well. Furthermore, it was not the work of lone printers, as multiple, prominent printers in the same cities produced Wittenberg counterfeits at the same time. If anything, this essay has shown that producing Wittenberg counterfeits was not an anomaly within the industry, but rather a common occurrence and widely practiced. The print industry played a large role in the success of the Protestant Reformation. It is now clear, fraud was an important tool in that success.

Luther recalls this in the preface of Auslegunge der Episteln und Evangelien von der heyligen drey Koenige fest bis auff Ostern gebessert (Wittenberg: Melchior II Lotter for Lukas Cranach & Christian Döring, 1525). USTC 613951.↩︎

The three Wittenberg editions, all by Joseph Klug, are USTC 653523, 653524, and 653525.↩︎

Figures from the USTC.↩︎

George Frederick Barwick, ‘The Lutheran Press at Wittenberg’, Transactions of the Bibliographical Society, 3 (1896), pp. 9-25: 10.↩︎

Hans-Jörg Künast, Getruckt zu Augsburg: Buchdruck und Buchhandel in Augsburg zwischen 1468 und 1555 (Tübingen: Niemeyer, 1997) pp. 167-68.↩︎

However, while outside the scope of this research, even works with an imprint stating another city, but also using Wittenberg in the title, are still trying to associate the work with Wittenberg.↩︎

Martin Luther, Ain sermon von dem bann (Augsburg: Silvan Otmar, 1520), USTC 610282. Bibliothèque de la société de lhistoire du protestantisme français, 4° 1317 Rés.↩︎

Martin Luther, Ein sermon von dem bann (Nuremberg: Jobst Gutknecht, 1520), USTC 647046. Bibliothèque de la société de lhistoire du protestantisme français, 4° 1318 Rés.↩︎

Martin Luther, Ain sermon von dem gebett unnd procession. In der Creützwochen. Mit einer kurtzen Außlegung des vatter unnsers für sich und hinter sich oratio dominica dicitur et oratur duplici via recta et versa (Augsburg: Hans Froschauer, 1519), USTC 610357. Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, 4 Hom. 1185 <http://www.mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn/resolver.pl?urn=urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb10161421-5> (last accessed 9 December 2017).↩︎

Barwick, ‘The Lutheran Press at Wittenberg’, p. 10.↩︎

Martin Luther, Ein trostliche predigt von der zukunfft Christi und den vorgehenden zeichen des juengsten tags (Strasbourg: Wendelin I Rihel, 1536), USTC 647263. Bibliothèque de la société de lhistoire du protestantisme français, 4° 1391 Rés.↩︎

The original Wittenberg edition by Klug is USTC 647219. Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Sachsen-Anhalt, Pon Vg 2425, QK.↩︎

Confessio fidei exhibita invictiß. Imp. Carolo V. Caesari aug. In comiciis augustae. Anno M.d XXX. Addita est apologia confeßionis (Haguenau: Peter Braubach, 1535), USTC 624444. Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, H.ref. 92 <http://www.mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn/resolver.pl?urn=urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb10179007-8> (last accessed 9 December 2017).↩︎

Martin Luther, Von den nüwen Eckischen bullen und lügen (Wittenberg [=Basel]: Adam Petri, 1520), USTC 703267. Bibliothèque de la société de lhistoire du protestantisme français, 4° 1324 Rés.↩︎

The Wittenberg edition by Lotter is USTC 703265. National Library of Scotland, Crawford. R. 203.↩︎

Martin Luther, Der hundert und siben und zwaintzigest psalm (Wittenberg [=Augsburg]: Silvan Otmar, 1524), USTC 633613. Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, 4 Exeg. 484 <http://www.mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn/resolver.pl?urn=urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb10159313-8> (last accessed 9 December 2017).↩︎

The other Augsburg edition is USTC 633614. The Constance edition is USTC 633626.↩︎

Martin Luther, Das Jhesus Christus ain geborner Jude sey (Wittenberg [=Augsburg]: Melchior Ramminger, 1523), USTC 627551. Bibliothèque de la société de lhistoire du protestantisme français, 4° 1360 Rés.↩︎

Martin Luther, trans. Das Newe Testament (Wittenberg: Melchior II Lotter for Lucas Cranach & Christian Döring, 1522), USTC 627911. Forschungsbibliothek Gotha, Theol 2° 00035/01.↩︎

See Andrew Pettegree, Brand Luther: 1517, Printing and the Making of the Reformation (New York: Penguin Press, 2015) pp. 158-63.↩︎

Martin Luther, Vom mißbrauch der Messen (Wittenberg [=Augsburg]: Heinrich Steiner, 1522), USTC 641123 and 700033. Bibliothèque de la société de lhistoire du protestantisme français, 4° 1361 Rés. and Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Res/4 Th.u. 103,XIV,10 <http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/bsb00028966/image_1> (last accessed 9 December 2017).↩︎

Martin Luther, Vom miszbrauch der Messen (Wittenberg: Johann Rhau-Grunenberg, 1522), USTC 700034. Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Sachsen-Anhalt, Ib 3676 a (4) <http://digitale.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/vd16/content/titleinfo/999670> (last accessed 9 December 2017).↩︎

Martin Luther, Von der frucht und nutzparkayt des heyligen Sacraments (Wittenberg [=Nürnberg]: Hieronymus Höltzel, 1524), USTC 700131. Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Res/4 Th.u. 103,XXVI,23 a <http://reader.digitale-sammlungen.de/resolve/display/bsb10204485.html> (last accessed 9 December 2017).↩︎

Steven Ozment, The Serpent & the Lamb: Cranach, Luther, and the Making of the Reformation (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011), p. 112.↩︎

Ibid., p. 113.↩︎

Martin Luther, Wider den neuwen Abgott und allten Teuffel der zu Meyssen soll erhaben werden (Wittenberg [=Augsburg]: Philipp I Ulhart, 1524), USTC 706627. Bibliothèque de la société de lhistoire du protestantisme français, 4° 1378 Rés.↩︎

Martin Luther, Eyn kurtze unterrichtug warauff Christus seine Kirchen oder gemain gebawet hab (Wittenberg [=Nürnberg]: Jobst Gutknecht, 1524), USTC 656115. Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Res/4 Polem. 3365,17 <http://www.mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn/resolver.pl?urn=urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb10204013-0> (last accessed on 9 December 2017).↩︎

The figures in this section only include editions that have a false Wittenberg imprint. Only items from the last three categories discussed (False by Implication, Simple Counterfeits, and Advanced Counterfeits) are included, as the items in the first category are not truly fraudulent.↩︎

For a detailed analysis of the Augsburg industry, consult Künast’s Getruckt zu Augsburg. See note 5.↩︎

For an example of Höltzel’s copy of Cranach’s title page border see USTC 627386. Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Res/4 Th.u. 103,IX,1.↩︎

Pettegree, Brand Luther, 220.↩︎

John L. Flood, ‘Lucas Cranach as Publisher’, Life & Letters, 48 (1995), pp. 241-262: 243.↩︎

According to the USTC, for the sixteenth century there were 3,770 Luther editions printed in German. There were only 705 printed in Latin.↩︎

See Margaret M. Smith, The Title-Page: Its early development, 1450-1510 (London: The British Library & Oak Knoll Press, 2000).↩︎

Curt F. Bühler, ‘False Information in the Colophons of Incunabula’, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 114.5 (1970), pp. 398-406: 398.↩︎

Bühler, ‘False Information’, pp. 398-399.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

The colophon of the edition reads: “Impressum Florentiae: & accuratissime castigatum op[er]a & impensa Leonardi de Arigis de Gesoriaco Die decimo augusti .M.ID.” (USTC 991841, copy at Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek (2 Inc.c.a. 3798 n), consulted digitally via the Münchener DigitalisierungsZentrum).↩︎

Bühler, ‘False Information’, p. 401. The document has been digitized by the Archivio di Stato in Venice on the occasion of the 500th anniversary celebrations of Aldus’s death in 2015, and is freely accessible online at <http://www.archiviodistatovenezia.it> (last accessed on 5 November 2017). The original text reads: “Et p[er]che li vengono tolte le sue fatiche, et guasto quello che lui conza, come e stato facto in bressa, che hano stampato una de sue opere, et falsato: dicendo Impressum Florentiae”: “and as his efforts are taken away from him, and what he creates is ruined, as it was done in Brescia, that they printed one of his works falsely, saying Printed in Florence”. Venice, Archivio di Stato, Senato, Deliberazioni, Terra, reg. 14, c. 112r. 17 October 1502, Conferma decennale dal Senato dei privilegi concessi ad Aldo Manuzio per i caratteri greci e corsivi e contro le contraffazioni delle sue edizioni. Thank you to Dr Shanti Graheli for the translation.↩︎

Bühler, ‘False Information in the Colophons of Incunabula,’ p. 401.↩︎

Lotte Hellinga, ‘Less than the Whole Truth: False Statements in 15th-Century Colophons’, in Robin Myers and Michael Harris (eds.), Fakes and Frauds: Varieties of Deception in Print & Manuscript (New Castle, DE, and Winchester: Oak Knoll Press and St. Paul’s Bibliographies, 1989), pp. 1-27: 5.↩︎

Michael Treadwell, ‘On False and Misleading Imprints in the London Book Trade, 1660-1750’, in Myers and Harris (eds.), Fakes and Frauds, pp. 29-46: 32.↩︎

For more on the collapse of the Leipzig industry, see Drew Thomas, ‘Circumventing Censorship: The Rise and Fall of Reformation Print Cities’, in Alexander Wilkinson and Graeme Kemp (eds.), Conflict and Controversy (Leiden: Brill, forthcoming).↩︎

Martin Luther, Auslegunge der Episteln und Evangelien von der heyligen drey Koenige fest bis auff Ostern gebessert (Wittenberg: Melchior II Lotter for Lukas I Cranach & Christian Döring, 1525), USTC 613951.↩︎

David J. Shaw, ‘The Lyons counterfeit of Aldus’s italic type: a new chronology’, in Denis V. Reidy (ed.), The Italian Book 1465-1800: Studies Presented to Dennis E. Rhodes on his 70th Birthday (London: The British Library, 1993), pp. 117-133.↩︎

Eileen Bloch, ‘Erasmus and the Froben Press: The Making of an Editor’, The Library Quarterly 35.2 (April 1965), pp. 109-120: 109. Also see, Percy Stafford Allen, ‘Erasmus’ Relations with his Printers’, The Library, 13.1 (1913), pp. 297-322.↩︎

In the preface of Auslegunge der Episteln und Evangelien von der heyligen drey Koenige fest bis auff Ostern gebessert (Wittenberg: Lukas Cranach & Christian Döring, 1525), USTC 613951.↩︎