A Crowded Field in Luther’s Wittenberg:

Collaboration and Sub-Contracting in the Reformation Book Trade

This article examines the overlooked printers in Martin Luther’s Wittenberg during the Protestant Reformation, who contributed to the town’s emergence as a major printing center. While renowned printers like Johann Rhau-Grunenberg and Melchior Lotter the Younger have been extensively studied, this research focuses on the smaller printers who operated between 1525 and 1550. Divided into two groups—those who relocated and those who persisted after Luther’s death—they maintained active relationships with larger printing houses. By tracing the reuse of woodblocks, it is revealed that these minor printers were integrated into Wittenberg’s printing network, shedding light on their significance in the industry.

Notice: This document is a post-peer review author approved manuscript of Drew B. Thomas, “A Crowded Field in Luther’s Wittenberg: Collaboration and Sub-Contracting in the Reformation Book Trade” in Arthur der Weduwen and Malcolm Walsby (eds.), The Book World of Early Modern Europe: Essays in Honour of Andrew Pettegree, Volume 2 (Leiden: Brill, 2022), pp. 36-50. It has been typeset by the author and is for informational purposes only. It is not intended for citation in scholarly work and may differ in content and form from the final published version. Please refer to and cite the final published version, accessible via its DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004518100_005.

Martin Luther’s Protestant Reformation ushered in a wave of printing activity across the Holy Roman Empire. Not only did established printing houses expand during the period, new workshops in towns on the periphery of the printing scene also sprang up. Nowhere was this truer than in Luther’s residence of Wittenberg. When Luther wrote his Ninety-Five Theses in 1517, there was only one commercial printer in the town. By his death nearly thirty years later, at least eighteen printers vied for a slice of the market in Wittenberg. Some were rewarded handsomely for their work; others quickly cut their losses and moved elsewhere. This chapter investigates the lesser-known printers operating in Wittenberg, often overshadowed by their more successful peers, and examines the role they played in helping the town become one of the largest print centres in early modern Europe.

At the beginning of Luther’s evangelical movement, Johann Rhau-Grunenberg and Melchior Lotter the Younger were the two main printers of Wittenberg.1 It was Lotter who printed Luther’s famous German translation of the New Testament in 1522.2 They were followed by Josef Klug, Hans Lufft, Georg Rhau and Nickel Shirlentz – the only printers who were active in Wittenberg continuously from the 1520s through Luther’s death in 1546. The successful careers of these printers has been explored elsewhere.3 In this chapter I will instead focus on the careers of the smaller printers – those with much shorter careers – who operated a press in Wittenberg between 1525 and 1550. They can be divided into two groups: those who tried to set down roots in Wittenberg, but ultimately ended up establishing presses elsewhere, and those who arrived towards the end of Luther’s life but endured, continuing to operate after his death and the political changes that followed after the Schmalkaldic War in 1547. Both groups maintained active relationships with the larger printing houses, something which can be revealed more fully by tracking the sharing and reuse of woodblocks. An integrated and active network existed between Wittenberg’s printers which has heretofore not been fully acknowledged or documented.

The Minor Printers in Reformation Wittenberg

By 1525, at the height of the Reformation’s polemical pamphlet campaigns, there were ten printers active in Wittenberg. In only a few years the local printing scene had grown from a small, single-printer market into a saturated field. Competition was tough and not every workshop survived. Nevertheless many sought to carve their way into the market.

Hans Barth began printing in Wittenberg in early August 1525 right at the end of the German Peasants’ War. At first he worked with a partner, Hans Bossow, with whom he printed two books.4 However, by September Barth was printing independently. Over the next two years he printed only around two dozen books, half of which were by Luther. He also printed six works by Johannes Bugenhagen, who introduced the Reformation in Pomerania and Denmark, foreshadowing Barth’s future career. In 1527 Barth left Wittenberg for Magdeburg, but ultimately settled in Denmark. Magdeburg’s proximity to Wittenberg attracted other printers who were pushed out of Wittenberg’s market. When Michael Lotter, son of one of Leipzig’s leading printers, left Wittenberg, he too moved to Magdeburg and ultimately dominated the local industry. Recognising the increased competition, Barth packed up shop again, this time for Roskilde, outside of Copenhagen.

After moving to Magdeburg in 1527, Barth continued using a Wittenberg imprint for some of his early publications. In two of his first works that year he listed ‘Wittenberg’ in the imprint but stated in the colophon that he was printing in Magdeburg.5 He repeated the practice two more times the following year.6 But in his edition of Luther’s Das doepboekeschen vordudeschet up dat nye thogericht, he used a false Wittenberg imprint without listing Magdeburg in the colophon.7 Counterfeiting books from Wittenberg was not unique to printers in Magdeburg; printers in all the major cities of the Empire used false Wittenberg imprints in their reprints of Luther’s works. This practice was less successful in Magdeburg, as being near to Wittenberg made it more likely that the town would be flooded with original editions from Wittenberg before printers could reprint the books. Their advantage was editing texts to the Low German vernacular spoken by northern readers.8

Like Barth, Hans Weiss also began printing in Wittenberg in 1525. Originally from Kronach in Franconia, he arrived in Wittenberg in 1520, where he is listed in the university matriculation book.9 One of his first works was helping Rhau-Grunenberg complete an edition of Luther’s Auslegung der Episteln und Evangelium vom Advent an bis auff Ostern, a large folio of Luther’s biblical exegesis arranged around the liturgical calendar.10 At the urging of Philipp Melanchthon, Weiss tried to establish a press in Breslau, but was unsuccessful.11 In 1535, he became the guardian of the children of another local printer, Symphorian Reinhart. Reinhart was the Bettmeister (“Bed master”) to the Elector of Saxony, for whom he also operated a private press in the electoral castle for several years.12 Throughout his time in Wittenberg, Weiss printed nearly a hundred editions of which two-thirds were by Luther. In 1539 he established the first printing press in Berlin, where he was given a monopoly by Joachim II, the Elector of Brandenburg.13 Although he died in 1543, his heirs continued operating the press for four more years. After the press ceased production, Berlin remained without a printer for nearly three decades.

Unlike Weiss, the next printer, Hans Frischmut, had only a short career in Wittenberg. Frischmut operated a press in Wittenberg between 1538 and 1541. It appears he took over printing equipment that originally belonged to the workshop of Lucas Cranach and Christian Döring, as he reused some of their earlier material.14 Although he printed fewer than two dozen editions in Wittenberg, only five were by Luther, as Frischmut printed works by other reformers, including Melanchthon, Veit Dietrich and Justus Jonas. He eventually relocated to Halle in 1541, likely at the prompting of Jonas.15 While there he was imprisoned for printing a work by Luther that was critical of the Elector of Mainz, Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg, who had a residence in Halle.16

Although Wittenberg was a crowded marketplace for printers, those who were unable to thrive in Wittenberg were able to establish successful presses elsewhere. In this sense, Wittenberg was a launching pad to successful careers. Their experience, connections and proximity to Luther in Wittenberg was likely advantageous when setting up shops in new towns. The next three printers differ from those already mentioned in that they did not end up moving to another town. Instead they arrived after others had moved away and were able to keep operating after Luther’s death, which also coincided with the deaths of three of the four most active printers in Wittenberg. This opened up some space in the market, into which newer and smaller printers could prosper.

Peter Seitz opened a workshop in 1534. This was an important year in Wittenberg’s printing history, as it was the year Lufft printed the first edition of Luther’s German translation of the complete Bible.17 The privilege to print Luther’s Bible translation also included a privilege for his translation of the Book of Sirach.18 Seitz printed an edition of this text in 1540 featuring a title-page border with the coat of arms of the Elector of Saxony, presumably in reference to the privilege.19 Although he was active in Wittenberg for fourteen years, he only printed just over fifty editions. His workshop continued after his death in 1548, but there appears to have been a dispute amongst his heirs. After Seitz’s death, his wife, Ursula, took over the shop. In 1548, she printed two editions listing her name in the colophon.20 In 1550 her son, also named Peter, is listed in an edition of Luther as ‘Peter Seitz the Younger’.21 However, for most of the 1550s the workshop printed under the name of ‘the heirs of Peter Seitz’. They printed nearly 150 editions, far more than when the elder Seitz ran the shop. It was not until 1557 that the young Peter began printing under his own name. Perhaps his mother had died or they finally came to an agreement. Peter continued printing until his death in 1577, at which point his heirs continued the operation for a further two years.

The next printer to arrive in town was Veit Kreutzer who began printing in 1541 and continued for the next twenty-two years. Although he printed at least 360 books during this period, far more than the other printers in the chapter, very little is known about him. Nearly a third of his publications were works by Melanchthon. Unlike Luther who published regularly in German, most of Melanchthon’s works were published in Latin. Likewise, almost two-thirds of Kreutzer’s publications were in Latin.

The last printer, Johannes Krafft, did not begin printing until 1546, the year of Luther’s death. He was born around 1510 in Usingen, a town north of Frankfurt. He married Margarete Pfeiffer from Kemberg with whom he had three sons and a daughter, Zacharias, Johann, Magdalena and Philipp.22 He printed only one edition in 1546 and the next edition with his name did not appear until 1549, after the death of Georg Rhau, suggesting he may have worked in Rhau’s workshop. He printed more than 850 editions over his career, including more than 180 by Melanchthon. From the mid-1560s he regularly attended the Frankfurt Fair and later became a member of the town council. He died in 1578 and his son Johann continued the enterprise into the seventeenth century.

Some of the previously mentioned printers appear to have contributed little to the print industry in Wittenberg either due to issuing few publications, having quickly moved to another town, or having arrived too late on the scene for the scope of this chapter, yet flourishing in the second half of the century. Although they played only minor roles in the shadows of much larger printing houses, an investigation into their printing materials shows they were fully integrated into the local industry and had working relationships with the larger workshops.

Tracing Woodcuts

In the Holy Roman Empire, there were no standardised practices used by printers for the publication information in their books. Printers listed their names, places of publication and years of publication in a variety of ways, often with information split between the imprint on the title-page and the colophon at the end of the book. Sometimes printers listed the city and year in the imprint and their name in the colophon. Often, they listed nothing at all. In these cases, it can be difficult to determine the printer of a book. One way to identify a printer is by examining the typefaces used in the publications. Unfortunately, this method is difficult to apply to printers in Wittenberg, as many used the same Schwabacher typefaces.23 Another method is by examining ornamental and illustrative woodcuts, which printers reused across multiple publications. If a woodcut used in a work by an anonymous printer can be identified in a work where a printer’s name is listed – especially if it appeared in the same or surrounding years – an attribution is highly likely. But such a method requires a large corpus documenting woodcut usage. Until recently, there has been no list systematically identifying which books from early modern Europe contained illustrations or ornamentation. In collaboration with Alexander S. Wilkinson, our Ornamento project at University College Dublin used machine learning to compile a list of 5.6 million illustrations and ornamentations used across nearly 165,000 books between the period 1450 and 1600.24 Moreover, we applied image matching technology to find instances of the same woodcuts being used across multiple editions. Not only is this advantageous for identifying printers of anonymous works, but also for documenting the use and reuse of woodcuts and how they often passed between several workshops.

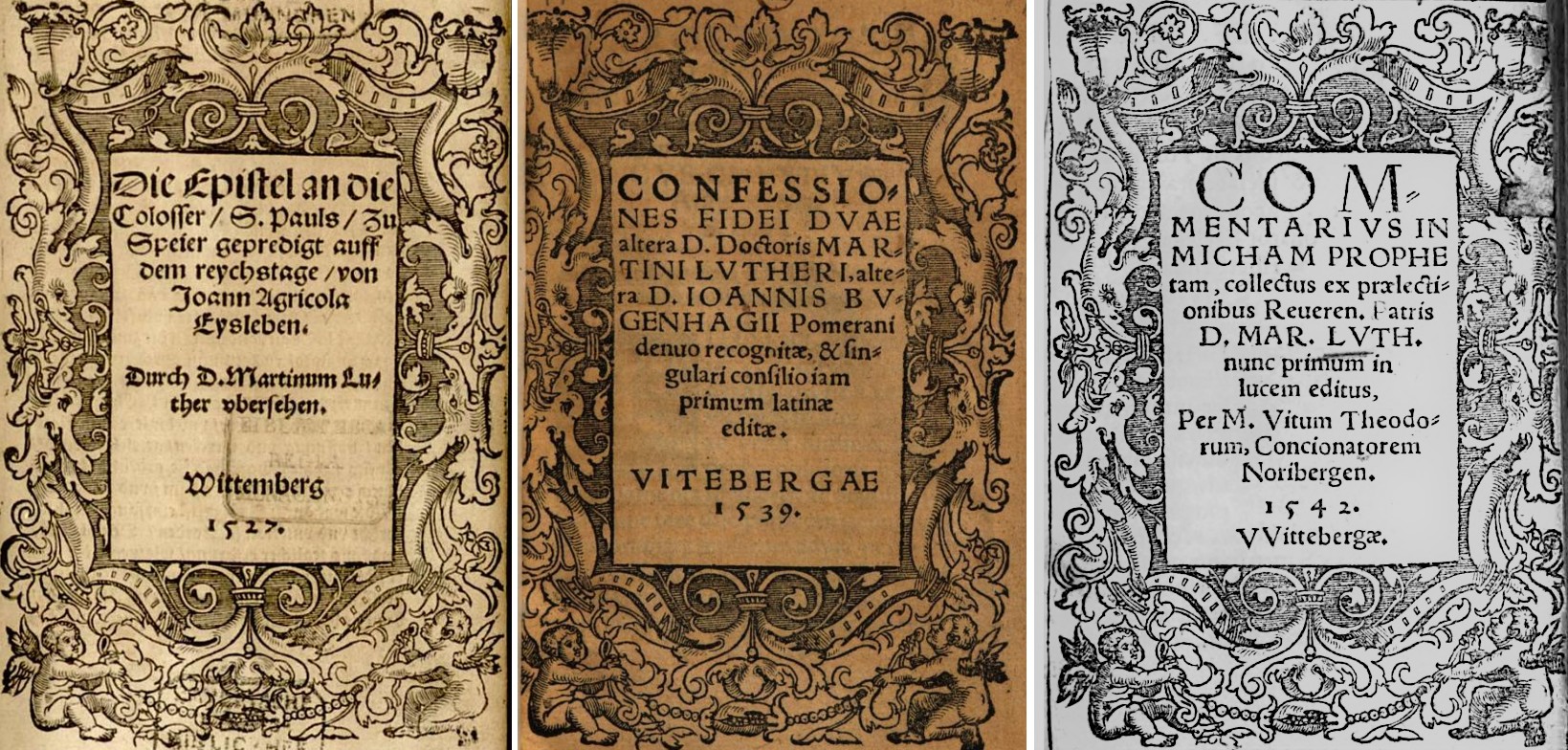

In Wittenberg, this methodology can help us better understand the history and activity of smaller workshops. Because several printers tried to establish presses, it was important to get up and running quickly. If they were new to the trade, it was often easier and cheaper to purchase used material from other workshops instead of commissioning new woodcuts. Several printers in Wittenberg opted for this route. Hans Weiß, who began printing in 1525, had material from the Lotter workshop. Between 1523 and 1525, Melchior Lotter and his brother Michael used a border featuring lions in the bottom corners, which they used in a dozen editions.25 This border was later used by Weiß in his first year of activity for one of Luther’s sermons.26 Hans Frischmut also used material from a former local workshop. In a 1541 edition of Veit Dietrich’s Summaria uber das alte Testament, Frischmut used a large calligraphic letter D half a dozen times at the beginning of new sections.27 This letter came from the workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder and Christian Döring. It was used in their edition of Luther’s German translation of the historical books of the Old Testament published in 1524.28 Frischmut continued using this initial after he relocated to Halle. Frischmut also used a border that was first used by Symphorian Reinhart, who operated a private press located in the Electoral Castle for official print.29 In 1539 Frischmut used this floriated border with putti in the bottom corners for an edition of Confessiones fidei duae altera, which was a Latin edition of the confessions of both Luther and Bugenhagen.30 Reinhart had used it twelve years earlier in an edition by Johannes Agricola.31 Although Frischmut eventually relocated to Halle, the border stayed in Wittenberg, employed in several editions by Veit Kreutzer.32

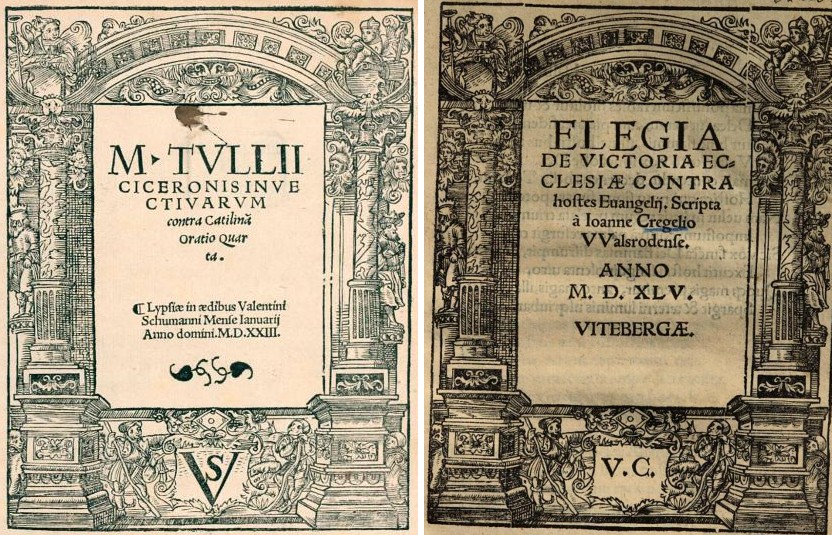

Kreutzer also used woodblocks acquired from printers outside Wittenberg. In 1545 he used an architectural border with his initials inserted into a blank shield at the bottom.33 This was a border previously used by Valentin Schumann in Leipzig in at least nine editions between 1522 and 1528. Kreutzer replaced his initials in the spot where Schumann had a monogram of his own initials.34

Kreutzer was not the only printer in Wittenberg who acquired material from other cities. Johann Krafft used illustrations originally from Strasbourg. In 1546 Krafft used an illustration of soldiers for the title-page of Ursprung und ursach gegenwertiger uffruer Teütscher nation.35 Twenty-five years earlier, the Strasbourg printer Johann Prüß used the illustration for his edition of Luther’s polemical Passional Christi und Antichristi.36 Hans Barth used woodblocks from even farther away. After leaving Wittenberg, he ended up in Roskilde near Copenhagen. In at least three books that he published there between 1534 and 1540, he used ornate initials used by Josse Badius in Paris in 1515.37 They can be confirmed as the same woodblocks rather than copies due to evidence of wear, and in particular, identical cracks around the edges.38Sometimes woodblocks changed hands permanently from one printer to the next, but in many instances borders, illustrations, devices and initials were traded back and forth. Several printers in Wittenberg used the same woodblocks in their books. Wittenberg was a small town; instances of reuse among printers is evidence of an integrated market. At the height of his prolific literary output, Luther divided up his first editions amongst the town’s printers, giving everyone a slice of the profits.39 Some reprinted the first editions produced by their peers only a short walk across town. Such reuse can complicate identifying printers, but it can also reveal the working patterns of the local printing community.

Title-page borders were often shared between workshops. In 1537 Seitz printed a work by the reformer Ambrosius Moibanus that included a title-page featuring Cranach’s Law and Grace, an allegory depicted in several of his paintings.40 This border was used a year earlier by Rhau for Melachthon’s Loci communes.41 Rhau continued using the border over the next decade, so it was not a case of Seitz purchasing the border. Klug also used the border in 1539 for a work by Urbanus Rhegius.42 In all three instances, the printers’ names are listed in the books.

Another border that passed between printers featured David and Goliath in a larger panel at the bottom. Weiß used the border in a 1534 edition of Luther’s Vom Abendmal Christi bekentnis.43 Rhau used this border in 1532 and used it nearly a dozen times over the decade, as did Schirlentz for two editions in 1542.44

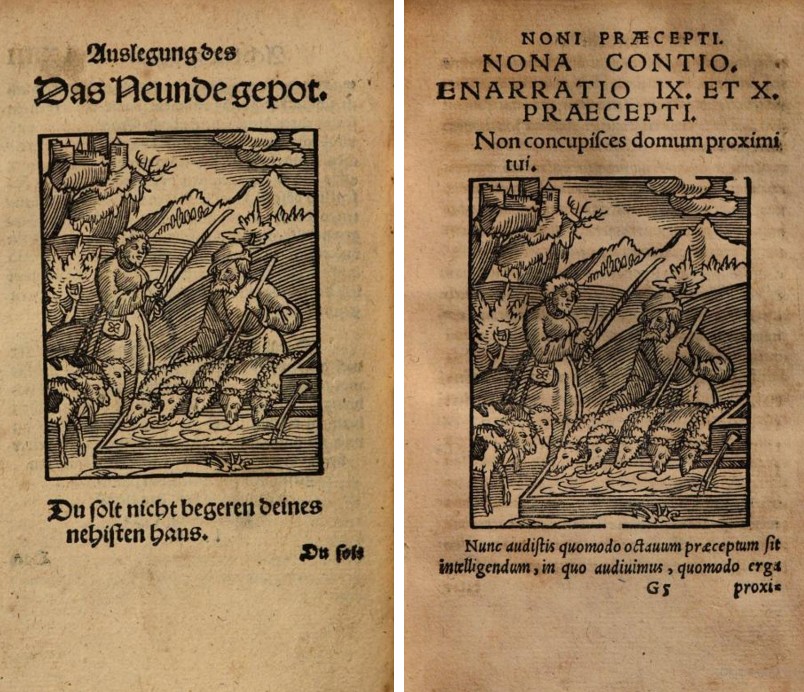

Besides borders, which were important marketing tools used on title-pages, other woodblocks used within the text were also shared. In 1539 Seitz published an octavo edition of Andreas Osiander’s catechism for children, which included two dozen illustrations.45 Seven years earlier, Rhau used the same illustrations in his edition of Luther’s German catechism.46 After Seitz, Rhau and his heirs continued to use these woodblocks through the 1560s. Seitz also reused illustrations for an edition of Luther’s Hauspostilla.47 It included dozens of illustrations, more than 150 ornate initials and a large portrait of the Elector of Saxony. The illustrations were originally used by Michael Lotter after he moved from Wittenberg to Magdeburg.48 They were then used in Wittenberg by Seitz and later by Lufft’s workshop.49

Although printers shared woodblocks, there are also examples of printers having different versions of the same composition. Both Weiß and Lufft had copies of an ornate initial depicting St Paul. Weiß used it at the beginning of each of Paul’s epistles for an edition of Luther’s Low German translation of the New Testament published in 1526.50 Lufft used his version of the initial in 1535, also in an edition of Luther’s Low German New Testament.51 Both initials appear identical and could easily be mistaken as the same woodblock, but there are minute differences in the execution.

Even printer’s devices were shared amongst printers in Wittenberg. Between 1553 and 1565, Krafft, Kreutzer, Lufft and the heirs of Georg Rhau used a device on their title-pages featuring God the Father joining Adam and Eve’s hands together in matrimony.52 In each instance, the device appears in the traditional location on the title-page above the imprint. Krafft’s, Lufft’s and Rhau’s workshops used the same woodblock, whereas Kreutzer’s was a variant. Some of the editions with this device were about marriage, so the device seems to have been used in these cases not so much as a logo or workshop branding opportunity, but as ornamentation to complement the subject matter.

The examples discussed above clearly demonstrate how the community of printers in Wittenberg regularly exchanged and reused each other’s materials. In some cases, woodblocks passed from one workshop to the next but in several cases they passed back and forth, evidence of borrowing, as opposed to acquiring. While this represents sharing among printers, there are several examples that indicate intentional collaboration between workshops, shifting our understandings of the activity of Wittenberg’s leading print houses.

There are a few cases of printers in Wittenberg collaborating with printers in other towns. In 1539 Frischmut published a work by Urbanus Rhegius on identifying false prophets.53 However, Andreas Goltback in Braunschweig published the same work the same year.54 Both printers used the same large illustration on the title-page depicting the biblical idiom of a wolf in sheep’s clothing, in this case, with two wolves dressed as catholic priests devouring a sheep. Both printers also used the same large typographical initial E at the beginning of the text. Although the type is laid out differently, they clearly were using the same design.

Frischmut only worked in Wittenberg for four years. Some of the other minor printers that remained longer were able to establish working relationships with the larger presses. In 1534, Hans Weiß printed a sermon by Luther on the prayer of Jesus in John 17. The title-page border depicts Christ as the good shepherd surrounded by the emblems of Luther, Melanchthon, Jonas, Bugenhagen and Caspar Creutziger.55 This is the only instance I could find where Weiß used this border. Between 1533 and 1539, Lufft used it at least fifteen times. In 1534, the year Weiß used the border, Lufft printed the first edition of Luther’s German translation of the complete Bible, which accounted for nearly three-quarters of his press activity that year. Because Lufft’s presses were busy with the largest project of his career, it is possible that he loaned the border to Weiß to print the sermon.

Weiß also regularly used an architectural border featuring the Luther rose at the bottom, which was an emblem adopted by printers in Wittenberg to act as a seal of authenticity that the work in question was authorised by Luther.56 Weiß used this border in at least fifteen editions between 1529 and 1533, all but once for works by Luther. In 1531, however, there were three editions with this border that listed Georg Rhau in the colophon.57 Rhau used at least fifty-eight borders throughout his career.58 Either Rhau borrowed Weiß’s border for these three works or Weiß printed them on behalf of Rhau. They all included ornate initials used by Rhau in other works, but were also used by Weiß or other printers.

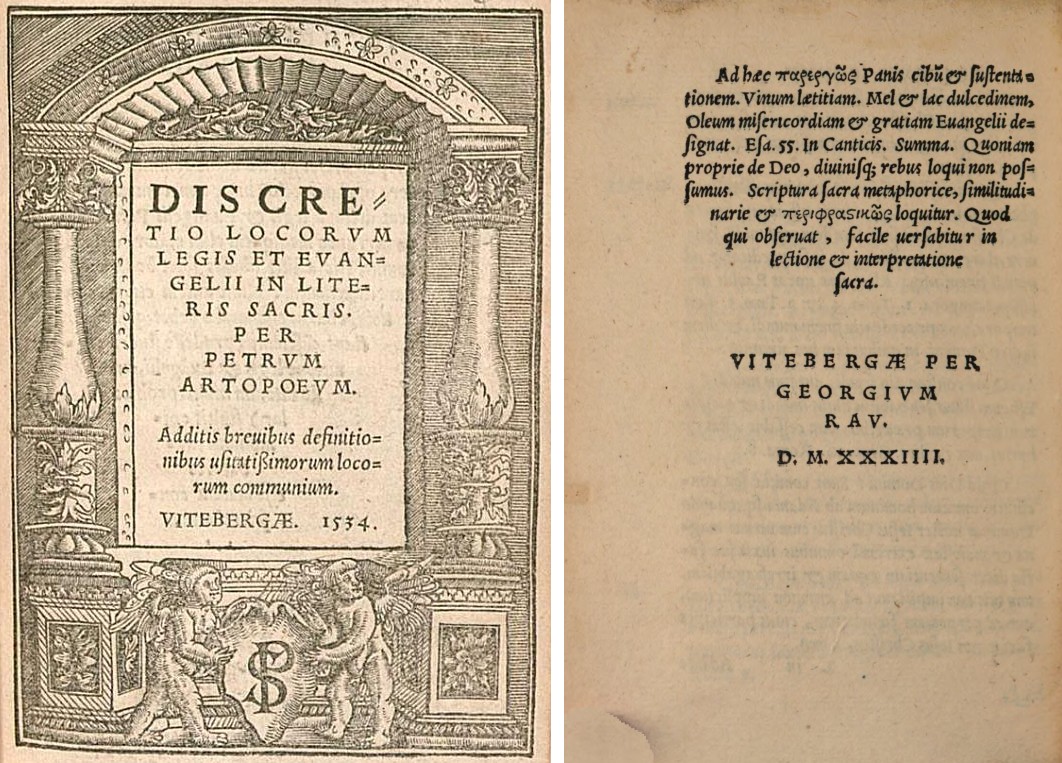

There is also evidence of Rhau collaborating with Peter Seitz. In 1534, Rhau published a work by the German theologian Peter Becker.59 Rhau’s name is clearly listed in the colophon and is the only name present; the imprint only lists Wittenberg and the year. However, the architectural title-page border features an arch at the top and two putti at the bottom holding a shield with Seitz’s initials. The border was used in another edition the same year and again in 1536; both editions were by Seitz with his name printed in the colophon.60

The same situation occurred again that year – but with a different border – in Rhau’s edition of Bellum grammaticale by Andrea Guarna.61 This border was also architectural, but with a triangular pediment at top and a putto at the bottom holding a shield with Seitz’s initials. No printer is listed in the imprint and only Rhau’s name appears in the colophon. The border was used in two other editions that year and again five years later. Seitz’s name is listed in the colophon of all three editions.62 While it is possible that Rhau borrowed Seitz’s border, it seems unlikely that Rhau would have used a border with another printer’s monogram, especially since he had the most borders among the town’s printers and had no need to borrow. Rather, Rhau’s presses were probably too busy for him to undertake the work and he subcontracted the project to Seitz. This would explain Rhau’s name in the colophon and the absence of Seitz’s, though one does wonder how Rhau would have reacted on seeing Seitz’s monogram on the title page of a work credited to his workshop. Why would a printer like Seitz agree to publish material under a different printer’s name? Wittenberg was a crowded market and he may have been happy to receive the commission. It is also likely that Seitz received payment for his work, but it was Rhau who assumed the financial risk of the project.

Conclusions

Early modern printers owned several typefaces and woodblocks, some that they alone used and others that passed between or from one workshop to the next. That printers shared and reused woodblocks demonstrates the culture of exchange of printing materials that took place in Wittenberg during the Reformation. By documenting this exchange we can better understand patterns of usage and the working relationships of a local industry. Within this network, there is clear evidence that larger printing houses subcontracted projects to their smaller peers. Wittenberg was a crowded market with many printers moving elsewhere because they were unable to establish a profitable business. Subcontracted projects could offer attractive work to smaller enterprises, similar to jobbing printing, as they would be paid for the entire project without having to undertake the financial risk or worry about problems of marketing and distribution.

While this hypothesis of collaboration and subcontracting is based upon patterns of exchange and reuse of woodblocks, it would be strengthened by evidence of contractual relationships in archival sources and by including typographical analysis. Although printers in Wittenberg often used the same typefaces, an investigation into damaged and broken type could provide further evidence of which printing houses produced the editions.63 Paper watermark analysis would be less effective as printers might have used the same suppliers or bought, sold and exchanged paper with each other.

Finally, this research calls for us to re-examine how we assess printers’ production volumes. Smaller workshops may in fact be considered smaller because the works they produced on behalf of others are not reflected in their output. Likewise, many of the works credited to the large, established printing houses may have actually been produced by other workshops. This is particularly true for works where the printer is inferred. Of the records in the Universal Short Title Catalogue and the German national catalogue of the sixteenth century (VD16) that have inferred printers, nearly all have no information detailing why a particular printer is associated with a specific edition. Given that even books with a printer listed could have been printed in collaboration with another workshop, it complicates attribution efforts and how we interpret production volumes. Printing during the Reformation brought many new printers into the industry, but the ruthless competition made success difficult. Despite this competition, the analysis of printers’ ornamental and illustrative materials demonstrates that printers regularly shared equipment with each other and built collaborative relationships to meet the demands of a growing industry.

For more on Rhau-Grunenberg’s pre-Reformation career, see Maria Grossmann, ‘Wittenberg Printing, Early Sixteenth Century’, Sixteenth Century Essays and Studies, 1 (1970), pp. 53-74. For an introduction to the Lotter workshop, see Walter G. Tillmanns, ‘The Lotthers: Forgotten Printers of the Reformation’, Concordia Theological Monthly, 22 (1951), pp. 260-64; Richard G. Cole, ‘Reformation Printers: Unsung Heroes’, The Sixteenth Century Journal, 15 (1984), pp. 333-34.↩︎

Martin Luther (trans.), Das Newe Testament (Wittenberg: Melchior II Lotter for Lucas Cranach and Christian Döring, 1522), USTC 627911.↩︎

For an in-depth look at the workshops of Klug, Lufft, Rhau and Schirlentz, see Drew B. Thomas, The Industry of Evangelism: Printing for the Reformation in Martin Luther’s Wittenberg (Leiden: Brill, 2021).↩︎

USTC 661048 and 656841.↩︎

USTC 679050 and 679488.↩︎

USTC 627045 and 627853.↩︎

Luther, Das doepboekeschen vordudeschet up dat nye thogericht (Wittenberg [=Magdeburg]: Hans Barth, 1528), USTC 627045. Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibliothek, M: Li 5497.1 (1).↩︎

For more on the practice of counterfeiting Wittenberg books as well as counterfeiting in Magdeburg, see Thomas, The Industry of Evangelism, ch. 3 and ‘The Lotter Printing Dynasty: Michael Lotter and Reformation Printing in Magdeburg’, in Elizabeth Dillenburg, Howard Louthan and Drew B. Thomas (eds.), Print Culture at the Crossroads: The Book and Central Europe (Leiden: Brill, 2021), pp. 253-259.↩︎

Christoph Reske, Die Buchdrucker des 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts im deutschen Sprachgebiet: auf der Grundlage des gleichnamigen Werkes von Josef Benzing (2nd ed., Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2015), p. 1085.↩︎

Luther, Auslegung der Episteln und Evangelien vom Advent an bis auff Ostern (Wittenberg: Johann Rhau-Grunenberg and Hans Weiss, 1525), USTC 614280.↩︎

Reske, Die Buchdrucker des 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts im deutschen Sprachgebiet, p. 1085.↩︎

Thomas Lang, ‘Simprecht Reinhart: Formschneider, Maler, Drucker, Bettmeister – Spuren eines Lebens im Schatten von Lucas Cranach d. Ä.’, in Heiner Lück (ed.), Das ernestinische Wittenberg: Spuren Cranachs in Schloss und Stadt, (Petersberg: Michael Imhof Verlag, 2015), pp. 93-138.↩︎

Cole, ‘Reformation Printers’, p. 335.↩︎

Reske, Die Buchdrucker des 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts im deutschen Sprachgebiet, p. 1086.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

The work was Luther’s New Zeitung vom Rein (Halle: Hans Frischmut, 1542), USTC 677162.↩︎

Luther (trans.) Biblia das ist die gantze heilige schrifft Deudsch (Wittenberg: Hans Lufft, 1534), USTC 616653.↩︎

Bible privileges were lucrative in Wittenberg. For more on the history and development of such privileges in Wittenberg, see Hans Volz, ‘Wittenberger Bibeldruckprivilegien des 16. und Beginnenden 17. Jahrhunderts’, Gutenberg-Jahrbuch (1955), pp. 133-39.↩︎

Luther (trans.), Jhesus Syrach zu Wittemberg verdeudscht (Wittenberg: Peter Seitz, 1540), USTC 668848.↩︎

Moritz Breunle, Ein kurtz formular und Cantzley buechlein, darinn begriffen wird wie man einem jeglichen schreiben sol (Wittenberg: Ursula Seitz, 1548), USTC 644269 and 644270. Although I was only able to view one of the books, they may be different states of the same edition, one with Roman foliation, the other with Arabic. It is yet to be determined if the text was reset.↩︎

Luther, Die heubtartikel des Christlichen glaubens wider den Bapst und der hellen pforten zu erhalten (Wittenberg: Peter II Seitz, 1550), USTC 636807.↩︎

Reske, Die Buchdrucker des 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts im deutschen Sprachgebiet, p. 1087.↩︎

This method also requires physical inspection of surviving copies to measure the typefaces, a practice that is currently unfeasible at scale to scanned surrogates available online.↩︎

For more about Ornamento see Alexander S. Wilkinson’s contribution to this volume.↩︎

As an example, see the border used in Lotter’s 1523 edition of Luther’s On the Freedom of a Christian. Luther, Von der freyheit eynes Christenmenschen (Wittenberg: Melchior Lotter, 1523), USTC 703476. Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, 4 Polem. 1863.↩︎

Luther, Eyn sermon von stercke und zunemen des glawbens und der liebe. Aus der Epistel s. Pauli zun Ephesern (Wittenberg: Hans Weiß, 1525), USTC 656642. Halle/Saale, Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Sachsen-Anhalt, Id 6266 (5).↩︎

Veit Dietrich, Summaria uber das alte Testament darinn auffs kuertzste angezeigt wird was am noetigsten und nuetzsten ist dem jungen Volck und gemeinem man aus allen capiteln zu wissen und zu lernen (Wittenberg: Hans Frischmut, 1541), USTC 694912. Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, 4 Asc. 252. The first instance of the initial is on f. L1r.↩︎

Luther (trans.), Das ander teyl des Alten Testaments (Wittenberg: Lucas Cranach and Christian Döring, 1524), USTC 626822. Augsburg, Staats- und Stadtbibliothek, 2 Th B VII 10, f. CXCIX.↩︎

See footnote 12.↩︎

Luther and Johannes Bugenhagen, Confessiones fidei duae altera D. Doctoris Martini Lutheri, altera D. Joannis bvgenhagii Pomerani denuo recognitae, et singulari consilio iam primum Latinae editae (Wittenberg: Hans Frischmut, 1539), USTC 624617. Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Alt Prunk 79.X.43.↩︎

Johannes Agricola, Die Epistel an die colosser S. Pauls zu Speier gepredigt auff dem Reychstage (Wittenberg: Symphorian Reinhart, 1527), USTC 636598. Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Rar. 1655.↩︎

See Luther’s Commentarius in micham prophetam, collectus ex praelectionibus reveren (Wittenberg: Veit Kreutzer, 1542), USTC 623233. Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Exeg. 726. Kreutzer added an outline around the border, but it is clear it is the same woodblock used by Reinhart and Frischmut due to spots of wear in the same locations.↩︎

Johannes Kregel, Elegia de victoria ecclesiae contra hostes evangelii. Scripta à Joanne cregelio vvalsrodense (Wittenberg: Veit Kreutzer, 1545), USTC 649087. Augsburg, Staats- und Stadtbibliothek, 4 NL 105.↩︎

See Cicero’s Invectivarum contra catilinam oratio quarta (Leipzig: Valentin Schumann, 1523), USTC 674579. Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, 4 A.lat.b. 750,8.↩︎

Martin Schrot, Ursprung und ursach gegenwertiger uffruer Teütscher nation (Wittenberg: Johann I Krafft, 1546), USTC 704511. Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Res/4 P.o.germ. 238,8.↩︎

Luther, Passional Christi und Antichristi (Strasbourg: Johann Prüß, 1521), USTC 683165. Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, 15032-B ALT RARA, f. C1r.↩︎

For more on the connections between the Parisian and Danish book markets, see Wolfgang Undorf, From Gutenberg to Luther: Transnational Print Cultures in Scandinavia 1450-1525 (Leiden: Brill, 2014), p. 20, see also chapters 1 and 2.↩︎

Compare the initial D used in: Jan van Campen, Interpretatio paraphrastica psalmorum (Roskilde: Hans Barth, 1536), USTC 302078. Copenhagen, Det Kongelige Bibliotek, Hielmst. 17 8°, f. Z1v; Alle Epistler oc Evangelia som lesiss alle Søndage om Aared, sammeledis Juledag, Paaskedagh, Pingetzdag, meth deriss Udtydning oc Glose oc eth Jertegen till huer Dag (Paris: Josse Badius, 1515), USTC 302635. Copenhagen, Det Kongelige Bibliotek, LN 208 2°, f. G2v.↩︎

Hans Volz, ‘Die Arbeitsteilung der Wittenberger Buchdrucker zu Luthers Lebzeiten’, Gutenberg-Jahrbuch, 32 (1957), pp. 146-54.↩︎

Ambrosius Moibanus, Das herrliche mandat Jhesu Christi unsers Herrn und heilandes (Wittenberg: Peter I Seitz, 1537), USTC 627461. Halle, Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Sachsen-Anhalt, Ib 3708 (2). For more on Cranach’s use of this allegory, see Günter Schuchardt, Gesetz und Gnade: Cranach, Luther und die Bilder (Eisenach: Museum der Wartburg, 1994).↩︎

Philipp Melanchthon, Loci communes das ist die furnemesten artikel Christlicher lere Philippi Melanch. Aus dem Latin verdeudscht durch justum jonam (Wittenberg: Georg Rhau, 1536), USTC 673407. Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Alt Prunk 20.Dd.36.↩︎

Urbanus Rhegius, Dialogus von der schoenen predigt die Christus Luc. 24. Von Jerusalem bis gen Emaus den zweien juengern am Ostertag aus Mose und allen Propheten (Wittenberg: Josef Klug, 1539), USTC 636000. Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, 4 Exeg. 707.↩︎

Martin Luther, Vom Abendmal Christi bekentnis (Wittenberg: Hans Weiß, 1534), USTC 702184. Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Alt Prunk 77.G.35.↩︎

Rhau used this border for a copy of Melanchthon’s Vom Abendmal des Herrn etliche sprueche der alten veter trewlich angezogen (Wittenberg: Georg Rhau, 1532), USTC 702185. Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, 4 Polem. 2049. For an example by Schirlentz, see Luther’s Eine heerpredigt wider den Tuercken (Wittenberg: Nickel Schirlentz, 1542), USTC 646131. Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, 4 Hom. 1112.↩︎

Andreas I Osiander, Techismus pro pueris et juventute, in ecclesiis et ditione illustriss. (Wittenberg: Peter I Seitz, 1539), USTC 620275. Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Alt Prunk 80.L.70.↩︎

Martin Luther, Deudsch catechismus (Wittenberg: Georg Rhau, 1532), USTC 635668. Augsburg, Staats- und Stadtbibliothek, Th Pr 1596.↩︎

Martin Luther, Hauspostilla uber die Sontags und der fuernemesten feste Evangelien, Durch das gantze jar. Mit vleis auffs new ubersehen, gebessert, und mit XIII. predigten, von der passio gemehret (Wittenberg: Peter I Seitz, 1546), USTC 661708. Regensburg, Staatliche Bibliothek, 999/2Theol.syst.151.↩︎

Martin Luther, Auslegunge der Evangelien von Ostern bis auffs Advent gepredigt zu Wittemberg. Auffs new ubersehen und gebessert mit etzlichen sermonen mit schönen figurn und vleissigem register (Magdeburg: Michael Lotter, 1529), USTC 613947. Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Alt Prunk 77.O.29.↩︎

Martin Luther, Außlegung der Episteln und Evangelien: von Ostern bis auff das Advent. Auffs new zugericht (Wittenberg: Hans Lufft, 1547), USTC 614434. Halle, Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Sachsen-Anhalt, Ib 3725 b, 4° (2).↩︎

Martin Luther (trans.), Dat Nye Testament (Wittenberg: Hans Weiß, 1526), USTC 675270. Stuttgart, Württembergische Landesbibliothek, B niederdt.152602. See f. f4r.↩︎

Martin Luther (trans.), Dat Nye Testament (Wittenberg: Hans Lufft, 1536), USTC 628280. Stuttgart, Württembergische Landesbibliothek, B niederdt.153601, f. n3v.↩︎

See the title-pages of USTC 619241 (Krafft), 635119 (Kreutzer), 652243 (Lufft) and 635116 (heirs of Rhau).↩︎

Urbanus Rhegius, Wie man die falschen Propheten erkennen ja greiffen mag ein predig zu Mynden inn Westphalen gethan (Wittenberg: Hans Frischmut, 1539), USTC 706974. Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, 4 Hom. 1823.↩︎

USTC 706973. Regensburg, Staatliche Bibliothek, 999/4Theol.syst.645(7.↩︎

Martin Luther, Das siebenzehend capitel Johannis von dem gebete Christi (Wittenberg: Hans Weiß, 1534), USTC 628017. Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, 4 Hom. 1086.↩︎

See Hans Volz, ‘Das Lutherwappen als “Schuzmarke” ’, Libri, 4 (1954), pp. 216-25. See also, Thomas, The Industry of Evangelism pp. [insert page numbers; waiting on proof].↩︎

There are actually four editions listed in the USTC and VD16 that list Rhau as the printer, but one is only an inferred attribution.↩︎

Thomas, Industry of Evangelism, p. [insert page number; awaiting proof]↩︎

Peter Becker, Discretio locorum legis et evangelii in literis sacris. Per Petrum artopoeum.additis brevibus definitionibus usitatißimorum locorum communium (Wittenberg: Georg Rhau, 1534), USTC 637769. Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Asc. 1704#Beibd.2.↩︎

USTC 637768 and 673159.↩︎

Andrea Guarna, Bellum grammaticale (Wittenberg: Georg Rhau, 1534), USTC 615729. Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Res/L.lat. 44#Beibd.2.↩︎

USTC 615727, 671607 and 693512.↩︎

This method has been used successfully by Christopher N. Warren, Pierce Wiliams, Shruti Rijhwani and Max GSell, ‘Damaged Type and Areopagiticas Clandestine Printers’, Milton Studies, 62 (2020), pp. 1-47.↩︎