Circumventing Censorship:

The Rise and Fall of Reformation Print Centres

This work examines the impact of censorship on the printing industry during the Reformation era. Focusing on the cities of Leipzig and Wittenberg, the article traces the rise of Leipzig as a major print centre and its subsequent decline due to the ban on printing Martin Luther’s works. Leipzig’s printers resorted to various strategies to circumvent the ban, including printing counterfeit editions and establishing branch offices in other territories. The article also discusses the rise of the Wittenberg industry and the importance of considering sheet totals rather than edition totals to accurately assess production volumes. Through a comprehensive analysis of historical records, the study sheds light on the challenges faced by printers and their attempts to profit from the Reformation movement while navigating censorship.

Notice: This document is a post-peer review author accepted manuscript of Drew B. Thomas, “Circumventing Censorship: The Rise and Fall of Reformation Print Centres” in Alexander Wilkinson and Graeme Kemp (eds.), Negotiating Conflict and Controversy in the Early Modern Book World (Leiden: Brill, 2019), pp. 13-37. It has been typeset by the author and is for informational purposes only. It is not intended for citation in scholarly work and may differ in content and form from the final published version. Please refer to and cite the final published version, accessible via its DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004402522_003.

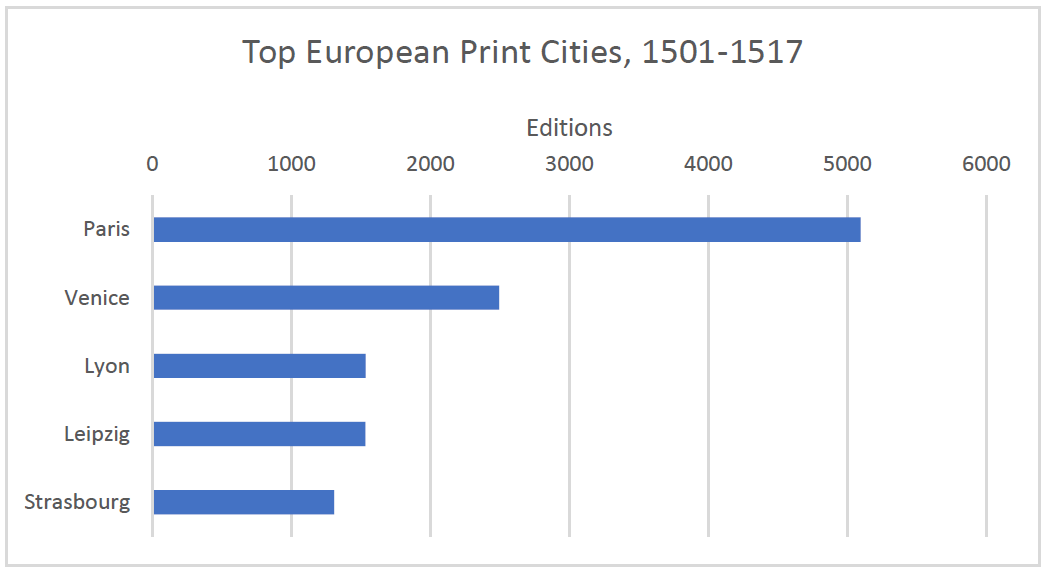

When Martin Luther published his Ninety-Five Theses in Wittenberg in 1517, Leipzig was the largest print centre in the Holy Roman Empire. Between 1501 and 1517, Leipzig’s printers produced over 1,500 editions. It was the fourth largest print city in Europe behind Paris, Venice, and Lyon.1 However, seven years later, the industry was in ruins and would only begin to recover after Luther’s death in 1546. Unfortunately, this was too little, too late. By the century’s end, Wittenberg, Leipzig’s neighbour and the home of Luther’s movement, was the Empire’s largest print city. This chapter seeks to document the rise and fall of Wittenberg and Leipzig during the Reformation and the efforts taken by Leipzig’s printers to mitigate the damage.

In documenting the rise and fall of each industry, it is possible to calculate volumes of production using an analysis by sheet totals. This is more complex than using an analysis based on surviving editions and provides a more nuanced view of press activity. In addition, we can demonstrate various ways Leipzig’s printers sought to circumvent the ban on printing Luther’s works – from printing counterfeit editions, to establishing branch offices in other territories. The result is an in depth understanding of how printers sought to profit from the rising evangelical movement even at the risk of financial ruin or imprisonment.

The Division of Saxony

In return for his loyalty to the Emperor during the Hussite uprising in Bohemia, Prince Frederick of the House of Wettin was made the Elector of Saxony, uniting Saxony with the lands of Meissen and Thuringia.2 After his death in 1428, his two sons, Frederick and William, divided Saxony in two, as was German tradition. Frederick, being the elder brother, inherited the Electoral title. However, William remained childless throughout his life, so Saxony was reunited. The new heirs, Frederick’s sons Ernest and Albert, ran into the same problem. After their father died, they also divided Saxony. According to the Treaty of Leipzig in 1485, Ernest chose how to divide Saxony and Albert chose which half he wanted. Albert chose the eastern half, which included the Saxon capital of Dresden and its largest city, Leipzig. Ernest possessed the Electoral title, as well as the ducal residences in Torgau, Jena, Weimar, Gotha, and Wittenberg. They continued to share the silver mines in Annaberg and Schneeberg.3

Losing Leipzig was a major blow for Electoral Saxony. Not only was it the territory’s largest city and its centre of commerce, it was also home to its only university and printing presses.4 Although there was a university and a local print industry in Erfurt, considered the capital of Thuringia, it was under the jurisdiction of the Archbishop of Mainz.5 The university in Leipzig was founded by scholars from the University of Prague who held competing beliefs during the Hussite wars.6 After fleeing Prague, they found refuge and support in Leipzig. Following his father’s death in 1486, the new Elector, Frederick the Wise, sought to transform Ernestine Saxony into a territory befitting of his status. When Frederick inherited the Electoral title, it was the first time the Electorate was not tied to Meissen, the more valuable territory, but to Thuringia, historically of lesser importance.7 Thus, Frederick felt the need to enhance his territory to a level expected of an imperial elector. He established many new projects in support of education and the arts. In 1502, he founded the University of Wittenberg, the first German university to be established without papal approval – though this was granted five years later.8 Frederick the Wise also embarked on new building projects to beautify his town, including the Electoral castle. He attracted leading artists, such as Jacopo de’ Barbari, Albrecht Dürer, and Lucas Cranach the Elder, who later became court painter.9 Frederick was also influential in the establishment of Wittenberg’s first commercial printing press in 1504.10 He provided funding for a common press to be used by the university, though it was to issue only a limited number of titles. Many of the faculty’s larger works were sent to Leipzig for publication.

The Division of Saxony proved instrumental in the rise of Wittenberg’s print industry. Printing Luther’s works was forbidden after the promulgation of Exsurge Domine, the papal encyclical condemning Luther and threatening him with excommunication. In many areas, including Wittenberg, the prohibition was not enforced. Leipzig was not one of those areas. Duke George was a staunch Catholic who remained loyal to Rome. He forbade printing, buying, or selling Luther’s works, even confiscating editions of Luther’s German translation of the New Testament.11 All of this led to the collapse of Leipzig’s industry.

Reformation Printing

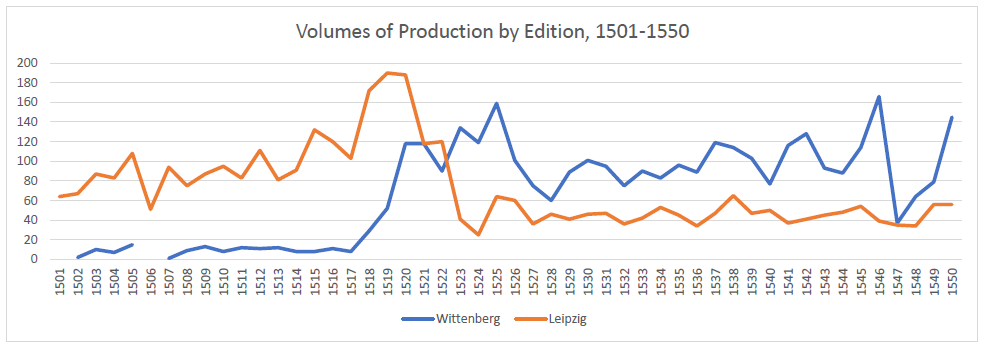

Leipzig’s first printing press arrived around 1480 due to demand from the local university. By 1500 four major printers were active in Leipzig: Konrad Kachelofen, Martin Landsberg, Melchior I Lotter, and Wolfgang Stöckel.12 Over the next decades, Leipzig would grow, eventually rising to the forefront of the German industry. Wittenberg was the exact opposite. It still lacked a printing press at the turn of the sixteenth century. Although one finally arrived in 1502, the industry remained primitive. Many scholars at the university continued to publish their works in Leipzig due to its superior printing quality and expertise. Printers came and went in the early years, when Wittenberg could barely support a press; especially since Leipzig absorbed any demand for higher quality books.13 Between 1501 and 1517, Leipzig printed over 1,500 editions, compared to Wittenberg’s meagre 135. While Leipzig regularly printed 80 to 100 editions per year, Wittenberg never surpassed 15.

Luther posted his Ninety-Five Theses near the end of 1517, a year in which Wittenberg only published eight editions. Wittenberg would never see such a year again. Luther’s movement spurred a demand for his writings that transformed the local industry. After the beginning of the Reformation, the worst year Wittenberg had over the next half century was 30 years later in 1547, when it fell to imperial troops during the Schmalkaldic War. Wittenberg’s printers published only 35 editions that year, though still more than four times as many as they had in 1517.

In only three years, Wittenberg had reached the pre-Reformation production levels of Germany’s largest centre of print – Leipzig. The small, agrarian town with only 2,000 inhabitants, became one of the largest print centres in the Empire. Every other top print city was a major centre of trade, commerce, or transportation. Wittenberg was the only city with fewer than 30,000 inhabitants.14 Its market share compared to its size was enormous. That this was the case, can be attributed largely to the work of a single printer: Johann Rhau-Grunenberg.

Rhau-Grunenberg was the first printer in Wittenberg to stay longer than a year. He arrived in 1508, the same year Luther first visited the town. Later, Rhau-Grunenberg’s press would be located in Luther’s residence at the Augustinian cloister.15 He focused mostly on works for the university and was the likely printer of Luther’s now lost first edition of the Ninety-Five Theses. During the first years of the Reformation, Rhau-Grunenberg was the only commercial printer in Wittenberg.16 Luther was scarcely complementary about Rhau-Grunenberg’s expertise. Indeed, in two letters to Georg Spalatin, one of Elector Frederick the Wise’s trusted advisors, Luther complained about the poor quality of Rhau-Grunenberg’s printing and the roughness of his typefaces, singling out in particular the editions of his own Resolutiones and Von der Beicht.17 However, despite such evidence, one cannot underestimate Rhau-Grunenberg’s greatest accomplishment: the transformation of his workshop into one of the most active in the Empire. Immediately after Luther posted his Theses, Rhau-Grunenberg picked up the pace of his production. As early as 1518 and 1519, he matched the production output of Leipzig’s printers. By 1521, he surpassed the oldest and most established printing houses in Leipzig. Collectively however, Leipzig’s five printers continued to outproduce Rhau-Grunenberg.

The Reformation also brought great success to Leipzig’s industry, at least temporarily. In 1517, Leipzig’s printers published 103 editions. Two years later in 1519, production had nearly doubled to 190 editions. Having never published a work by Luther before 1517, in only two years he represented a third of the publications printed in Leipzig. Before the Reformation, there was scarcely enough demand to support a fully developed print industry in Wittenberg. However, in the early years of Luther’s movement, there was plenty of demand for both Wittenberg and Leipzig to compete alongside each other, despite their proximity. Wittenberg’s rise did not hurt Leipzig’s industry, as it too saw a rise to new heights.

Unfortunately for Leipzig, its newfound success was short-lived. Luther’s ideas were controversial. The movement’s early debates reached their apogee in Leipzig during the summer of 1519. Duke George, who was attracted to Luther’s ideas, permitted a debate between Luther, Luther’s colleague Andreas Bodenstein von Karlstadt, and Johannes Eck, a gifted orator who was opposed to Luther’s ideas. During this disputation, Eck famously pushed Luther to support the same ideas that had led the Bohemian reformer Jan Hus to a fiery death a century earlier. He also questioned the authority of the papacy. For many in the audience, including Duke George, this was a step too far. From then onward, George was a staunch opponent of Luther and sought to rid his beliefs from his territory. After Luther was declared a heretic and outlaw at the Diet of Worms in 1521, Duke George forbade the production, buying, or selling of evangelical books within his territory.

This was to have truly disastrous effects on the Leipzig printing industry. A third of their publications were penned by Luther, but now they were forbidden from printing him. By 1524, Leipzig’s industry had plummeted. Having reached a high of 190 editions in 1519, Leipzig’s printers only published 25 editions in 1524, a level not seen since the early 1480s. Facing destitution, the printers asked the city council to petition the Duke on their behalf, as all they had to sell were Catholic works, which no one would purchase. It was Luther, they said, that readers wanted to buy.18 Duke George had little sympathy and left the ban in place. For the next few decades, Leipzig’s industry remained below their pre-Reformation levels, including after 1539 when the city officially adopted the Reformation after Duke George’s death. Failure to support or accommodate the evangelical movement resulted in the failure of the printing industry.

Volumes of Production

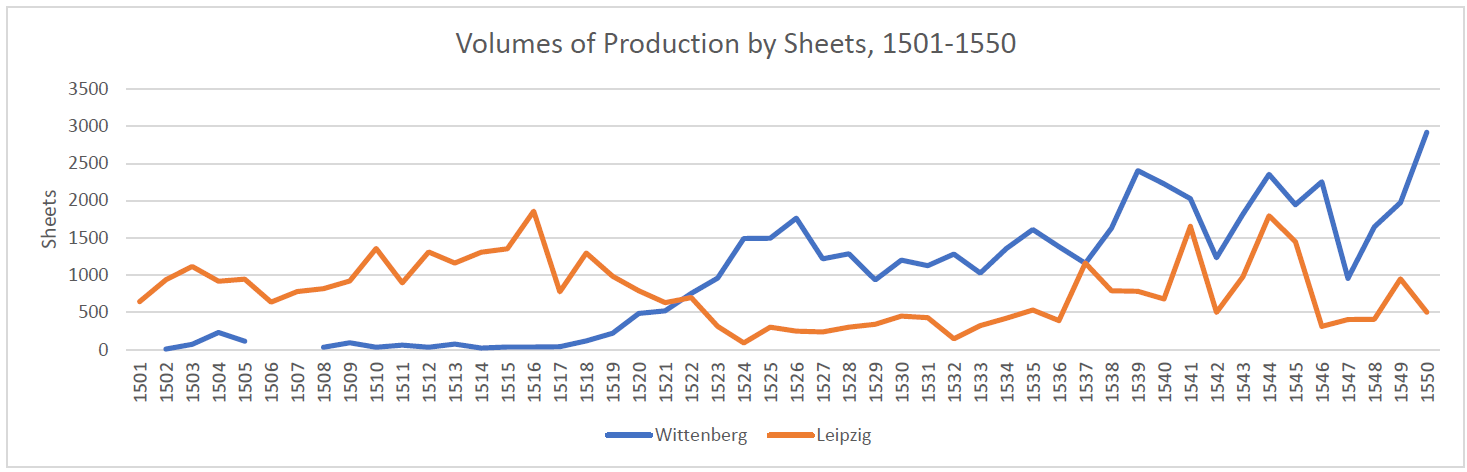

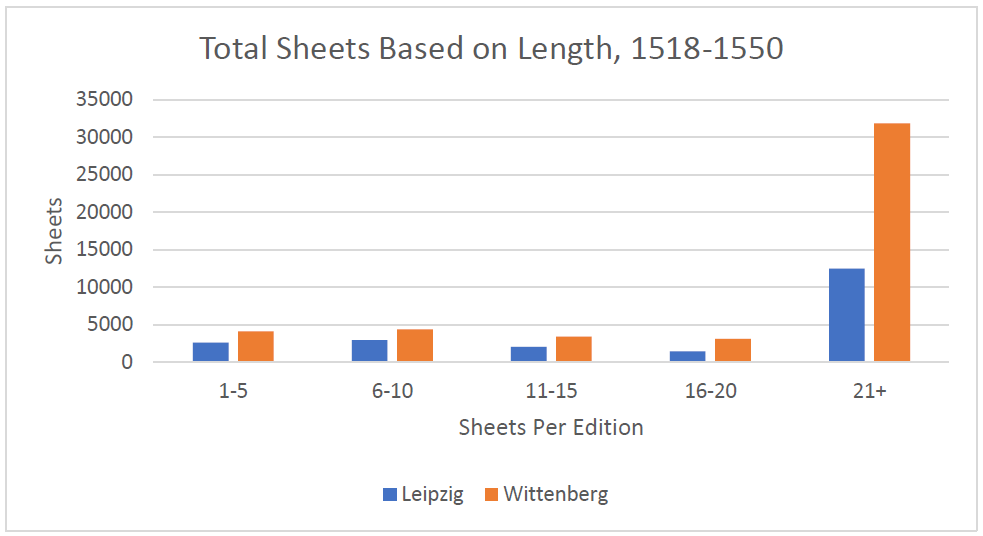

We can also re-examine Leipzig’s and Wittenberg’s publishing output based on total sheets, rather than total editions. When looking at edition totals, as above, a short work, such as a pamphlet, is considered equivalent to a longer work, such as a Bible. However, a Bible requires far more press time and many more sheets of paper to produce than a pamphlet. Treating these the same is neither fair nor accurate. Thus, an analysis by sheet totals gives each work its proper weight. This is important when looking at Wittenberg and Leipzig because, at the beginning of the Reformation, Wittenberg produced many short pamphlets. Their output could be overrepresented when compared to Leipzig, if one is only looking at edition totals.

Without the presence of large, electronically-available bibliographic projects, calculating sheet totals is near impossible. Traditionally, most historians have counted editions. In his 1981 study of Reformation pamphlets, Richard Cole conducted his research on editions within the Gustav Freytag Collection at the Stadts- und Universitätsbibliothek in Frankfurt-am-Main.19 He focused on pamphlet production over time in terms of the number of editions printed. Mark Edwards, in his seminal study Printing, Propaganda, and Martin Luther, focused on books published in Strasbourg.20 He drew conclusions of popularity based on how quickly editions were reprinted. While this information is valuable, and reveals important facets of Reformation and printing history, focusing exclusively on editions limits our understanding of contemporary production volumes. Thanks to advancements in technology and material bibliography, large, national bibliographic projects, such as VD16 and the USTC, help overcome such limitations. But even though the sample sizes have grown larger, historians have continued to limit themselves to the number of editions printed. The difficulty is gathering the necessary information to perform such calculations.

The first step is creating a database of all known editions printed in Wittenberg and Leipzig between 1501 and 1550. We can do this by drawing on data compiled in the USTC, which creates a dataset of some 3,352 Wittenberg editions printed between 1501 and 1550 and 3,590 editions for Leipzig. The second step in an analysis by sheet totals is ensuring that each edition contains two pieces of information vital for sheet calculations: foliation and format. To calculate the number of sheets required for an edition, you divide the number of folios (not pages) by the format. For example, Rhau-Grunenberg printed a quarto edition of Luther’s Der sechs und dreyssigist psalm David in 1521.21 It was 32 pages long. This means the book had 16 leaves. Dividing this by the format number, in this case four, results in four sheets of paper for each copy. Similarly, Melchior I Lotter in Leipzig printed a folio edition of Monumenta ordinis minorum in 1510.22 It was a long work, composed of 514 leaves. Dividing that by the folio number, in this case two, results in 257 sheets of paper per copy. They both appear in a catalogue as a single edition but are vastly different in terms of their size. Such calculations must be performed on all 6,942 editions for Wittenberg and Leipzig.

Unfortunately, not all the editions gathered from bibliographies and catalogues contained both pieces of required information. This deficiency was mitigated in part through physical inspection of books during multiple research trips and with individual library catalogues, which can often offer more detailed bibliographical information than union catalogues. This sheet total analysis was undertaken only for the first half of the sixteenth century. Limiting the scope to the sixteenth century ensures a period when both cities were active. I stopped at 1550, as in addition to being the mid-century mark, it allows a glimpse of the industrial response to Luther’s death in 1546 and the fall of Wittenberg to Imperial troops in 1547, which ended the Schmalkaldic War. Of the 3,352 Wittenberg editions printed in Wittenberg during these years, 3,250 records had foliation information and 3,319 had format information. In total, 3,239 records had both foliation and format information — the two vital pieces needed to calculate sheet totals. This accounts for 96.6 per cent of Wittenberg books during this period. In Leipzig, 3,208 records had foliation information, whereas 3,435 records had format information. In total, 3,143 records possessed both pieces of information, corresponding to 87.55 per cent of all Leipzig editions. Together, 91.49 per cent of all the books in the sample size had the required information to calculate sheet totals. It is only after such calculations have been performed for each edition that further quantitative analysis can be made.

The first impression when looking at Leipzig’s and Wittenberg’s production levels in terms of sheets is that the main conclusion stands. After the Diet of Worms, Leipzig’s industry collapsed, while Wittenberg’s saw great growth. The other observations, however, are no longer valid. Wittenberg’s ascendance was not as quick as previously thought. When looking at edition totals, by 1520 Wittenberg had risen to the pre-Reformation levels of Leipzig. In terms of sheet totals, however, this was certainly not the case. Although Wittenberg’s production levels were rising, they were still far below Leipzig’s pre-Reformation levels.

Furthermore, the few years before the Diet of Worms were not a period of great growth for the Leipzig industry. When looking at edition totals, Leipzig’s publishing output nearly doubled between 1517 and 1520 to a level that would not be surpassed during the sixteenth century. This is assumed to be the result of the Reformation, as 156 editions by Luther were printed in Leipzig during this period. Multiple Leipzig printers printed the same works by Luther. In 1518, Martin Landsberg, Valentin Schumann, and Melchior I Lotter all printed copies of Luther’s Appellatio. F. Martini Luther ad concilium.23 However, when looking at sheets, the Leipzig industry actually declined during these years. Although there was a large demand for evangelical works, most of those editions were very short, comprised of only a few sheets of paper. 136 of the 156 editions written by Luther and printed in Leipzig between 1518 and 1520 required only a single sheet of paper per copy. They were mostly eight-page quartos. They were also likely to be re-prints of an original Wittenberg edition. Since Wittenberg was so close, the Wittenberg editions might reach the local Leipzig market first. And in addition to the increased demand for Luther’s works, there was also a decrease in demand for more traditional Catholic works, which represented a large segment of the pre-Reformation industry.

One thing is clear, however: Duke George’s ban on printing evangelical works after the imperial Diet was the nail in the coffin for Leipzig. The reason Leipzig’s decline was not as drastic when looking at total sheets was simply because the market had never actually reached such heights and in fact had already begun its decline a few years earlier. Likewise, Wittenberg’s ascendance was tempered by the short nature of Luther’s works. In hindsight, it just seems implausible that a town with only a single press in 1517 would grow to the heights of the Empire’s largest print centre in only two years. Rather, it was a more gradual process, albeit one that was still very impressive. Additionally, the two large drops on the graph in Wittenberg production in 1528 and 1547 when looking at editions were not actually as significant as they appeared. The Capitulation of Wittenberg in 1547 had a far smaller impact. When looking at editions, production fell down to Leipzig’s level, though in terms of press activity, Wittenberg’s sheet totals were still more than double Leipzig’s. Lastly, the Leipzig industry did begin to recover after it turned Protestant in 1539. It even returned to its pre-Reformation levels in some years, a feat hidden when looking at editions. Even though it returned to levels that once made it the largest imperial print city, those levels were now far below what was needed to reclaim the title.

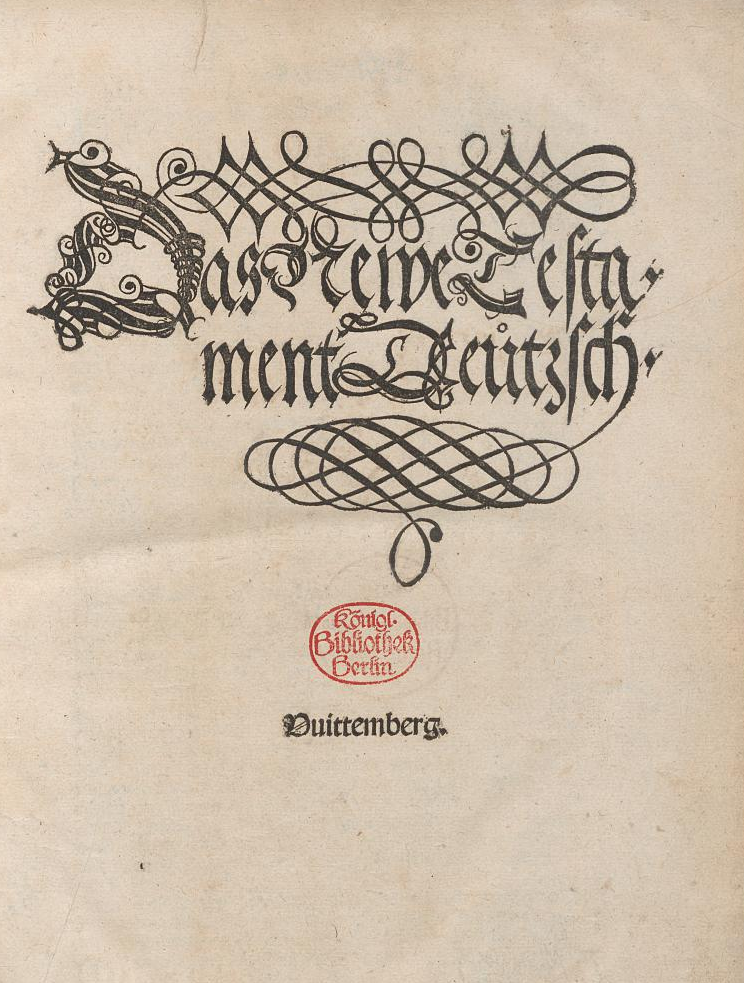

Although Wittenberg’s industry did not grow as quickly as suggested when looking at edition totals, Rhau-Grunenberg’s workshop transformation was still remarkable. Between 1518 and the Diet of Worms in 1521, he was able to match or outproduce most of Leipzig’s printers. As noted, Leipzig’s industry had already started to decline during these years. It was Lotter and Schumann that held up the industry, accounting for nearly 70 per cent of Leipzig’s publications. Again, it was Rhau-Grunenberg versus the combined output of Leipzig’s printers. It was not until other printers arrived in Wittenberg that the industry could surpass Leipzig. That finally happened in 1522 with the publication of Luther’s German translation of the New Testament.24

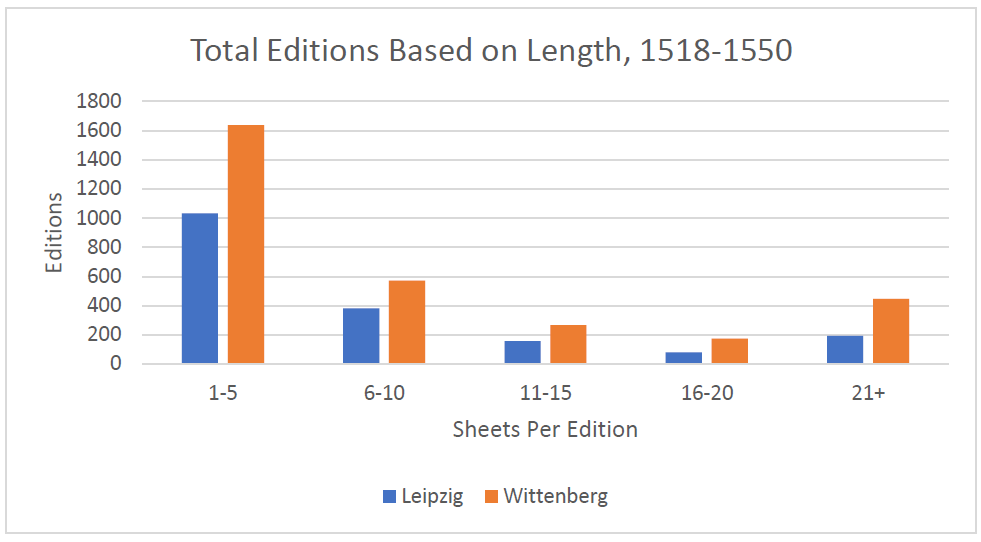

Luther quickly realized the great benefits of brevity: because his writings were short, printers could produce them quickly and cheaply.25 Between 1518 and 1550, over 50 per cent of publications from Wittenberg and Leipzig were books that required five sheets or fewer of paper per copy. However, although the percentage of each city’s industry was similar when it came to small books, Wittenberg’s printers greatly outproduced Leipzig’s.26 Between 1518 and 1550, printers in Wittenberg printed 1,637 editions with five or fewer sheets of paper, compared to Leipzig’s 1,033. Books of this size were a reasonably sized project for printers. Anything more than five sheets of paper, was a more substantial investment and carried greater risk.

Even though such small books represented over half of the editions printed in Leipzig and Wittenberg during this period, their importance in terms of production volume is vastly over represented. In terms of press activity, that is in terms of the sheet totals, small books only represented a small portion of the Leipzig and Wittenberg industries. In Leipzig, small books made up only 12 per cent of press activity. In Wittenberg, it was even less. Less than 9 per cent of press activity was devoted to small books. Both cities were dominated by books on the opposite end of the industry: books requiring more than 20 sheets per edition.

In a city famous for its short Reformation pamphlets, nearly 70 per cent of Wittenberg’s press activity was devoted to books requiring more than 20 sheets of paper. Leipzig was similar with nearly 60 per cent of its press activity devoted to large books. In 1534, the Wittenberg printer Hans Lufft printed Luther’s complete translation of the Bible. For the rest of his career, Lufft focused almost exclusively on Bible printing.27 This is why the number of sheets devoted to large books in Wittenberg was nearly triple that of Leipzig. The focus on large books raises interesting implications about the importance of Reformation pamphlets to the Empire’s printing industry. The Reformation and its pamphlets led to a great increase in the numbers of books being printed across the Empire.28 While this did result in a drastic increase in the number of editions printed, it is clear that those pamphlets were not the items which occupied the printers’ presses. It was the long collections of sermons and Bibles that printers focused on. The most important thing vernacular religious pamphlets did for the Reformation print industry was that it created an appetite for vernacular Bible reading.

Although an analysis of production volumes based on sheet totals overcomes the limitations of relying on edition totals, the methodology is not without its own limitations. What the methodology fails to incorporate is print runs, the number of copies of an edition the printer printed. The sheet total analysis was based on the total number of sheets for a single copy of an edition. It is advantageous because it proportionally represents each book based on its length. But what if a short book was printed in a thousand copies and a long book in only five hundred copies? Is the smaller book being underrepresented? Are the results skewed?

Even if a small book had a print run much larger than average, it still does not compare to the amount of paper needed for a large edition. In 1520 Valentin Schumann printed an edition in Leipzig of Luther’s Ein sermon von dem wucher.29 It was a quarto edition with 30 pages. That results in 3.75 sheets per copy. Due to the way paper was folded, a fraction suggests blank pages at the end. The book probably had 16 leaves, rather than 15. An inspection of the copy at the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek in Munich confirms the last leaf of the gathering is blank. The edition required four sheets of paper per copy. If we estimate a very high print run of 5,000 copies, that results in 20,000 sheets of paper.30 Compare that to Luther’s German translation of the New Testament. The first edition was printed in September 1522.31 The print run was 3,000 copies, an unprecedentedly large run for that period.32 It was a folio edition that had 222 leaves, resulting in 110.5 sheets per copy. Thus, the entire edition required 331,500 sheets of paper. Even when incorporating print runs, the amount of paper needed for smaller projects was only a fraction of the amount necessary for longer works. This conclusion holds even when extending the estimation across all books printed in Wittenberg and Leipzig during this period. The 2,665 editions printed on five sheets of paper or fewer totals 6,687 sheets. Multiplying that by a high print run of 5,000 copies results in 33,435,000 sheets of paper. There were 657 editions printed requiring more than 20 sheets of paper. They total up to 48,092 sheets. Multiplying that by a much lower print run of only 3,000 copies results in 144,276,000 sheets. Not only do the smaller books not surpass the larger books, but they still do not come close. Due to such a high print run estimate, they come closer, but realistically, this number would be much lower.

The same figures can be applied to account for survival bias. Large folios were much more likely to end up in an institutional collection or on private library shelves compared to short pamphlets and thus more likely to have survived to the present day. Luckily, this issue is at least partially mitigated because Luther’s works, even his short ones, were collected from an early time in his movement and often bound together, creating larger volumes, helping improve chances of survival.33 Even when doubling the number of sheets used for items requiring five or fewer sheets per copy to account for books that no longer survive, it fails to affect the main conclusions.

But what if in addition to the size of the book, local practices affected the size of print runs? Perhaps Leipzig’s printers—working in a more experienced and advanced print centre—printed pamphlets in larger print runs than in Wittenberg? If the same calculations as above are recalculated, but with Wittenberg’s print runs for short books reduced to 1,000 copies compared to 2,000 for Leipzig’s, it fails to alter the conclusion. Leipzig’s sheet total would be 12,604,400 compared to Wittenberg’s 25,509,800. So even when assuming Leipzig’s printers are producing twice as many pamphlet copies as Wittenberg’s printers, the original conclusion of Wittenberg’s dominance stands. This is further attested due to that fact that while Leipzig’s printers had to appeal to the Duke to avoid financial ruin, Wittenberg’s top printers became some of the richest men in town and later held high public office.34

The estimations on print runs do not affect the validity of the main sheet total analysis. In the main analysis, Leipzig’s output was equal to 42 per cent of Wittenberg’s output. In the above-mentioned estimation, it was equal to 49 per cent, a marginal difference. Furthermore, the size of the book and its place of production were not the major contributors to determining the size of a print run. The intended audience, the amount of disposable income they could spend on books, and the genre of the literature had a greater influence in determining print runs. Books of the same size, but of different genres could have vastly different print runs. Additionally, print run information rarely survives, and the presence of surviving information is not necessarily a representative figure.35 Since the print runs of the above-mentioned material cannot be proved and that any estimate would have a margin of improbability, the outlined methodology is the safest.36

Circumventing Censorship: Counterfeiting

Because Duke George’s ban against printing Luther’s works devastated the Leipzig printing industry, printers sought help from the town council. They asked Duke George to rethink the ban, but he was not persuaded, and it remained in effect. However, this did not stop printers from printing Luther. From the ban’s implementation until Duke George’s death in 1539, there were 36 editions by Luther printed in Leipzig. Not one identified Leipzig as the place of publication. This was not unusual, as there were no requirements or standardisations in place for publication information. But for Luther’s works printed by Leipzig’s printers, omitting such information hid their involvement in the publication of prohibited works.

Some printers went a step further. Not only did they print evangelical works and omit Leipzig from the publication information, printers also printed false Wittenberg imprints on their title pages. This was not a practice peculiar to Leipzig. Printers in every major print centre in the Empire produced counterfeits of Luther’s works.37 Luther was aware of the practice and warned readers of books that falsely claimed to be from Wittenberg.38 The nineteenth-century bibliographer George Barwick also noted the large variety of typefaces in books with Wittenberg imprints and concluded that they could not be trusted.39 Printers counterfeited Wittenberg books for a number of reasons. In cities where the Reformation had been adopted, such as Erfurt, printing Wittenberg on books helped sell them. Readers wanted books from Wittenberg, as they were guaranteed they had passed through Luther’s hands. In Leipzig, however, printers printed false Wittenberg imprints to circumvent the ban on printing Luther. More than just omitting Leipzig, printing Wittenberg in the imprint further deflected suspicion.

Between 1523 and 1545, Leipzig printers produced 14 counterfeit Wittenberg editions. Four printers participated in this practice: Wolfgang Stöckel, Michael Blum, Jakob Bärwald, and Nikolaus Wolrab. All but two of the counterfeits were printed during Duke George’s lifetime with most being from the 1520s. The earliest is a 1523 edition by Stöckel of Luther’s Ein sermon von der geburt Christi geprediget uff den christag frue vor mittag.40 Stöckel only printed one other Wittenberg counterfeit, a 1525 edition of Luther’s Die Epistel S. Paul an die Galater.41 This is a unique example, as it was a very large book. It was a 472-page octavo, requiring 29.5 sheets of paper per copy. Most Wittenberg counterfeits were of Luther’s pamphlets. Normally, a printer would identify themselves in works of this size, as it allowed them to demonstrate the quality of their work. But in this case, Stöckel sought to hide his involvement in the project, as it was a prohibited book.

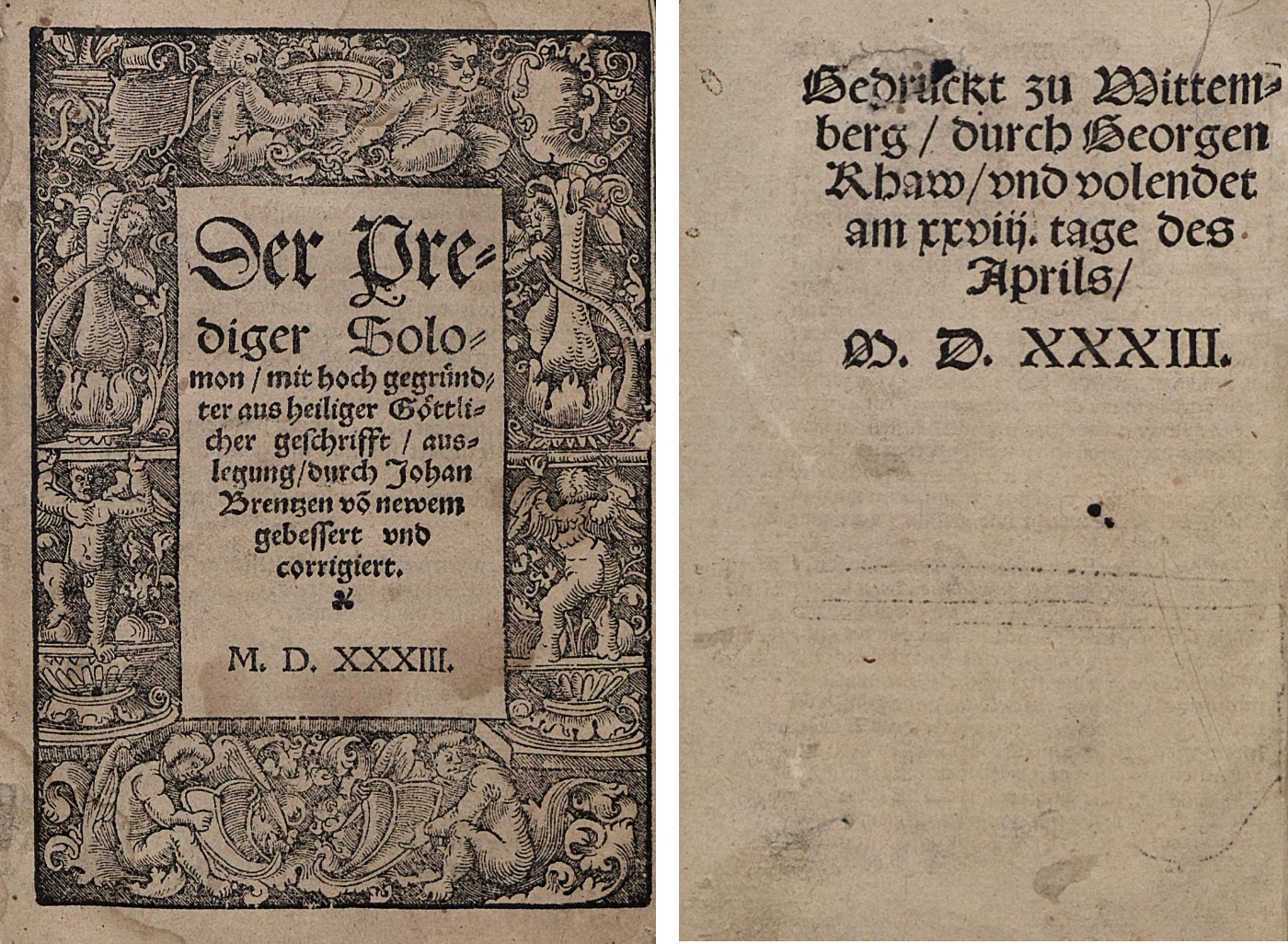

Michael Blum printed most of the counterfeits in Leipzig. Between 1525 and 1533, he printed ten counterfeits. In 1525, he printed an edition of Luther’s Vonn den grewel der stillmesse: so mann den Canon nennet.42 He fooled no one and was imprisoned for three weeks.43 This, though, did not deter him, as he continued the practice. In one of his last counterfeits, a 1533 edition of Luther’s summary of the Psalms, he had the audacity to print his name in the colophon.44 This was not as rare as it may seem. Printers across the Empire would falsely print Wittenberg on the title page, but identify themselves in the colophon. However, it was a risky practice considering his previous incarceration. This example also demonstrates the importance of ambiguity on title pages. For pamphlets during this period, imprints were at the bottom of the title page, often with whitespace between the title or author’s name and the imprint. However, in some cases, there was little space between Luther’s name and Wittenberg. Thus, it is ambiguous whether Wittenberg is acting as a false place of publication or simply meant to identify where Luther was from. At the beginning of Luther’s movement, it was common for printers to refer to him as the ‘Augustiner zu Wittenberg’ or ‘Prediger zu Wittenberg’. But, as his movement grew, and he gained name recognition, this practice was abandoned. By 1533, readers knew where Luther was from. Blum’s usage of Wittenberg was likely as a false imprint. Given that it was an octavo edition with a woodcut title page border, there was very little room for the insertion of movable type. Although ‘Wittenberg’ is ambiguous, it is the only city listed on the title page and only Blum’s name is listed in the colophon. There is no truthful city in the colophon. A reader would only know it was from Leipzig if they knew Blum was from there. In fact, the digital edition of the only known surviving copy of this book, available from the Österreichische Nationalibibliothek in Vienna, identifies the book as ‘Wittenberg: Michael Blum, 1533’.45

Blum’s other counterfeit from 1533 was not a counterfeit of a work by Luther, but rather Johannes Brenz’s Der prediger solonon mit hoch gegruendter aus heiliger Goettlicher geschrifft.46 It does not have a false Wittenberg imprint. The year is the only item in the imprint. The colophon, however, states that it was printed in Wittenberg by Georg Rhau: ‘Gedruckt zu Wittemberg, durch Georgen Rhaw, und volendet am xxviij. tage des Aprils’. Blum’s identity is confirmed by the woodcut title page border, which is surrounded by puti on all sides. There are no examples of Rhau using this border. However, the year before, Blum used it in an edition of a Chronica that clearly identifies himself in the colophon.47

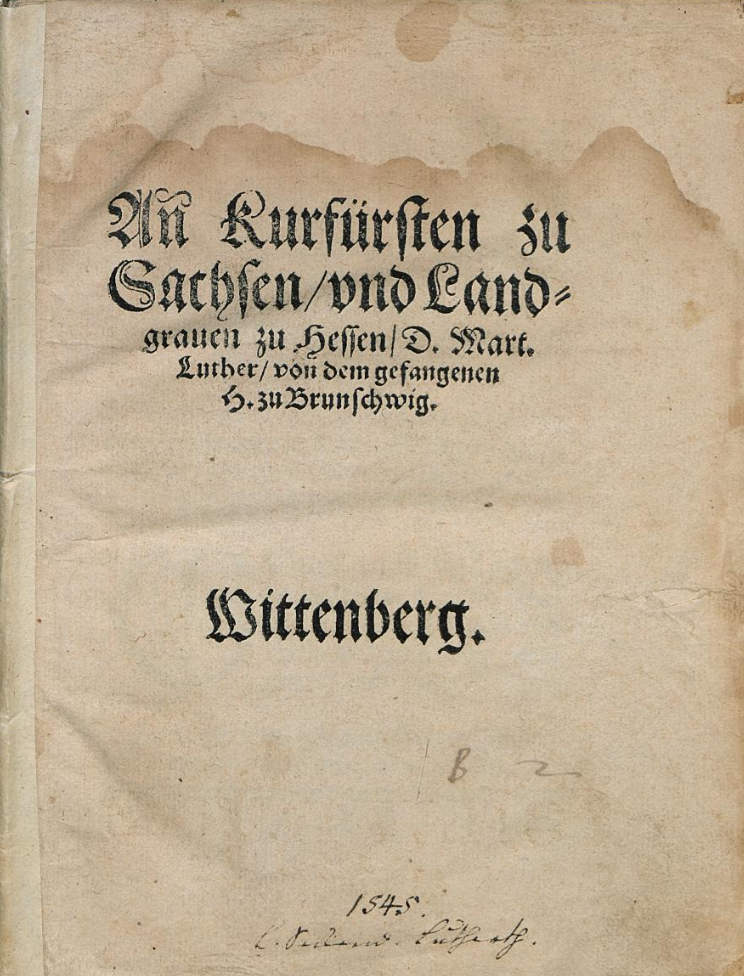

While that was an example of a non-Wittenberg border being falsely attributed to a Wittenberg printer, there are also examples of non-Wittenberg printers copying borders from Wittenberg. Printers in Wittenberg benefited from the talents of Lucas Cranach the Elder, who was court painter to the Saxon elector. His workshop provided woodcut title page borders to local printers.48 These were copied by printers in other cities and often used in combination with false Wittenberg imprints. There is only one case of a border being copied in Leipzig. It is of a quarto border first used in 1530 by the Wittenberg printer Nickel Schirlentz.49 It features Salome on the left holding the head of John the Baptist and the executor on the right with John’s headless body. Schirlentz used this border in 56 editions over the next 17 years. In Leipzig, Nikolaus Wolrab copied this border and used it in a 1542 edition of Savonarola.50 Although this did not have a Wittenberg imprint, Wolrab did use a false imprint on a 1545 edition of Luther’s An Kurfürsten zu Sachsen und Landgraven zu Hessen von dem gefangenen H. zu Brunschwig.51 One printer who is notably absent from the list of printers in Leipzig who produced counterfeits is Melchior Lotter. He ran the city’s most successful print shop. A firm of his size was able to avoid such illicit practices and develop a more successful strategy.

Circumventing Censorship: Branch Offices

Melchior Lotter, Leipzig’s largest printer, began printing independently around 1495. He learned to print in Leipzig as an apprentice to Konrad Kachelofen, whose daughter he married around 1490.52 In his early years he printed many liturgical, academic, humanist, and classical works. He printed many editions of Alexander de Villa Dei’s thirteenth-century Latin grammar, Doctrinale puerorum.53 In his first decade as an independent printer, he printed 13 editions of de Villa Dei, more than any other author. By the time Luther arrived on the scene in 1517, Lotter had more than 20 years’ experience and had printed over 600 editions. Part of that success was his ability to judge what items readers wanted. He quickly started printing Luther, acutely aware of the opportunity. Nearly a third of all editions by Luther printed in Leipzig before the Diet of Worms were printed by Lotter.54 While most were reprints of the originals by Rhau-Grunenberg, Lotter printed the first editions of a few new works by Luther when the single press in Wittenberg could not accommodate the work.55

Luther was impressed by Lotter’s work, especially his nice Schwabach typefaces. Rhau-Grunenberg’s type was older and of an inferior quality. Given the amount of works Luther was writing, there was plenty of room for another printer in Wittenberg. Since Lotter was already well-established in Leipzig, he sent his son, also named Melchior, to set up a branch office. It was a perfect opportunity for the younger Lotter, since Leipzig was already a crowded market, Wittenberg was close by, and he could take advantage of the growing pamphlet market originating with Luther. By December 1519, Lotter had set up shop.

This arrangement turned out to be a brilliant business decision. After the ban on Luther’s works took effect in Leipzig in 1521, Lotter was able to avoid it, as his son could continue printing Luther in Wittenberg, across the border in Electoral Saxony. The elder Lotter was also probably not one to challenge the authority of Duke George since in 1520, he was briefly imprisoned for printing a pro-Lutheran work without first submitting it to the censor for approval.56

Lotter was not the only printer in Leipzig who tried to circumvent the ban on printing Luther’s works by setting up a branch office. Nickel Schmidt tried to move to Wittenberg as a printer, but was unable to establish a shop. Instead he became a bookbinder.57 Valentin Schumann also tried to set up a branch office in Wittenberg, as he already had familial connections there, since his sister married the Wittenberg printer, Josef Klug.58 But the Wittenberg market was becoming too crowded. Instead, in 1522 he set up a branch office in Grimma with Nikolaus Widemar. But it only printed a few works, including some by Luther. The next year, Widemar moved the operation to Eilenburg in partnership with Wolfgang Stöckel.59 Schumann and Stöckel also tried to diversify by moving operations to Dresden.

As if Leipzig had not been hurt enough by the ban on printing Luther, Duke George further damaged the industry by supporting the establishment of a press in Dresden, much nearer his court. The enterprise, led by the Catholic theologian Jerome Emser sought to publish Catholic works in opposition to Luther. To manage the workshop Schumann moved from Leipzig to Dresden in 1524. However, it was not too active, with only about 45 editions over three years. In 1526 Schumann moved back to Leizpig, where he remained for the rest of his career. It was now Stöckel’s turn to work in Dresden, having moved there the same year Schumann returned to Leipzig. Stöckel’s son, Jakob, remained in Leipzig at the helm of his father’s press but he only printed a few editions and shuttered the enterprise in 1529. The elder Stöckel found success by taking over the Emser press in Dresden, printing over 450 editions before his death around 1541.60 His son and grandson continued the enterprise into the seventeenth century. While moving to Dresden did not allow Stöckel to capitalise on printing Luther, it did allow him to continue his business, something that was no longer viable in the shrinking Leipzig market. Although the establishment of a press in Dresden hurt Leipzig’s print industry, it was not a cause of Leipzig’s collapse. Emser’s press was not established in Dresden until 1524, after the collapse of Leipzig’s market. Rather than assisting in Leipzig’s downfall, Dresden provided a lifeboat to Leipzig printers, such as Stöckel, who were abandoning ship in Leipzig. Leipzig’s printers made it clear in their petition to the town council that it was their inability to print Luther’s works that devastated the industry.61 No Leipzig enterprise was able to successfully circumvent the ban on printing Luther as successfully as Melchior Lotter.

Melchior II Lotter set up his press in the workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder, the court painter to the Elector of Saxony. Since the Lotters did not have enough capital to establish a branch office on their own, Cranach and his business partner, Christian Döring, provided the rest. Cranach also owned a paper mill and Döring owned a shipping business, both of which were important for production and distribution. With Cranach’s workshop, paper, and funding and Lotter’s types and expertise, they quickly became a dominant force in evangelical print. Between 1517 and 1521 the elder Lotter printed 50 editions by Luther in Leipzig. After the Diet of Worms, he never printed another work by Luther. His son, however, continued right where his father left off. Between 1522 and 1525 the younger Lotter printed over 75 editions by Luther in Wittenberg. That includes the works by Luther he printed on behalf of Cranach and Döring.62 It does not include, however, Luther’s biblical translations, which took up large amounts of press time.

Printing the German New Testament

After the Diet of Worms, where Luther was declared a heretic and outlaw, he was confined for his own protection in the Elector’s castle near Eisenach. During his captivity, he translated the New Testament into German and gave it to Cranach to publish. Lotter printed it at an incredible speed in an unprecedented 3,000 copies.63 Cranach provided 21 full-page illustrations for the Book of Revelation, some of which depicted the Whore of Babylon wearing a papal tiara. This caused some controversy and the tiara was removed from the second edition, printed only three months later.64

The September New Testament provides a unique case study—in a period regarded for its quick pamphlet production—for determining the speed of Lotter’s press. The New Testament was a folio edition consisting of 221 leaves, meaning each copy required 110.5 sheets of paper. Factoring in the 3,000-copy print run, the entire job required 331,500 sheets of paper, which does not account for sheets ruined by mistake during production. With that total distributed across Lotter’s three presses, the only remaining variable is time. Lotter began printing on 5 May and completed the project on 21 September, a period of 140 days or 120 if Sundays are excluded. But the end date, 21 September, was a Sunday on the Julian calendar. Lotter’s presses might have ran on Sundays as Lotter hurried to finish the project in time for the Leipzig Fair, which began on 29 September.65 The result is somewhere between 789 and 921 sheets per press per day or 33 to 66 sheets per press per hour.66 This speed was vastly improved upon as the second edition was produced in a shorter amount of time and had a 5,000-copy print run.

Applying this rate of production to Luther’s pamphlets demonstrates how much, or rather how little, workshop time Luther’s short, polemical works occupied. In 1521, Lotter printed a quarto edition of Luther’s An den bock zu Leyptzck.67 It was eight-pages long, meaning it required only a single sheet of paper per copy. If you estimate a 1,000-copy print run, it would only take 15 to 30 hours on a single press. Nearly half of all works by Luther that were printed in Wittenberg during his lifetime required only five sheets of paper or fewer per copy. If you estimate a 12-hour work day, which represents 66 sheets per press per hour, and a 1,000-copy print run, that would take a little over 75 hours on a single press. If you use all three presses, it could be done in less than two working days. The brevity of Luther’s writings translated to short production times, which were attractive to printers since they required only a small workshop commitment. It also aided the quick re-prints of Luther’s works in cities across the Empire, helping to spread his evangelical message.

By setting up a branch office in Wittenberg, the Lotter family was able to circumvent the ban on evangelical printing in Leipzig, which took the enterprise to new heights. Melchior I Lotter in Leipzig never printed another Luther work after the ban took effect. It was a risk he did notneed to take. Others however did continue to print Luther, participating in a widespread counterfeiting industry. Some Leipzig printers moved to nearby cities outside the ban’s jurisdiction, but they could not replicate Lotter’s success in Wittenberg. Wolfgang Stöckel, who briefly printed in Wittenberg in 1504, found success in Dresden by embracing the ban and focusing on other streams of revenue. Lotter was so successful in Wittenberg because being in the town with Luther’s oversight was a huge advantage in the early years of the Reformation. It was the larger books, like Luther’s biblical translations, that took up the majority of press time. Although Reformation pamphlets were everywhere, the industry was focused elsewhere. But these large books have often been overshadowed due to the large number of pamphlets in circulation. Studying the movement’s early effects on local industries demonstrates how printers sought to capitalise on the movement and how rulers sought to combat it. In many jurisdictions across the Empire, the ban on printing Luther was not enforced. Duke George demonstrates that rulers could successfully control the printing industry if they chose to strictly enforce local prohibitions. In the process, printers turned to new means to circumvent any measures that disadvantaged them from their peers in other localities.

Figures in this chapter are based on the Universal Short Title Catalogue (USTC).↩︎

Much of this and the following territorial history comes from Helmar Junghans, Wittenberg als Lutherstadt (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht, 1979), p. 44.↩︎

Maria Grossmann, Humanism in Wittenberg, 1485-1517 (Nieuwkoop: De Graaf, 1975), p. 16.↩︎

Hans Volz, ‘Die Arbeitsteilung der Wittenberger Buchdrucker zu Luthers Lebzeiten’, Gutenberg-Jahrbuch, 32 (1957), p. 146.↩︎

For a detailed analysis of Erfurt’s political relationship with Electoral Saxony and the Archbishop of Mainz, see R. W. Scribner, ‘Civic Unity and the Reformation in Erfurt’, Past & Present, no. 66 (February 1, 1975), pp. 29–60.↩︎

Grossman, Humanism in Wittenberg, p. 18.↩︎

Ibid., p. 14.↩︎

Ibid., p. 41. This also benefitted Frederick’s treasury, as the papal endorsement included the right to use income from the local All Saints Church to support the university.↩︎

Junghans, Wittenberg als Lutherstadt, p. 47.↩︎

Grossmann, ‘Wittenberg Printing, Early Sixteenth Century’, Sixteenth Century Essays and Studies, 1 (January 1, 1970), p. 60.↩︎

For the text of this edict, see Heimo Reinitzer, Biblia deutsch: Luthers Bibelübersetzung und ihre Tradition (Wolfenbüttel: Herzog August Bibliothek, 1983), p. 194-95.↩︎

Christoph Reske, Die Buchdrucker des 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts im deutschen Sprachgebiet: Auf der Grundlage des Gleichnamigen Werkes von Josef Benzing (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2007), pp. 556-58.↩︎

The best introduction to pre-Reformation printing in Wittenberg is Maria Grossman’s ‘Wittenberg Printing, Early Sixteenth Century’, Sixteenth Century Essays and Studies, 1 (January 1, 1970), pp. 53-74.↩︎

Andrew Pettegree, Brand Luther: 1517, printing, and the making of the Reformation (New York: Penguin Press, 2015), pp. 10-11.↩︎

Reske, Die Buchdrucker, p. 1078.↩︎

Thomas Lang recently discovered that Simprecht Reinhart also manned a printing press in the Wittenberg castle. However, this was used sparingly and only for official print. For more on this recent discovery see Thomas Lang, ‘Simprecht Reinhart: Formschneider, Maler, Drucker, Bettmeister – Spuren eines Lebens im Schatten von Lucas Cranach d. Ä.’, in Heiner Lück, et al. (eds.), Das ernestinische Wittenberg: Spuren Cranachs in Schloss und Stadt (Petersberg: Michael Imhof Verlag, 2015), pp. 93-138.↩︎

Reske, Die Buchdrucker, p. 1078. Rhau-Grunenberg published two editions of the Resolutiones in 1518 (USTC 690747 & 690748). For Luther’s letter to Spalatin, see WABr I, 190-91. Letters I, 75.↩︎

Felician Gess, ed., Aktenund Briefe zur Kirchenpolitik Herzog Georgs von Sachsen, Volume I: 1517-1524 (Leipzig: Teubner, 1905), p. 641. Quoted in Pettegree, Brand Luther, p. 222.↩︎

Richard G. Cole, ‘The Reformation Pamphlet and Communication Processes’, in Hans-Joachim Köhler (ed.), Flugschriften als Massenmedium der Reformationszeit : Beiträge zum Tübinger Symposion 1980 (Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, 1981), pp. 139–162.↩︎

Mark U. Edwards, Jr., Printing, Propaganda, and Martin Luther (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994).↩︎

Martin Luther, Der sechs und dreyssigist psalm David (Wittenberg: Johann Rhau-Grunenberg, 1521) (USTC 634439).↩︎

Monumenta ordinis minorum (Leipzig: Melchior I Lotter, 1510) (USTC 676422).↩︎

Martin Luther, Appellatio. F. Martini Luther ad concilium (Leipzig, 1518) (USTC 612641 (Landsberg), 612642 (Schumann), 612643 (Schumann), 612644 (Lotter), 612645 (Schumann), and 612646 (Schumann)).↩︎

Das Neue Testament Deutsch (Wittenberg: Melchior II Lotter for Lukas I Cranach & Christian Döring, 1522) (USTC 627911).↩︎

Pettegree, Brand Luther, p. 5.↩︎

From here forward, a small book is considered an edition that required between one and five sheets of paper per copy. At most, this would include a 40-page quarto or an 80-page octavo.↩︎

Drew Thomas, ‘The Industry of Evangelism: Printing for the Reformation in Martin Luther’s Wittenberg’ (University of St Andrews PhD Thesis, 2018).↩︎

Lucien Febvre, Henri-Jean Martin, David Wootton, David Gerard, Geoffrey Nowell-Smith, G. D. Hargreaves, and Jan Hargreaves, The Coming of the Book: The Impact of Printing, 1450-1800 (London: NLB, 1976), pp. 290-294.↩︎

Luther, Ein sermon von dem wucher (Leipzig, Valentin Schumann, 1520) (USTC 647035).↩︎

The 5,000-copy print run is for demonstration purposes only. As pamphlets could be re-printed so quickly, there was much less risk in underestimating demand. It is more likely for printers to use smaller print runs for pamphlets rather than a larger than average print run.↩︎

Das Neue Testament Deutsch (Wittenberg: Melchior II Lotter for Lukas I Cranach & Christian Döring), 1522) (USTC 627911).↩︎

Jane O. Newman, “The Word Made Print: Luther’s 1522 New Testament in an Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Representations, no. 11 (1985): 106.↩︎

Goran Proot details how items bound together were more likely to survive to the present day in ‘Survival Factors of Seventeenth-Century Hand-Press Books Published in the Southern Netherlands: The Importance of Sheet Counts, Sammelbände and the Role of Institutional Collections’, in Flavia Bruni and Andrew Pettegree (eds.), Lost Books: Reconstructing the Print World of Pre-Industrial Europe (Leiden: Brill, 2016), pp. 160-201.↩︎

Wolfgang Mejer, Der Buchdrucker Hans Lufft zu Wittenberg (B. de Graaf, 1965), pp. 6-7. Vicky Rothe, ‘Wittenberger Buchgewerbe und -handel im 16. Jahrhundert’, in Das ernestinische Wittenberg: Die Stadt und ihre Bewohner, vol. 2 (Petersberg: Michael Imhof Verlag, 2013), p. 90.↩︎

Eric Marshall White, ‘A Census of Print Runs for Fifteenth-Century Books’, (CERL, 2012). <https://cerl.org/resources/links_to_other_resources/bibliographical_data#researching_print_runs> (last accessed 11 December 2017).↩︎

Falk Eisermann, ‘Fifty Thousand Veronicas. Print Runs of Broadsheets in the Fifteenth and Early Sixteenth Centuries’, in Andrew Pettegree (ed.), Broadsheets: Single-sheet Publishing in the First Age of Print (Leiden: Brill, 2017), pp. 112-113.↩︎

Drew Thomas, ‘Cashing in on Counterfeits: Fraud in the Reformation Print Industry’, in Shanti Graheli (ed.), Buying and Selling: The Business of Books in Early Modern Europe (Leiden: Brill, forthcoming 2018).↩︎

He mentions this practice in the preface of Auslegunge der Episteln und Evangelien von der heyligen drey Koenige fest bis auff Ostern gebessert (Wittenberg: Josef Klug for Lukas I Cranach & Christian Döring, 1525) (USTC 613951).↩︎

George Frederick Barwick, ‘The Lutheran Press at Wittenberg’, Transactions of the Bibliographical Society, 3, (1896), pp. 9-10.↩︎

Martin Luther, Ein sermon von der geburt Christi geprediget uff den christag frue vor mittag. (Wittenberg [=Leipzig]: Wolfgang Stöckel, 1523) (USTC 646996).↩︎

Luther, Die Epistel S. Paul an die Galater (Wittenberg [=Leipzig]: Wolfgang Stöckel, 1525) (USTC 636593).↩︎

Luther, Vonn dem grewel der stillmesse: so mann den canon nennet (Wittenberg [=Leipzig]: Michael Blum, 1525) (USTC 704211).↩︎

Reske, Die Buchdrucker, p. 561.↩︎

Luther, Summarien uber die psalmen, und ursachen des dolmetschens (Wittenberg [=Leipzig]: Michael Blum, 1533) (USTC 693119).↩︎

Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, 79.L.92.↩︎

Johannes Brenz, Der prediger solonon mit hoch gegruendter aus heiliger Goettlicher geschrifft (Wittenberg [=Leipzig]: Michael Blum, 1533) (USTC 634093).↩︎

Chronica daryn auffs kuertzest werden begriffen die namhafftigsten Geschichten so sich unter allen Keysern von der geburt Christi biss auff das tausent fuenffhundert ein und dreyssigst jar verlauffen haben (Leipzig: Michael Blum, 1532) (USTC 622293).↩︎

Johannes Luther’s collection of Reformation title page borders is the best source for images of Cranach’s woodcut borders: Die Titeleinfassungen der Reformationszeit (Leipzig: Rudolf Haput, 1909).↩︎

Schirlentz first used this border in a 1530 edition of Der Widdertauffer lere und geheimnis (USTC 634764).↩︎

Girolamo Savonarola, Der LXXX. psalm, qui regis Israel intende (Leipzig: Nikolaus Wolrab, 1542) (USTC 633960).↩︎

Luther, An Kurfürsten zu Sachsen und Landgraven zu Hessen von dem gefangenen H. zu Brunschwig (Wittenberg [=Leipzig]: Nikolaus Wolrab, 1545) (USTC 670372).↩︎

Reske, Die Buchdrucker, pp. 556-57.↩︎

The earliest surviving edition is a 1496 edition of the second part. See USTC 742625.↩︎

49 of the 156 editions by Luther printed in Leipzig before 1521 were printed by Lotter. Data from the USTC.↩︎

For example, Luther’s Ad dialogum Silvestri Prieratis de potestate papae responsio. Lotter printed three editions in 1518 (USTC 608851, 608852 & 608853).↩︎

Reske, Die Buchdrucker, p. 557.↩︎

Ibid., p. 560.↩︎

Ibid., p. 1088.↩︎

Pettegree, Brand Luther, p. 223.↩︎

Reske, Die Buchdrucker, p. 176. Figure from the USTC.↩︎

See note 18.↩︎

In Josef Benzing’s Lutherbibliographie and VD16, Lotter is not credited for the items he printed for Cranach and Döring, excluding the September Testament, which VD16 credits to both.↩︎

USTC 627911.↩︎

USTC 627910.↩︎

There is ample evidence that printers worked on Sundays, including Sundays mentioned as the date of conclusion in the colophon. However Curt Bühler asserts many of these cannot not be taken literally. See Curt F. Bühler, ‘False Information in the Colophons of Incunabula’, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 114, no. 5 (October 20, 1970), pp. 398–406. However, Falk Eisermann has noted that some printers would work on such days to beat out a competitor. See Falk Eiserman, ‘Die schwarze Gunst. Buchdruck und Humanismus in Leipzig um 1500’, in Enno Bünz and Franz Fuchs (eds.), Der Humanismus an der Universität Leipzig. Akten des in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Lehrstuhl für Sächsische Landesgeschichte an der Universität Leipzig, der Universitätsbibliothek Leipzig und dem Leipziger Geschichtsverein am 9./10. November 2007 in Leipzig veranstalteten Symposiums (Wiesbaden: Pirckheimer-Jahrbuch, 2009), pp. 149-179.↩︎

The 33-66 sheets per press per hour is based on 140 days to complete the job. It represents a workday between 12 and 24 hours. Thus, in reality, the figure is much closer to 66, which represents a 12-hour workday.↩︎

Luther, An den bock zu Leyptzck (Wittenberg: Melchior II Lotter, 1521) (USTC 632422).↩︎