Selling Luther:

Printing Counterfeits in Reformation Augsburg

This article provides insights into the growth of the Augsburg printing industry during the Protestant Reformation. It highlights the tactics employed by Augsburg’s printers to quickly provide Martin Luther’s works to readers, including the production of counterfeit editions falsely claiming to be printed in Wittenberg. This work also discusses Augsburg’s strategic location, its official policy of neutrality towards the Reformation, and the use of copied woodcut borders from Wittenberg to enhance the authenticity of counterfeit editions. Despite censorship attempts, Augsburg’s printers continued to publish Luther’s works, contributing to the city’s prominence as a printing center during the Reformation.

Notice: This document is a post-peer review author accepted manuscript of Drew B. Thomas, “Selling Luther: Printing Counterfeits in Reformation Augsburg” in Rosamund Oates and Jessica Purdy (eds.), Communities of Print: Books and their Readers in Early Modern Europe (Leiden: Brill, 2022), pp. 17-38. It has been typeset by the author and is for informational purposes only. It is not intended for citation in scholarly work and may differ in content and form from the final published version. Please refer to and cite the final published version, accessible via its DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004470439_003.

In 1514 Jakob Fugger, the patriarch of the wealthy Augsburg banking family, made a loan to Albert of Brandenburg, allowing him to pay for the dispensations required for his appointment as the Archbishop and Elector of Mainz. This made Albert one of the most powerful men in the Empire. Little did the Fuggers know, but this loan would have enormous consequences for the Augsburg printing industry.

In order to repay his debts, the new Elector and Archbishop received permission from Rome to divert a portion of the funds collected from the indulgence campaign intended for the reconstruction of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. It was this very indulgence that riled the Augustinian friar Martin Luther to pen his Ninety-Five Theses against the sale of indulgences, helping ignite the Protestant Reformation, and it was to Albert of Brandenburg that he sent a copy.1 The evangelical movement grew quickly, leading to a surge of printing across the Empire, including in Augsburg, where printers published more pamphlets by Luther than in any other city except Wittenberg.

This chapter briefly examines the growth of the Augsburg print industry in the 1520s and the tactics used to support it. Members of the printing community in Augsburg followed the same strategies as they sought to provide Luther’s works quickly to eager readers. While many printers re-printed Luther’s pamphlets, several in Augsburg and elsewhere went a step further by falsely printing that their pamphlets were printed in Wittenberg, the home of Luther’s movement. This at first might seem like a tactic to evade local censorship prohibitions, but the practice continued even after Augsburg’s ministers joined the evangelical movement. This chapter argues that at a time when humanist communities were increasingly concerned with the origins of their texts, it mattered to readers where their books came from. Books from Wittenberg were important because readers could be assured it represented Luther’s true thoughts. In response, Augsburg’s printers published more counterfeits of Wittenberg books than any other print centre in the Empire and produced them to such a high quality, that no reader browsing a bookstall would suspect the deception. In addition to identifying counterfeits, this chapter will also describe the woodcut title page borders used in Wittenberg that were copied in Augsburg. Several were used by more than one printer, evidence of the business relationships within the printing community. The result is a new understanding of the growth of the Augsburg book industry during the polemical pamphlet campaigns of the 1520s, and the ways in which printers sought to sustain it.

Augsburg’s strategic location just north of the Alps made it an important commercial hub connecting the trade routes between the Italian states and northern Europe. The town was also an important Free Imperial City that hosted several Imperial Diets throughout the sixteenth century. It was during the Diet of 1518 that Martin Luther travelled to Augsburg for questioning by the papal legate Cardinal Thomas Cajetan.2 By 1521, Urbanus Rhegius, the cathedral preacher, was promoting evangelical ideas. In 1525 pastors started marrying and serving communion in both kinds.3 All this despite a riot by the city’s weavers the year before over the city’s banishment of their preacher, Hans Schilling, which ended only after imperial troops arrived to restore peace.4 The city council adopted a neutral policy towards the Reformation. They would tolerate, but not officially endorse, the movement; they would publish, but not strictly enforce, imperial decrees against the Reformation.5 This policy helped the council balance its competing interests. The council did not want to risk revolt among the city’s inhabitants calling for religious reform. However, the city was surrounded by Catholic territories, including the Duchy of Bavaria and Habsburg lands, which it depended upon as its food source and for the trade routes that were so vital to its economy. The city was thus forced to balance internal calls for reform against external pressure to remain faithful to Rome.6 This policy also applied to the city’s printing industry. Censorship was weakly enforced, much to the advantage of the city’s printers. Printing soared during the early years of the Reformation and Augsburg quickly became one of the leading centres for printing Luther’s works.

Reformation Printing in Augsburg

Before the Reformation Augsburg was already a leading centre of print, especially for books in German. Prior to Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses, published in 1517, printers published more than 1,100 German books, the most of any print centre.7 But closer examination reveals that in the years leading to the Reformation, 1501-1517, German books occupied less press time, accounting for 47 percent of publications compared to 58 percent over the entire pre-Reformation period.8 Although this was much more than in other print centres, it must be noted that despite a larger percentage of books printed in Augsburg were in German, Strasbourg’s printers published more German books; they just occupied a smaller percentage of Strasbourg’s total output.9 In comparison, in Leipzig, the Empire’s largest print centre during this period, only 7 percent of publications were in German.

As with several of the Empire’s major print centres, the industry’s pace surged with the rise of interest in the Luther affair. During the first three years of the movement, Augsburg’s printers published more than 400 editions—over 50 percent more than they published in the previous 17 years combined.10 One in three books published in Augsburg between 1518 and 1520 were by Luther, a testament to how quickly he rose to the top of the German book market. Although not having been published in Augsburg until 1518, by 1520 he was the most published author in the history of Augsburg’s printing industry.

This growth only continued throughout the 1520s. The total number of editions printed during this decade would not be matched during the rest of the century. Augsburg’s printers finally surpassed their peers, printing more editions in the 1520s than any other print centre in the Empire. German books were now dominant, accounting for nearly 90 percent of all editions, 97 percent if only looking at Luther’s works. While over a dozen printers were active in Augsburg during the decade, four stood out above the others. Melchior Ramminger, Heinrich Steiner, Philipp Ulhart and Silvan Otmar each published more than two hundred total editions.

Although Augsburg achieved great growth during the 1520s, a different picture emerges when looking at production volumes instead of only analysing edition totals. Production volumes are based on the number of sheets of paper required per book. When looking at edition totals, a Bible and a pamphlet are treated equally, but when looking at total sheets, each book is given its proper weight.11 In terms of editions, Augsburg’s production continues to rise to new heights during the first half of the 1520s. But following the riot by the city’s weavers in 1524 and the Peasants’ War ending in 1525, publishing levels dropped significantly. This was not unique to Augsburg alone, as printing in all Reformation print centres dropped after the end of the polemical pamphlet campaigns.12 But when looking at total sheets production had already begun decreasing during the early 1520s before increasing in 1524 and 1525. Furthermore, although during the 1520s printers published more editions than at any time in Augsburg’s printing history and more than they would at any other time during the sixteenth century, Hans-Jörg Künast has shown that in terms of sheets, printing in the 1520s did not outpace the incunabula period, demonstrating that the early Reformation was not a period of record growth in the Augsburg printing industry.13

Looking at volumes of production also changes perceptions of local competition between printers. In terms of editions, Ramminger and Steiner top the list with over 330 each, but when looking at total sheets, Ramminger is no longer a leading printer. Steiner, however, was by far the most active printer in Augsburg during the 1520s. With a sheet total of over 2,800, he printed at least 40 percent more than his closest competitor, Silvan Otmar. When looking at editions, Otmar printed fewer books than both Ulhart and Ramminger, but in terms of sheets he printed over 80 percent more than his closest competitor. Steiner and Otmar were the two dominant printers in Augsburg.

The enormous growth in the number of editions published in Augsburg during this period was due to the many pamphlets accompanying the religious debates. This was a medium Luther easily adopted and perfected. Printers loved this type of work because they could be printed quickly and cheaply.14 This also made them easier for reprinting in other cities. When Jörg Nadler reprinted Luther’s Sermon on Indulgences and Grace in Augsburg in 1520, it only required one sheet of paper per copy.15 Of the nearly 1,800 total editions printed in Augsburg in the 1520s, over 70 percent were pamphlets.16 In 1522 one in three pamphlets published was by Luther. His preference for writing short works is made apparent by the fact that the average number of sheets per copy required for one of his works was five. In contrast, the average length for a work by Luther’s Catholic foe and fellow opponent at the Leipzig Debate, Johannes Eck, was 16 sheets. As Mark Edwards has noted, it was difficult for Luther’s Catholic opponents to engage in pamphleteering, as it was a genre dominated by vernacular writing, a practice for which they often chastised Luther.17 Of the more than 1,300 pamphlets published in Augsburg in the 1520s, fewer than a hundred were in Latin. And although the average length of one of Luther’s works required only five sheets of paper, 65 percent of his pamphlets required only one or two sheets.

The Reformation was Europe’s first mass-media event. Luther would share his opinions in a pamphlet which was usually printed first in Wittenberg, and then reprinted in several cities throughout the Empire. Because everyone was printing Luther’s works, including more than one printer in the same town printing the same works, it was difficult for a printer to stand out. Why should a reader buy one edition over the other? After all, the texts were the same. Or where they? Authors, including Luther, complained about the poor quality of many publications.18 But readers could be sure of the authenticity of Luther’s works if they knew the edition came from Wittenberg, where it had passed under Luther’s watchful eye. Printers picked up on this at the very beginning of the movement. Before long, pamphlets claiming to have been printed in Wittenberg were appearing throughout the Empire at unprecedented rates.

Printing Counterfeits in Augsburg

The year 1520 was one of Luther’s most active. He wrote three of his most famous works that year: To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation, On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church, and On the Freedom of a Christian.19 It was also the first year of a new phenomenon. In 1520 books appeared on the market claiming to be from Wittenberg. At least nine printers in Augsburg, Basel, Halberstadt, Nuremberg, Strasbourg and Vienna published books with ‘Wittenberg’ in the imprint.

Books with false Wittenberg imprints were printed every year from 1520 until Luther’s death in 1546. Printers in all the major print centres across the Empire produced them.20 Between 1522 and 1524 nearly half of all books with a Wittenberg imprint were counterfeit. With more than 250 counterfeits in circulation, the number of counterfeits nearly matched the entire publication output of Wittenberg during that period. In total, over 70 printers in more than 30 cities used false Wittenberg imprints.21 The southern strongholds of the German printing industry, Strasbourg, Nuremberg and Augsburg, were responsible for more than 50 percent of the counterfeits, of which more than 80 percent were books by Luther. But printers in Augsburg led the way, publishing more than 150 editions with false Wittenberg imprints. This was significantly more than the neighbouring markets, as Nuremberg’s printers published a little more than a hundred counterfeit editions and Strasbourg’s printers published fewer than 60 editions.

Although counterfeit editions of works from Wittenberg were printed throughout the rest of Luther’s life, all but two of the counterfeits from Augsburg were printed during the 1520s. The vast majority, over 80 percent, were printed during the pamphlet campaigns from 1520 to 1524, leading up to the Peasants’ War. This corresponds to the trend for all pamphlets, not just counterfeits. It also highlights that the production of counterfeits was very much a pamphlet phenomenon, accounting for over three quarters of the counterfeits. This also means it was very much a quarto phenomenon, the format most preferred for pamphlets. Only eleven counterfeits in Augsburg were octavos. Although longer works were sometimes adorned with a false Wittenberg imprint, printers rarely omitted their names from larger, more complicated works, which demonstrated their quality and skill.22

Ten printers in Augsburg used false Wittenberg imprints in their works: Heinrich Steiner, Melchior Ramminger, Jörg Nadler, Philipp I Ulhart, Sigmund Grimm, Hans von Erfurt, the heirs of Erhard Oeling, Silvan Otmar, Simprecht Ruff and Johann II Schönsperger. Four of them, Steiner, Ramminger, Nadler and Ulhart, produced over 80 percent of all counterfeits published in Augsburg. Steiner printed 37 editions, Ramminger printed 33, Nadler printed 32 and Ulhart printed 25. The remaining printers all printed six or fewer. Following are brief summaries of the four leading counterfeit printers and examples of counterfeit publications.

Heinrich Steiner

Heinrich Steiner began his printing career as a journeyman for Johann II Schönsperger.23 By 1521 he was operating independently, printing mostly Reformation pamphlets and later classical works.24 Steiner also used several woodcuts in his works and employed many artists, including Hans Burgkmair, Jörg Breu and Hans Schäufelein.25 He is credited with publishing the first emblem book in 1531, which became a popular genre over the following two centuries.26 Ursula Rautenberg called Steiner the “most significant printer of high-quality illustrated and printed Volksbuch”.27 Of the four dozen pamphlets by Luther that Steiner printed, 27 were counterfeits. But although he was one of the most active printers in Augsburg, his career was not without hardship. He was brought before the city council on more than one occasion for censorship violations.28 His debts eventually caught up with him and he was forced to pawn his house, property and printing equipment. In 1547/48 he declared bankruptcy, just prior to his death in March or April 1548.29

Melchior Ramminger

Melchior Ramminger started printing in 1520. Prior to becoming a printer he was listed in the Augsburg tax register as a bookbinder.30 Ramminger printed more pamphlets by Luther than any other printer in Augsburg during the 1520s, printing more than seventy. Following the Augsburg riots of 1524 his production declined, leading him to return to bookbinding.31 It was during the early 1520s that he printed most of his works with false Wittenberg imprints. He printed nearly three dozen, representing just under half of all his works by Luther printed in those years. He died in 1543 and his son Narziß took over his workshop.32

Jörg Nadler

Jörg Nadler was an established printer and bookbinder in Augsburg by the time Steiner and Ramminger set up their presses. Reske states that Nadler’s first print was a Buchlein of Johannes Pfefferkorn printed in 1508, which identifies Nadler in the colophon: ‘getruckt zu Augsprg [sic] durch Jörgen nadler’.33 There are also other works from 1508 that identify Nadler in the colophon along with Wolfgang Aittinger and Erhard Oeglin.34 According to the Universal Short Title Catalogue (USTC) and the German national bibliography (VD16), Nadler printed around 170 editions before he died in 1525. The vast majority of those editions, about 150, were printed during the pamphlet campaigns from 1520 to 1524, suggesting Nadler focused more on bookbinding than printing during his pre-Reformation years. To put into perspective just how much Nadler’s press relied upon Luther, he printed 84 editions by him compared to only five works by Andreas Bodenstein von Karlstadt, the author with the next highest number of editions. Nadler used a false Wittenberg imprint for at least 32 editions, of which all but three were by Luther.

Philipp I Ulhart

Like Steiner, Philipp Ulhart started off as a journeyman in the shop of Johann II Schönsperger.35 His earliest works in the USTC and VD16 date from 1523, a year in which he printed over 40 editions. Like the others, he printed Luther the most. However, Ulhart also printed several Anabaptist works, including a 1527 edition by Hans Hut, an Anabaptist who was later arrested and executed.36 Many of Ulhart’s works by Luther had false Wittenberg imprints. In total, he printed 25 such editions. He kept printing until 1567, the year of his death. He bequeathed a large sum to his heirs and his son, also named Philipp, continued to operate the press for a further 13 years.37

Counterfeit Production

Printers produced counterfeits in several ways. Many used a false Wittenberg imprint on their title pages but printed their name or the true city in the colophon at the end of the book. Although nearly 30 printers published over a hundred editions this way, it was not a popular practice in Augsburg. Only two such editions were printed in Augsburg, both octavo editions printed by Steiner in 1524. The first was a German Psalter translated by Luther. According to VD16 there are copies in Munich and Stuttgart. I have not been able to view the copy in Stuttgart and the copy in Munich has been severely damaged. The title page transcription lists the title as: ‘Der Psal=ter deutsch. Martinus Luther. Wittemberg.’.38 Without seeing the physical title page and the layout of the type, it is unclear whether ‘Wittenberg’ is acting as an imprint or simply identifying where Luther is from.39 Regardless, the colophon identifies both Augsburg as the place of publication and Steiner as the printer. The other edition is a Betbüchlein by Luther.40 It lists Wittenberg and the year at the bottom of the title page and it is not directly following Luther’s name, indicating its role as an imprint. However, the colophon clearly identifies Augsburg as the place of publication and Steiner as the printer. Both of these were longer works, each requiring around twenty sheets of paper per copy. It was thus a larger investment on behalf of Steiner. Including his name in the colophon made sure that he was still given credit for the quality of work.

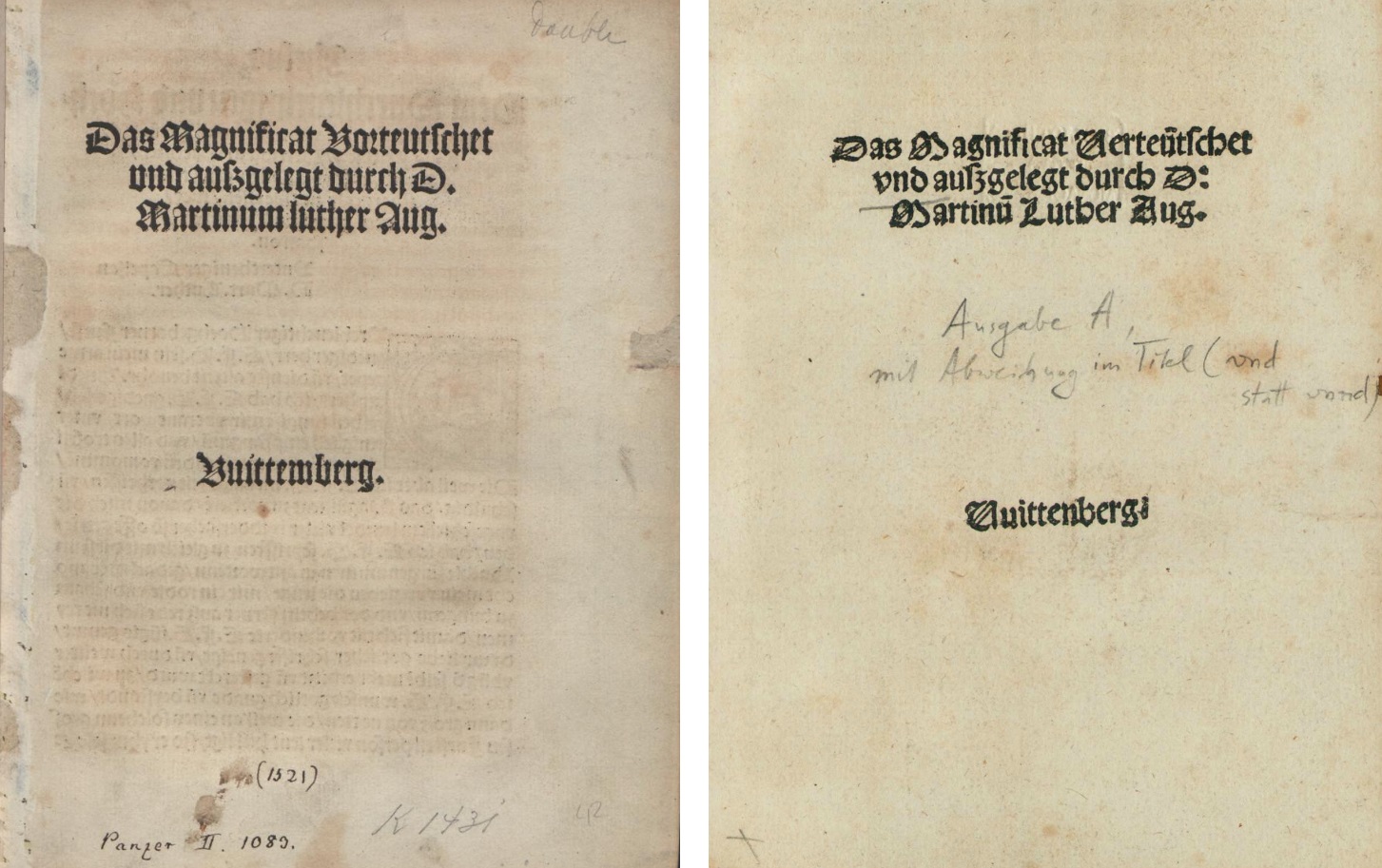

The most popular type of counterfeit in Augsburg were editions that listed ‘Wittenberg’ in the imprint without listing any truthful publication information in the colophon. In 1522 Ramminger published a copy of Luther’s An Earnest Exhortation for All Christians, Warning Them Against Rebellion and Insurrection.41 It has a simple title page with the title arranged in decreasing type sizes. After some whitespace ‘Wittenberg’ is printed in the middle of the page.42 This closely followed the layout of the original Wittenberg edition by Melchior II Lotter.43 An edition with a similar layout was a German edition of the Magnificat published by Jörg Nadler in 1521. It also has the title at the top arranged in a decreasing line width, followed by ‘Wittenberg’ near the middle of the page.44 This re-print also copied the original Wittenberg title page by Lotter, including the same line breaks in the title (See Figure 1).45

(USTC 627728, SBB Berlin, Luth. 1611<ter>; USTC 627722, BSB Munich, Res/4 Th.u. 104,IV,10)

Although many of the early pamphlets from Wittenberg had simple title pages with little or no decoration, they were soon adorned with woodcut title page borders. Printers in Augsburg picked up on this and started decorating their pamphlets with borders as well. In 1524 Ramminger published Luther’s Von kaufszhandlung und wucher.46 It has a short title at the top of the page and at the very bottom an imprint stating ‘Wittemberg. M.D. XXiiij’. The title page is adorned with a floriated woodcut border. In 1522 Steiner published a copy of Von menschen leren zu meyden. The title is at the top of the page and the imprint with ‘Wittenberg’ and the year are in tiny type at the bottom). The title page is also decorated with a single-piece floriated and historiated woodcut border.47

In the previous two examples ‘Wittenberg’ is in a small type that does not stand out on the title pages. However, there are examples where printers clearly sought to falsely promote that these texts were from Wittenberg. In a 1522 pamphlet on relics, Nadler printed ‘Wittenberg’ in the middle with the largest typeface on the page, which combined with the surrounding whitespace, became the focal point.48 In an edition of Luther’s Sermon on the Holy Cross Ramminger decorated the title page with a large woodcut of a crucifix with Mary on the left and Moses on the right. ‘Wittenberg’ is printed on the lower half of the page with the vertical beam of the cross splitting the word in two. It is printed with the largest typeface on the page.49 One last example is another 1522 pamphlet printed by Nadler. The title page includes both a border and a woodblock. Beneath the woodblock, but within the border, ‘Wittenberg’ is printed in very large type.50 Its location at the bottom of the page, separated from all other printed information, leaves no doubt it is meant as an imprint. In many such examples, ‘Wittenberg’ often received more prominence on the title page than Luther’s name. It was not Luther that was unique—everyone printed him. What set these works apart was that they were from ‘Wittenberg’.

On some occasions books from Augsburg had a false Wittenberg colophon. In 1522 the heirs of Erhard Oeglin printed an edition of Luther’s work on Bulla cene domini. There is no imprint on the title page but the colophon states it was printed in Wittenberg: ‘Getruckt zü Wittemberg’.51 In 1520 Jörg Nadler printed an edition of Luther’s Warumb des Bapsts with a false Wittenberg imprint.52 The title page layout is an exact copy of the Wittenberg edition by Johann Rhau-Grunenberg, including the error in the Roman numeral year, printed as ‘D.M.xx.’ instead of ‘M.D.xx.’.53 Nadler copied the line-breaks throughout and even copied the colophon, which also listed Wittenberg as the place of publication. It is clear the compositor had a copy of Rhau-Grunenberg’s edition in hand while setting up the type. This would have sped up production as the compositor did not have to calculate questions of imposition.

A little over 50 of the counterfeits printed in Augsburg were works by authors other than Luther. There were five counterfeit editions by Melanchthon and four by Karlstadt. In 1522, Nadler printed a counterfeit of a work by Johan Eberlin von Günzberg. The title is within a four-piece woodcut border and above an illustration of Christ teaching. There is no space between the title and Eberlin’s name. Beneath the border, ‘Wittenberg’ is printed in letters larger than any other typeface on the page.54 By highlighting Wittenberg on works by authors other than Luther, readers could presume these books dealt with Luther’s evangelical movement. This was similar to the practice at the beginning of the Reformation, when printers often included ‘Wittenberg’ after Luther’s name to indicate the content dealt with the religious affair in Saxony, as he had not yet achieved name-recognition. However, in addition to adding a false Wittenberg imprint in order to attract customers, some printers took the practice a step further. Many printers also targeted the woodcut borders decorating the title pages of Wittenberg books.

Copying the Borders of Lucas Cranach, the Elder

When Martin Luther wrote his Ninety-Five Theses in 1517 there was only one commercial printer in Wittenberg. It was soon apparent that this would not accommodate Luther’s increased literary output. Taking advantage of the situation, the Leipzig printer Melchior Lotter sent his son to Wittenberg where he set up a press in the workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder, court painter to the Elector of Saxony. In addition to creating the woodcut illustrations for Luther’s 1522 German translation of the New Testament, Cranach also created dozens of title page borders for Wittenberg’s printers.55 Because including woodcuts in any project increased production costs, they were traditionally reserved for larger jobs. Using them to adorn Luther’s pamphlets was an innovation. It was the first time woodcut borders were used on such a large scale for such short, cheap items and they soon came to symbolize Reformation pamphlets as printers across the Empire began using them. Many used whatever borders they had on hand, but others specifically commissioned copies of Cranach’s borders and used them for their books with false Wittenberg imprints.

In Augsburg nearly one in five counterfeit editions included a copied woodcut border from Wittenberg. This was more than any other city that produced counterfeits. Moreover, Augsburg’s printers used more copied borders from Wittenberg than any other city. This was largely due to Heinrich Steiner who used at least ten copied borders, evidence of a clear campaign to imitate the pamphlets originating in Wittenberg. The following is an attempt to document at least one instance of each copied border used in editions with false Wittenberg imprints and compare it to its Wittenberg model.56

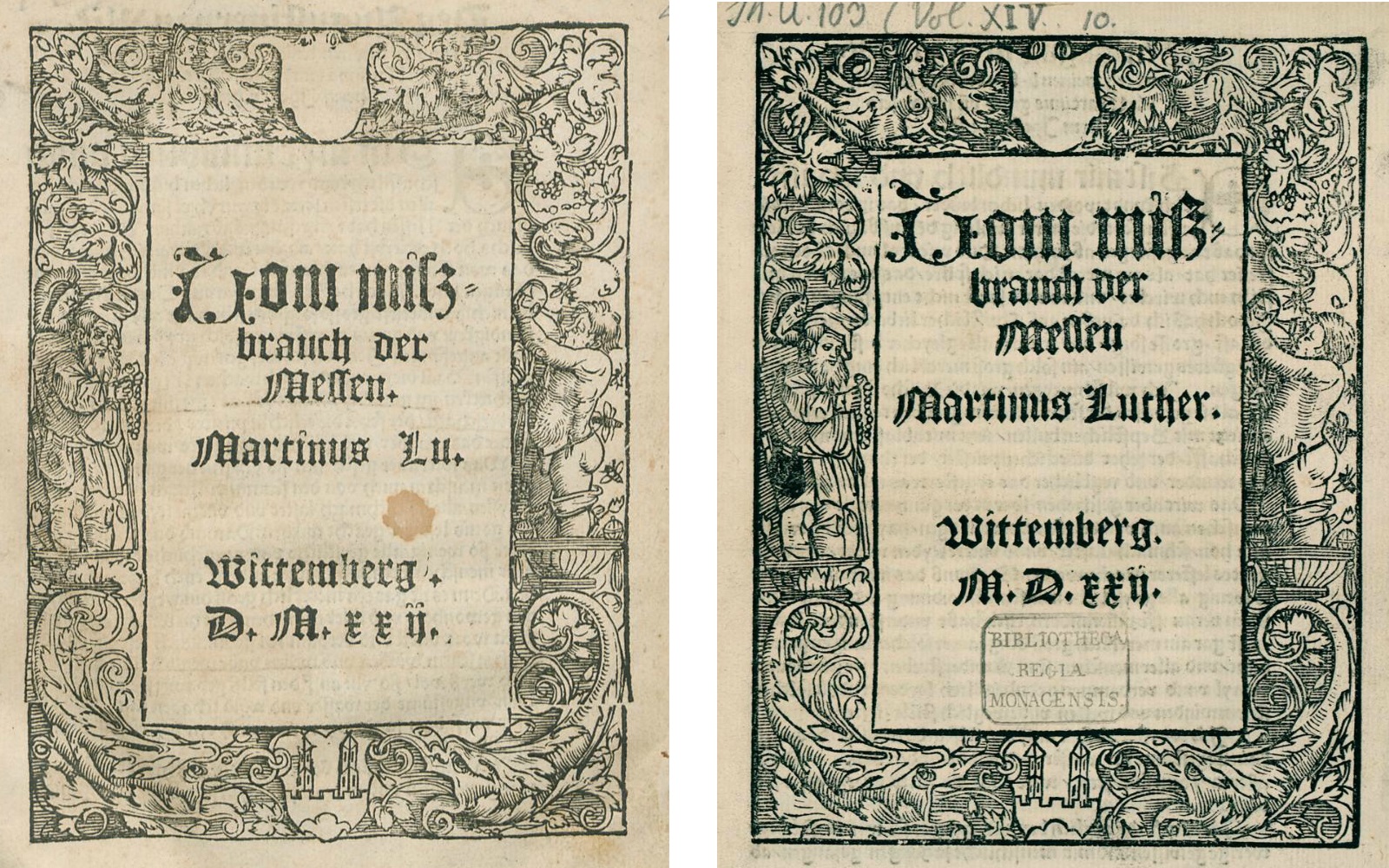

Steiner used copied Wittenberg borders in 13 of his editions with false imprints. The earliest border dates to 1522 in his edition of Vom mißbrauch der Messen.57 The border features Wittenberg’s coat of arms at the bottom and a blank shield at the top, presumably to be filled in by readers with their own, should they have one. This book looks nearly identical to Rhau-Grunenberg’s Wittenberg edition (see Figure 2).58 The layout of the type is nearly the same, however Steiner expanded the abbreviation of Luther’s name and corrected an error in the Roman numeral date. Even the initial used at the beginning of the title is similar. There are very few differences in the borders, but one can spot a difference in the shading of the man’s money purse on the left. Johann Schönsperger also used this border in 1522 for a copy of Luther’s Vom eelichen leben.59 The layout is also a near identical copy of Rhau-Grunenberg’s Wittenberg title page.60 Steiner began his career as one of Schönsperger’s journeyman, so it could be that he received the border from him. According to D. Georg Buchwald’s Luther-Kalendarium, Vom eelichen leben was published at the end of September.61 At the end of the preface of Vom mißbrauch der Messen, Luther states he wrote it on St. Catherine’s Day, which is 25 November. So it could be that the border ended up in Steiner’s shop after first having been used by Schönsperger. To date, I have no evidence Schönsperger ever used it again.

(USTC 700034, Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Sachsen-Anhalt, Ib 3676 a (4); USTC 700033, BSB Munich, Res/4 Th.u. 103,XIV,10)

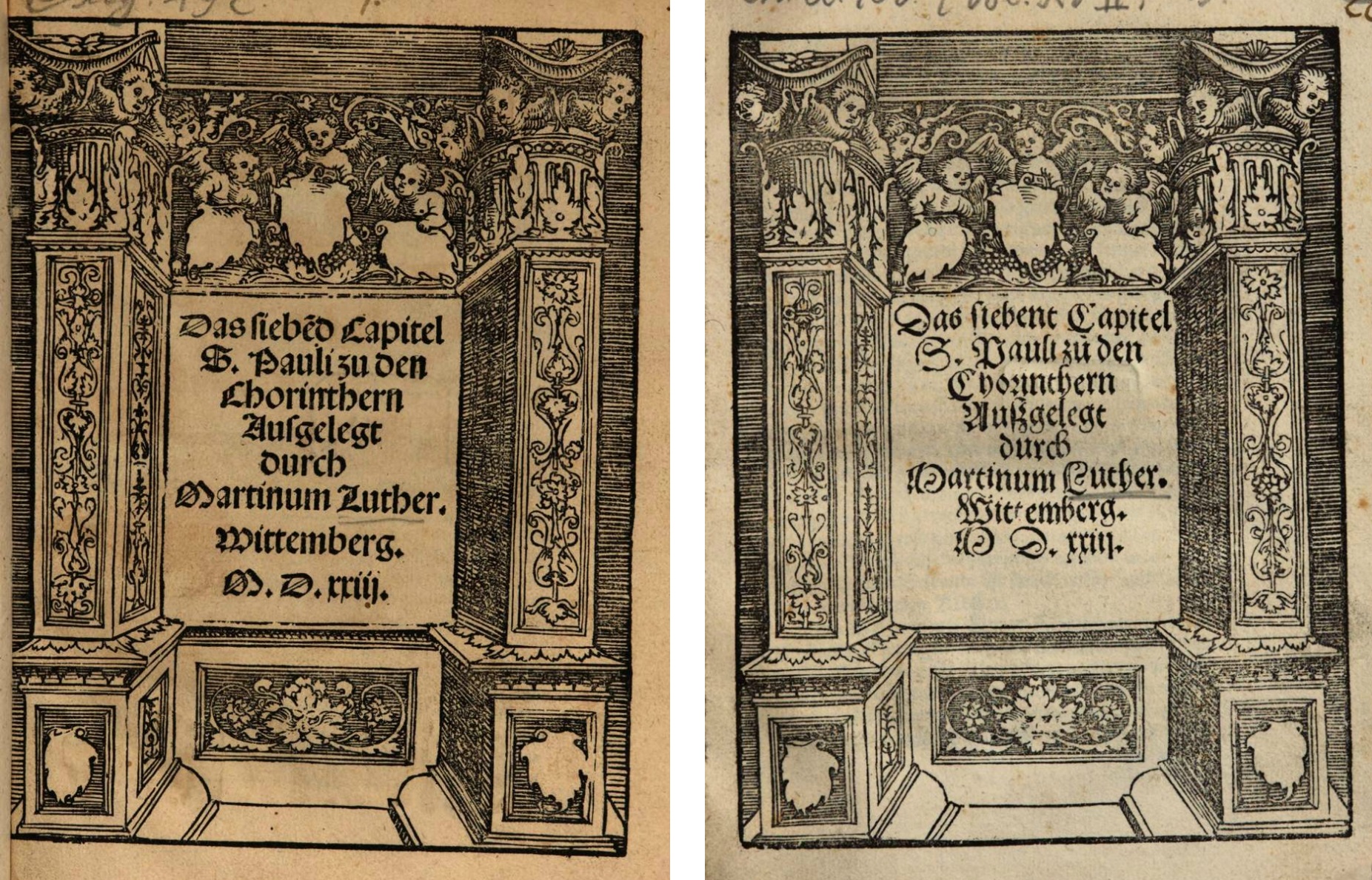

In 1524 Steiner used two more borders copied from the Cranach workshop. In his Das siebent capitel S. Pauli zu den Chorinthern he used a border featuring ornate square columns with angels at the top.62 This was a border used by Melchior Lotter in Wittenberg for at least ten editions, including his edition of the same text (see Figure 3).63 The other border was one featuring a shield with an image of the brazen serpent at the bottom, which would later become a symbol adopted by Philipp Melanchthon. Although the border was first used by Lotter in Wittenberg in 1520, Steiner used it two years later for his edition of a sermon by Luther on the Gospel of Mark.64

(USTC 628020, BSB München, 4 Exeg. 492; USTC 628025, BSB München, Res/4 Th.u. 103,XVII,3)

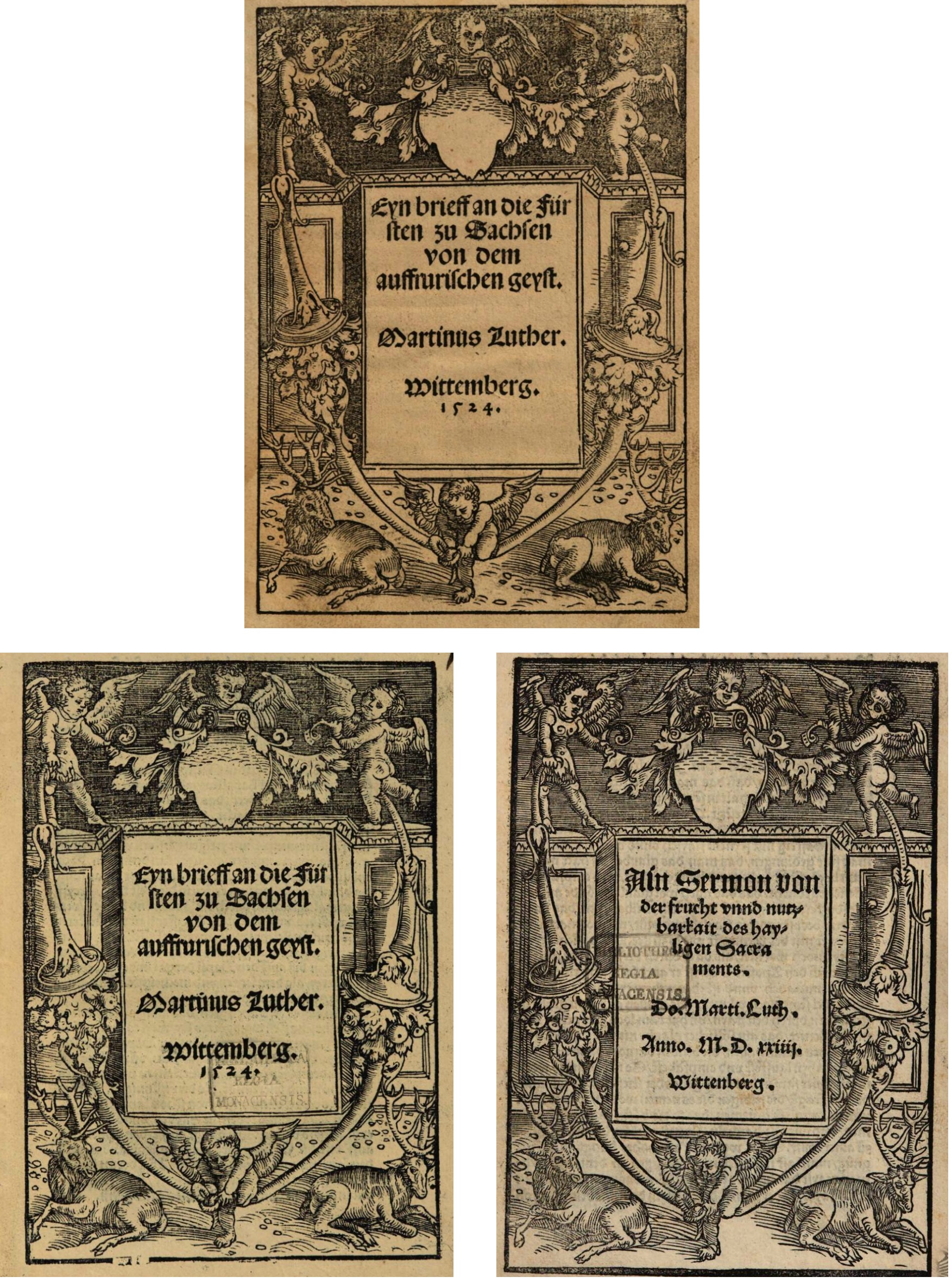

In 1524 Steiner printed a copy of a letter from Luther to the Elector of Saxony. He copied the same border used on the Wittenberg edition, which featured angels and two stags at the bottom.65 The layout of the title page is identical to the Wittenberg edition.66 However, Steiner was not the only printer in Augsburg who copied this border. Philipp Ulhart also used a copy of this border in a counterfeit edition of one of Luther’s sermons on the sacraments. Steiner and Ulhart were not sharing the border, as the two borders have differences, notably, the lack of stones on the ground in Ulhart’s version (see Figure 4).67

(USTC 655865, BSB Munich, H.ref. 748 u; USTC 655866, BSB Munich, Res/4 Th.u. 103,IV,23; USTC 610370, BSB Munich, Res/4 Th.u. 103,XXVI,23)

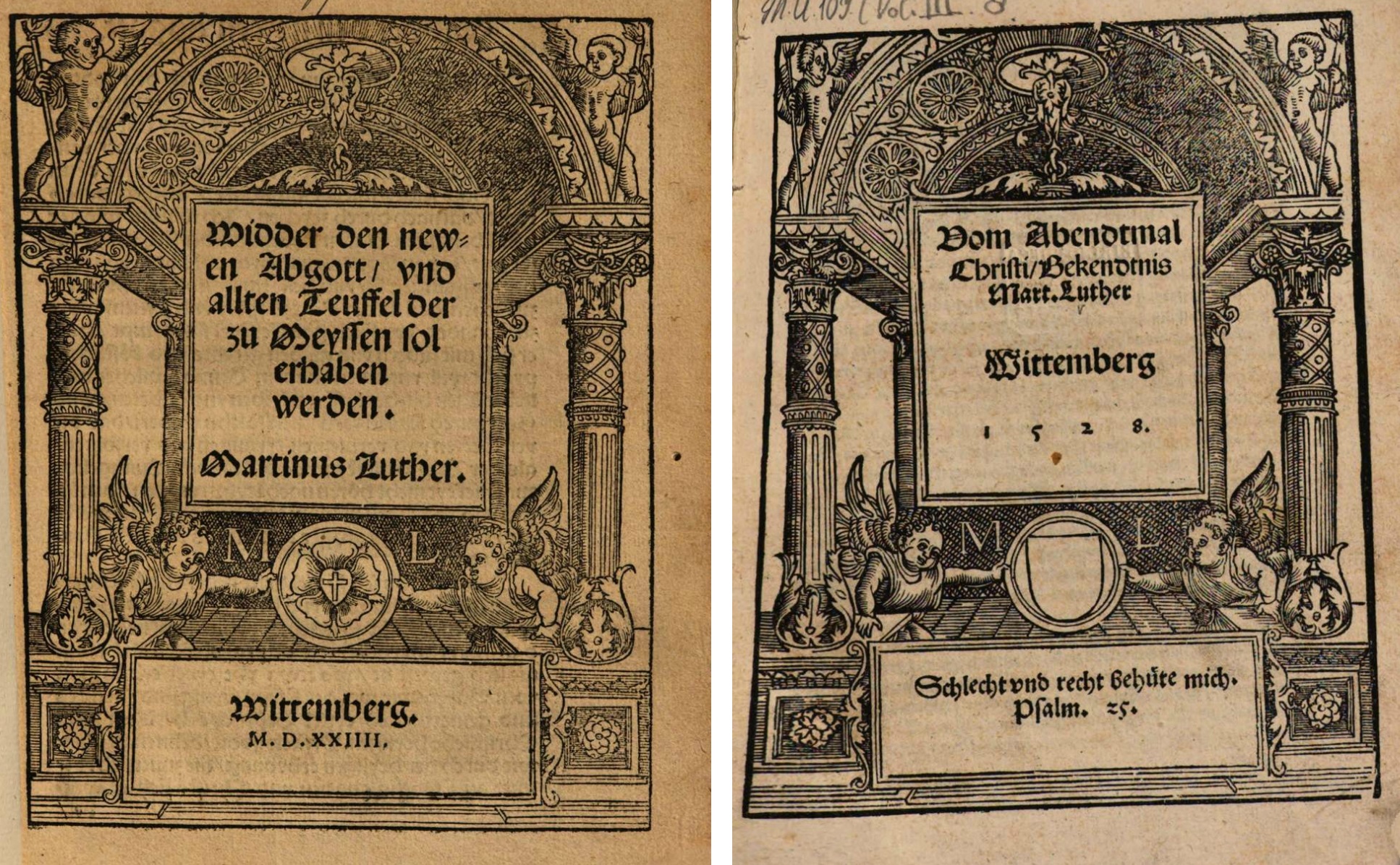

The last two borders Steiner used in counterfeits were in 1527 and 1528 respectively, long after the pamphlet campaigns ended. One was for Luther’s exegesis on Jeremiah.68 The border depicted a faun and his family, a design that was used in Wittenberg as early as 1522 and was still being used when Steiner employed his copy. The last border was a copy of a Wittenberg border depicting the famous ‘Luther rose’. This was the coat of arms granted to Luther by the Saxon Elector. It was incorporated in title pages used in Wittenberg as a mark of authenticity to combat the proliferation of counterfeits.69 It was used in at least 17 editions in Wittenberg between 1526 and 1530. Steiner used it for Luther’s treatise on the Eucharist, Vom Abendtmal Christi bekendtnis.70 The border is identical to the one used in Wittenberg, except instead of the Luther rose, there is a blank shield in its place (see Figure 5). Luther’s initials were still included on either side of the shield. Although Steiner used this border only once, Ulhart used it for at least ten editions with false Wittenberg imprints between 1524 and 1528. As Steiner’s edition was also in 1528, Ulhart either loaned the border to Steiner or Steiner acquired it from Ulhart.71

The last printer in Augsburg who also used a copied border with a false imprint was Jörg Nadler. In a copy of Luther’s Von der beicht ob die der Bapst macht hab zugepieten, he used a border depicting the symbols of the Evangelists in the corners, Peter and Paul at the top and bottom, and the doctors of the Church on the sides.72 Joseph Klug used this border in Wittenberg for at least 17 editions between 1525 and 1540. However, Nadler’s usage predates Klug’s, suggesting earlier unknown uses by Klug or that Klug was copying a border from Steiner. The Klug border is more sophisticated in execution and is a mirror image of the Steiner composition. Silvan Otmar also used a copy of this border in Augsburg, but none have been identified with false imprints. He used his border for five editions during the same time as Steiner. Although the borders are the same composition, they are separate woodcuts, as Otmar’s was a multi-piece border. In one of his editions, he reverses the top and bottom pieces, placing Paul at the top and Peter at the bottom.73

Printers in Augsburg used more copied borders from Wittenberg than any other city. By combining them with false Wittenberg imprints, it would be difficult for a reader browsing a bookstall to recognise that they were not in fact from Wittenberg. This was especially true for the several instances when printers in Augsburg also ensured the layout of the type on the title page was as close to the Wittenberg originals as possible. Many printers tried to reprint Luther’s works quickly in order to get their edition out before the markets were flooded. Copying woodcuts cost precious time. But once they were created, they could be deployed quickly for other editions as well, both counterfeit and non-counterfeit alike.

Conclusion

In July 1520 Pope Leo X issued the papal bull Exsurge Domine, which condemned Luther’s teachings and threatened him with excommunication.74 It also banned the printing or publishing of Luther’s works. However, this was only effective if local authorities enforced the prohibitions. In Wittenberg, Luther burned a copy of the papal bull and the presses kept printing his works. In neighbouring Leipzig, the Duke strictly enforced the prohibitions against evangelical printing, much to the detriment of the local industry.75 Printers in Leipzig resorted to counterfeiting so they could circumvent the prohibitions against printing Luther’s works by hiding their involvement. This was not the case for counterfeits produced in cities accepting of the Reformation, as there were no enforced prohibitions to circumvent. The situation in Augsburg lies between these two extremes. Although Urbanus Rhegius began preaching evangelical ideas in 1521 and priests were getting married and serving communion in both kinds by 1525, the city did not officially adopt the Reformation until 1534.76 As mentioned, Augsburg officials tried to have it both ways by adopting a policy of neutrality. Even before the Diet of Worms, the council was careful not to foment unrest. Johannes Eck wrote to the council demanding they confiscate Luther’s works, but he did not receive a reply.77 Augsburg’s reputation for Reformation printing even reached Rome, as Pope Hadrian VI sent the council a letter in 1522 asking them to enforce the prohibitions.78 The council’s fears of insurrection if they strictly prohibited evangelical ideas were realised during the weaver’s riots of 1524. On 16 October the council published a mandate against possessing or distributing Luther’s writings.79 However, despite this, printers continued publishing Luther’s works. Steiner was taken to court on a few occasions for censorship violations, but he too continued printing evangelical works.80 In the late 1520s, Augsburg’s authorities did arrest and execute a number of Anabaptists. During this time, Ulhart was printing works by the Anabaptist Jakob Dachser. Even though Dachser was imprisoned, this did not deter Ulhart from continuing to print his works.81 One of the authors Ulhart printed was even executed, yet he still printed Anabaptist works.

The council could have strictly enforced the bans if they wanted. After the Schmalkaldic War, when the council was eager to show its support to the Emperor, censorship was strictly enforced. Such a change from past policy caused printers to misjudge and many were punished.82 However, in the 1520s Augsburg’s printers calculated that the risks were worth it and the chance of severe punishment was small. By publishing the mandates against Luther’s writings, the council appeased their Catholic allies, but with its lax enforcement, they supported the local print industry and averted urban unrest. Perhaps then, using false Wittenberg imprints gave Augsburg authorities the opportunity to look the other way. It allowed them to deny that the prohibitions were not being followed. This is unlikely as the council were aware that both Rome and the Emperor knew the bans were not being strictly enforced.83 Besides, this could have been done easily without using a false Wittenberg imprint. Printers could have simply omitted their names and the place of publication, as they did on numerous occasions. Instead, printers made the active decision to keep ‘Wittenberg’ on their title pages. Readers wanted books from Wittenberg and seeking to stand out in a crowded field, Augsburg’s printers gave readers what they wanted.

All images are in the public domain or used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license and attributed in the captions.

Andrew Pettegree, Brand Luther: 1517, Printing, and the Making of the Reformation (New York: Penguin Press, 2015), pp. 73-74. Reinhold Kiermayr, ‘How Much Money Was Actually in the Indulgence Chest?’, The Sixteenth Century Journal, 17, no. 3 (1986), pp. 306-308.↩︎

Daniel Olivier, The Trial of Luther (London: Mowbrays, 1978), pp. 48-53. Bernd Roeck, ‘Rich and Poor in Reformation Augsburg: The City Council, the Fugger Bank and the Formation of a Bi-Confessional Society,’ in Bridget M. Heal and Ole Peter Grell (eds.), The Impact of the European Reformation: Princes, Clergy and People, St Andrews Studies in Reformation History (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2008), p. 69.↩︎

Philip Broadhead, ‘Politics and Expediency in the Augsburg Reformation’, in A. G. Dickens and Peter Newman Brooks (eds.), Reformation Principle and Practice: Essays in Honour of Arthur Geoffrey Dickens (London: Scolar, 1980), p. 55.↩︎

Broadhead, ‘Popular Pressure for Reform in Augsburg, 1524-1534’, in Wolfgang J. Mommsen, Robert Scribner, and Peter Alter (eds.), Stadtbürgertum und Adel in der Reformation: Studien zur Sozialgeschichte der Reformation in England und Deutschland (Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, 1979), pp. 81-83.↩︎

Ibid., p. 81.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Hans-Jörg Künast, ‘Getruckt zu Augspurg’: Buchdruck und Buchhandel in Augsburg zwischen 1468 und 1555 (Walter de Gruyter, 2013). Consult the graph on page 296 for printing in pre-Reformation Augsburg by language.↩︎

The earliest known book printed in Augsburg is from 1468. USTC 743550.↩︎

Between 1501 and 1517 printers in Augsburg printed 346 editions in German (47%) compared to the 432 editions printed by printers in Strasbourg (32%). Data from the USTC.↩︎

Although the beginning of the Reformation is commemorated as having begun in 1517, Luther did not publish his Ninety-Five Theses until the end of October 1517. 1518 was the first full year of Reformation printing.↩︎

To calculate sheet totals, you divide the foliation of a book by its format number. So a quarto with 32 pages (16 leaves) requires four sheets of paper per copy. If it was an octavo, it would require only two sheets. Of the 1,803 editions in the USTC for Augsburg between 1520 and 1529, I was able to calculate sheets totals for 96% of the editions.↩︎

Richard G. Cole, ‘The Reformation Pamphlet and Communication Processes’, in Hans-Joachim Köhler (ed.), Flugschriften als Massenmedium der Reformationszeit : Beiträge zum Tübinger Symposion 1980 (Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, 1981), p. 151.↩︎

Künast, Getruckt zu Augsburg, p. 298.↩︎

Pettegree, Brand Luther, p. 20.↩︎

Luther, Ain sermon von dem ablasz unnd gnade (Augsburg: Jörg Nadler, 1520). USTC 610381.↩︎

For the purposes of this chapter, I am defining a pamphlet as any edition requiring five or fewer sheets of paper per copy. Once you move beyond that the amount of time, money and risk increases for the printer.↩︎

Mark U. Edwards Jr., Printing, Propaganda, and Martin Luther (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), pp. 57-58.↩︎

Jane O. Newman, ‘The Word Made Print: Luther’s 1522 New Testament in an Age of Mechanical Reproduction’, Representations, no. 11 (1985), pp. 102-103. See also Cole, ‘The Reformation pamphlet and communication process’, p. 144.↩︎

Luther, An den Christlichen adel Deutscher nation (Wittenberg: Melchior II Lotter, 1520). USTC 632430, 632433, 632434; De captivitate Babylonica ecclesiae (Wittenberg, Melchior II Lotter, 1520). USTC 629101, 629102; Tractatus de libertate Christiana von der freiheit eines Christenmenschen (Wittenberg: Johann Rhau-Grunenberg, 1520). USTC 651552.↩︎

For an in depth analysis looking beyond the Augsburg industry of the many ways printers produced counterfeits, see Drew B. Thomas, ‘Cashing in on Counterfeits: Fraud in the Reformation Print Industry’, in Shanti Graheli (ed.), Buying and Selling: The Business of Books in Early Modern Europe (Leiden: Brill, 2019), pp. 276-300.↩︎

Ibid., p. 295.↩︎

This is based on observations from ongoing research examining the relationship between sheets and imprints.↩︎

Christoph Reske, Die Buchdrucker des 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts im deutschen Sprachgebiet: auf der Grundlage des gleichnamigen Werkes von Josef Benzing, Beiträge zum Buch- und Bibliothekswesen, v. 51 (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2007), p 34.↩︎

For an example of Steiner’s classical prints, see his 1531 edition of Cicero’s De Officiis (BSB München, 2 A.lat.b. 271; USTC 679342). For more on Steiner’s classical printing, consult Lawrence S. Thompson, ‘German Translations of the Classics between 1450 and 1550’, The Journal of English and Germanic Philology, 42, no. 3 (1943), pp. 343–363.↩︎

Reske, Die Buchdrucker der 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts, p. 34.↩︎

Karl A. E. Enenkel, ‘Illustrations as Commentary and Readers’ Guidance. The Transformation of Cicero’s De Officiis into a German Emblem Book by Johann von Schwarzenberg, Heinrich Steiner, and Christian Egenolff (1517–1520; 1530/1531; 1550)’, in Karl A. E. Enenkel (ed.), Transformations of the Classics via Early Modern Commentaries (Leiden: Brill, 2014), p. 167.↩︎

A Volksbuch is a collection of folktales. See Ursula Rautenberg, ‘New Books for a New Reading Public: Frankfurt “Melusine” Editions from the Press of Gülfferich, Han and Heirs’, in Richard Kirwan and Sophie Mullins (eds.), Specialist Markets in the Early Modern Book World (Leiden: Brill, 2015), p. 90.↩︎

Reske, Die Buchdrucker der 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts, p. 34.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Ibid., p. 35.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Ibid.↩︎

Ibid., p. 31. Johann Pfefferkorn, Ich heyss ain buechlein der Juden peicht (Augsburg: Jörg Nadler, 1508). USTC 668758. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, 20.T.81.↩︎

For example, see Johannes Stamler, Dyalogus. Johannis stamler. Augustn. De diversarum gencium sectis et mundi religionibus (Augsburg: Wolfgang Aittinger, Erhard Oeglin and Jörg Nadler, 1508). USTC 641834.↩︎

Reske, Die Buchdrucker der 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts, p. 36.↩︎

Kat Hill, ‘Anabaptism and the World of Printing in Sixteenth-Century Germany’, Past & Present, 226, no. 1 (February 1, 2015), pp. 79-81.↩︎

Reske, Die Buchdrucker der 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts, pp. 36, 41-42.↩︎

USTC 634177. VD16 B 3280.↩︎

However, given that the work is an octavo with a woodcut title page border, there is usually little space for type. The title, author and imprint usually follow one another with minimal whitespace.↩︎

Luther, Ain betbuechlin und leßbuechlin (Wittenberg [=Augsburg]: Heinrich Steiner, 1524). USTC 609679.↩︎

Luther, Ain trewe Ermanung zu allen Christen. Sich zu verhüten vor auffrür unnd emberung (Wittenberg [=Augsburg]: Melchior Ramminger, 1522). USTC 610433.↩︎

Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Res/4 Th.u. 103,VII,23.↩︎

USTC 656725 and 656726.↩︎

Luther, Das magnificat Uerteütschet vnd auszgelegt (Wittenberg [=Augsburg]: Jörg Nadler, 1521). USTC 627722.↩︎

Luther, Das Magnificat Vorteutschet vnd auszgelegt (Wittenberg: Melchior II Lotter, 1521). USTC 627728.↩︎

Luther, Von kaufszhandlung und wucher (Wittenberg [=Augsburg]: Melchior Ramminger, 1524). USTC 703974.↩︎

Luther, Von menschen leren zu meyden (Wittenberg [=Augsburg]: Heinrich Steiner, 1522). USTC 700162.↩︎

Luther, Ain. Sermon von den hayltumben und gezierd mit üiberfluß vom Hailigen Creütz in den kirchen (Wittenberg [=Augsburg]: Jörg Nadler, 1522). USTC 610484.↩︎

Luther, Ain sermon von dem hayligen Creütz (Wittenberg [=Augsburg]: Melchior Ramminger, 1522). USTC 610267.↩︎

Luther, Ain Christliche und vast wolgegründe beweysung von dem Jüngsten Tag und von seinen zaychen das er auch nit ver meer sein mag (Wittenberg [=Augsburg]: Jörg Nadler, 1522). USTC 609701.↩︎

Luther, Bulla cene domini das ist die bulla vom abentfressen des allerheyligisten Herren des Bapsts verteütscht (Wittenberg [=Augsburg]: heirs of Erhard Oeglin, 1522). USTC 617353. Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, 20.Dd.278. However, the copy at the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, München (Res/4 Th.u. 103,V,3) is assigned to the same VD16 record (K 264) as the copy in Vienna, but it is a different state of the same edition, as it has a false Wittenberg imprint added at the bottom of the title page.↩︎

Luther, Warumb des Bapsts und seyner jungeren bucher (Wittenberg [=Augsburg]: Jörg Nadler, 1520). USTC 706083.↩︎

USTC 706088.↩︎

Johann Eberlin von Günzburg, Ain fraintliche trostliche vermanung an alle frumen christen zu Augspurg am lech darinn auch angezaigt wirt vazu der Doct. Mar. Luther von Got gesant sey (Wittenberg [=Augsburg]: Jörg Nadler, 1522). 609821. Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Cu 1941.↩︎

For examples of Cranach’s illustrations and borders, see: Jutta Strehle (ed.), Cranach im Detail: Buchschmuck Lucas Cranachs des Älteren und seiner Werkstatt (Wittenberg: Drei Kastanien Verlag, 1994).↩︎

Steiner also used borders that were copies of Wittenberg borders for which no instance with a false imprint has been identified.↩︎

Luther, Vom mißbrauch der Messen (Wittenberg [=Augsburg]: Heinrich Steiner, 1522). USTC 700033.↩︎

USTC 700034.↩︎

Luther, Vom eelichen leben (Wittenberg [=Augsburg]: Johann II Schönsperger, 1522). USTC 700025. Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, München, Res/4 Th.u. 103,XII,7.↩︎

USTC 700024. Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, München, Res/4 Polem. 1867 a.↩︎

Georg Buchwald, Luther-Kalendarium (Leipzig: Heinsius, 1929), p. 27.↩︎

Luther, Das siebent capitel S. Pauli zu den Chorinthern (Wittenberg [=Augsburg]: Heinrich Steiner, 1523). USTC 628025.↩︎

USTC 628020.↩︎

Luther, Ein sermon auff das Ewangelion Marci am letsten do die aylf zu tysch Sassen offenbart sich in der Herr Christus und sohalt iren unglauben und irs hertzen hertigkait (Wittenberg [=Augsburg]: Heinrich Steiner, 1522). USTC 646974.↩︎

Luther, Eyn brieff an die Fürsten zu Sachsen von dem auffrurischen geyst (Wittenberg [=Augsburg]: Heinrich Steiner, 1524). USTC 655866.↩︎

USTC 655865.↩︎

Luther, Ain sermon von der frucht unnd nutzbarkait des hayligen Sacraments (Wittenberg [=Augsburg]: Philipp I Ulhart, 1524). USTC 610370.↩︎

Luther, Ain Epistel ausz dem Propheten Jeremia vonn Christus Reich unnd Christlicher freyheit (Wittenberg [=Augsburg]: Heinrich Steiner, 1527). USTC 609790.↩︎

Thomas, ‘Cashing in on Counterfeits’, pp. 289-90.↩︎

Luther, Vom Abendtmal Christi bekendtnis (Wittenberg [=Augsburg]: Heinrich Steiner, 1528). USTC 702195.↩︎

Both the USTC and VD16 infer Steiner as the printer of USTC 702195, but it is unclear why. My suspicion is that the woodcut initial ‘S’ at the beginning of the work belonged to Steiner, but I have been unable to match it to a confirmed edition.↩︎

Luther. Von der beicht ob die der Bapst macht hab zugepieten (Wittenberg [=Augsburg]: Jörg Nadler, 1521). USTC 700119.↩︎

Luther, Ain sermon auf das Evangeli Johannis VI. Mein flaisch ist die recht speiß und mein blut ist das recht tranck etc. (Augsburg: Silvan Otmar, 1523). USTC 610309.↩︎

Leo X, Bulla contra errores Martini Lutheri & sequacium (Rome: Giacomo Mazzocchi, 1520). USTC 837884.↩︎

For an analysis of the collapse of Leipzig’s industry, see Drew B. Thomas, ‘Circumventing Censorship: The Rise and Fall of Reformation Print Centres’, in Alexander S. Wilkinson and Graeme J. Kemp (eds.), Negotiating Conflict and Controversy in the Early Modern Book World (Leiden: Brill, 2019), pp. 13-37.↩︎

Broadhead, ‘Politics and Expediency in the Augsburg Reformation’, pp. 55 and 69.↩︎

Künast, Getruckt zu Augsburg, p. 201.↩︎

Ibid., p. 203.↩︎

Roeck, ‘Rich and Poor in Reformation Augsburg’, p. 71.↩︎

Reske, Die Buchdrucker der 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts, pp. 34-35.↩︎

Hill, ‘Anabaptism and the World of Printing in Sixteenth-Century Germany’, pp. 104-105.↩︎

Michele Zelinsky Hanson, Religious Identity in an Early Reformation Community: Augsburg, 1517 to 1555 (Leiden: Brill, 2009), pp. 150-151.↩︎

On Rome, see Künast, Getruckt zu Augsburg, p. 203. In 1530, the Imperial Diet was in Augsburg. On seeing that the council could not enforce the prohibitions, Charles V offered to send imperial troops. See Broadhead, ‘Popular Pressure for Reform in Augsburg’, pp. 83-84.↩︎