The Lotter Printing Dynasty:

Michael Lotter and Reformation Printing in Magdeburg

This article provides a detailed analysis of the Lotter printing family and their impact on the Reformation movement in Magdeburg. The Lotters were one of the most successful printing dynasties in the early modern Holy Roman Empire, and their workshop in Magdeburg became one of the most active printing houses during the Reformation. This chapter examines Michael Lotter’s printing activity within the local industry from 1528-1556 by looking at volumes of production and investigating printing practices adopted during the Reformation.

Notice: This document is a post-peer review author accepted manuscript of Drew B. Thomas, “The Lotter Printing Dynasty: Michael Lotter and Reformation Printing in Magdeburg” in Elizabeth Dillenburg, Howard Louthan and Drew Thomas (eds.), Print Culture at the Crossroads: The Book in Central Europe(Leiden: Brill, 2021), pp. 245-268. It has been typeset by the author and is for informational purposes only. It is not intended for citation in scholarly work and may differ in content and form from the final published version. Please refer to and cite the final published version, accessible via its DOI: https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004462342_014.

The Lotter family was one of the most successful printing dynasties in the early modern Holy Roman Empire. First established in the fifteenth century, the enterprise overcame the upheaval surrounding Martin Luther’s Protestant Reformation, becoming one of the movement’s most influential printing houses. Although the workshop of Melchior Lotter the Elder, the family’s patriarch, was in Leipzig, where printing Reformation literature was forbidden, he weathered the storm by sending his sons to establish presses in towns friendly to Luther’s cause. In Wittenberg, Melchior Lotter the Younger printed many of Luther’s first editions, including his famous German translation of the New Testament. His typefaces, artwork, and design choices were emulated by Reformation printers throughout the Empire, becoming the de facto Reformation style. Lotter’s younger son, Michael, established a workshop in Magdeburg, where there was less competition.

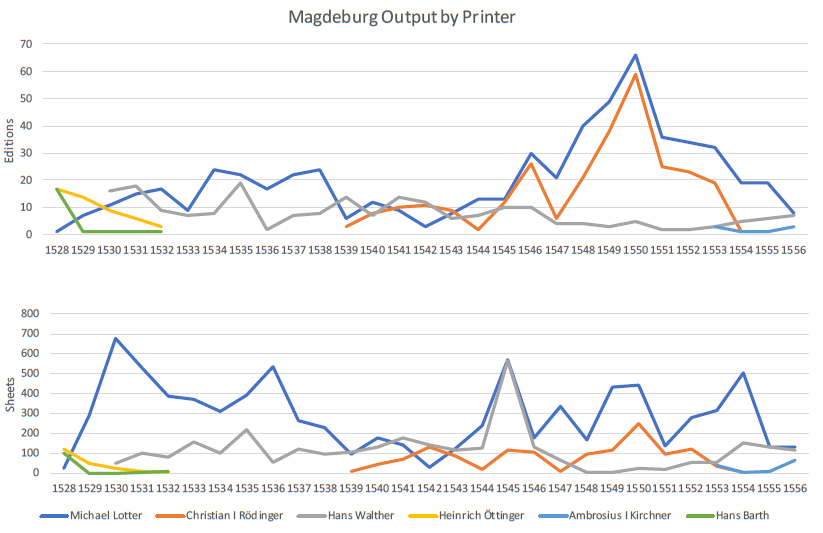

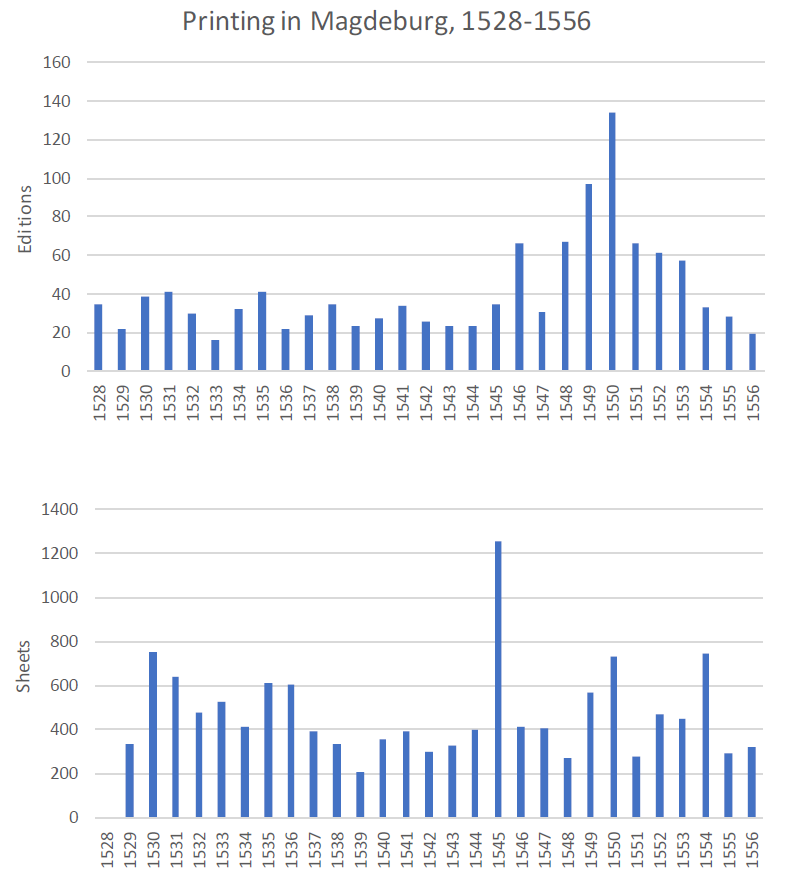

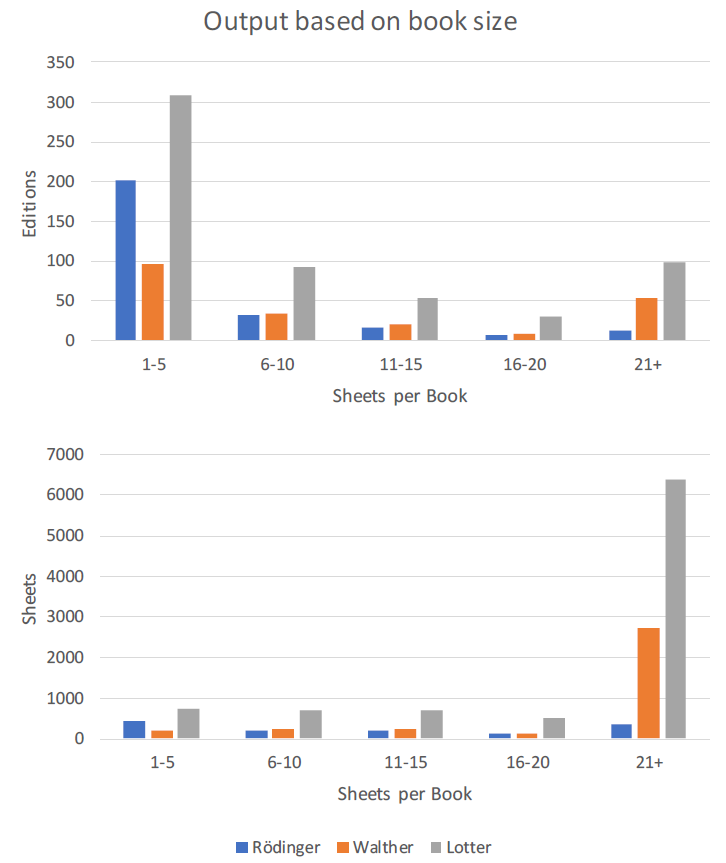

The following research is an analysis of Michael Lotter’s workshop, which is often overshadowed by the work of his father and brother. In Magdeburg Michael became the town’s most active printer. This chapter examines his printing activity within the local industry (1528-1556) by looking at volumes of production. Analysing sheet totals, as opposed to edition totals, provides a more nuanced view of industrial output. Instead of equating a pamphlet to a Bible, looking at sheets gives each its proper weight. I also investigate the printing practices adopted during the Reformation, such as counterfeiting Luther’s works. For this comparison, I created a bibliography of Magdeburg’s printing activity based on the editions in the Universal Short Title Catalogue and the German national bibliography, VD16. Between 1528 and 1556 there were 1,192 editions printed in Magdeburg. In 1550 Magdeburg was besieged by Elector Moritz of Saxony due to the city’s refusal to accept the Augsburg Interim. During the siege, which lasted until 1551, printing skyrocketed as the city’s reformers conducted a pamphlet campaign to garner support. This period has been intensely studied in both English and German.1 These studies, however, limit their focus to the pamphlet campaigns. This chapter seeks to place the pamphlet campaigns within the context of the wider Magdeburg industry and compare it to the years before and after the siege. The result is a new appreciation of the overlooked Lotter, whose heirs would continue printing for the next two hundred years. It also demonstrates that outside the major German print centres, regional industries played an important role in spreading evangelical views, especially by being better suited to adapt to local linguistic variations. As most major print centres were in the south, cities like Magdeburg played an important role in spreading evangelical literature to the northern realms of the Empire and further afield in Central Europe.

The Lotter Family

Melchior Lotter the Elder was born around 1470 in the Saxon town of Aue, not far from Zwickau. Little is known of his early life, but he moved to Leipzig where he became a journeyman in the print shop of Konrad Kachelofen. Kachelofen was one of Leipzig’s first printers, having set up shop in the early 1480s. Around 1490 Lotter married Kachelofen’s daughter, Dorothea, with whom he had three sons, Melchior, a son whose name is unknown, and Michael.2 With the familial connection firmly established, Lotter started playing a more prominent role in the shop. In 1496 both Kachelofen’s and Lotter’s names appear in the colophon of Magnus Hundt’s Expositio Donati secundum viam doctoris sancti: “Impressa Liptzik per Melchiar Lotter. Anno salutis Millesimoquadringentesimo Nonogesimo Sexto. C. K. [=Conrad Kachelofen].”3 However, Lotter began printing on his own as well, with his earliest independent imprints appearing in 1495. In that year he printed an edition of Orationes legatorum Francorum ad Venetos, which clearly lists his name in the colophon.4

Lotter soon established his own shop. He printed many religious and liturgical works, as well as classical and educational books. In 1502 he printed a breviary in both red and black ink.5 The increased complexity due to the multiple ink colours as well as the enormous size of the book (91 sheets of paper per copy) made this an expensive project. But these types of projects were safe investments if there were institutional buyers, such as the church or a school, as that guaranteed a large payment at once instead of having to market and sell each copy individually.

Given that the Church was such a reliable client, it is surprising that Lotter sought to publish Luther’s works. In fact, Lotter had printed confessors’ manuals for the St. Peter’s indulgence which Luther railed against in his Ninety-Five Theses.6 Luther had written them near the end of 1517 and in 1518, Lotter published seventeen editions by Luther, accounting for one in four of his publications that year. The following year, Luther accounted for nearly half of his publications. Luther was impressed by Lotter’s work. There was only one commercial printer in Wittenberg at the time, Johann Rhau-Grunenberg, and he was having trouble keeping up with Luther’s speed. Luther sent many of his works to be printed in Leipzig, as did many other professors at the university in Wittenberg. When Luther visited Leipzig in the summer of 1519 for his famous debate with Johann Eck, he stayed at Lotter’s residence.7 Not long after, Lotter sent his son, the young Melchior, to set up a press in Wittenberg.

This turned out to be was a very smart decision. The following year, after the promulgation of Exsurge domine, the papal bull banning Luther’s works and threatening him with excommunication, Leipzig’s printing industry plummeted. The Duke of Saxony, Prince George, strictly enforced the ban against printing Luther’s works. Lotter the Elder’s production dropped, never to return to his pre-Reformation levels. This mirrored the Leipzig industry as a whole which declined from nearly 200 editions in 1520 to only 25 in 1524. Things got so bad that Leipzig’s printers petitioned the city council to ask the Duke to ease the ban because no one would buy their Catholic works, as everyone wanted Luther.8 Some printers tried to circumvent the ban, but punishment was swift. Michael Blum was imprisoned for three weeks. And Lotter, himself, was imprisoned briefly in 1520.9 However, while his Leipzig shop suffered due to the ban, the branch office in Wittenberg soared.

The senior Lotter was too well-established in Leipzig to move to a small, agrarian town like Wittenberg. Leipzig was a bustling city and home to the famous Leipzig Book Fair. The younger Lotter set up his press in the workshop of the famed Renaissance artist Lucas Cranach the Elder. As court painter to the Elector of Saxony, Cranach was responsible for decorating the many ducal residences of the Elector. However, he started publishing books with his business partner Christian Döring. They also owned a paper mill, supplying Lotter with the necessary supplies for his shop. In 1520, Lotter printed 60 editions in Wittenberg, a third more than his father in Leipzig. Nearly half of these were by Luther. Three were Luther’s very popular and influential On the Papacy at Rome, To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation, and On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church, all of which reveal Luther’s rejection of the papacy.10

Lotter’s most famous publication was in 1522 when he printed Luther’s German translation of the New Testament.11 Luther translated it while confined in the Wartburg after the Diet of Worms where he was declared a heretic and outlaw. The translation was a huge success and Lotter immediately published a second edition. The translation was complemented by woodcut illustrations from the Cranach workshop, including twenty-one full-page illustrations in the book of Revelation.12 It was a hallmark achievement completed in record time. Lotter was prepared for such an ambitious project, as he had experience printing missals and other large books in father’s shop.

Not long after printing the New Testament, the elder Lotter in Leipzig sent his youngest son, Michael, to join his brother. Melchior kept printing independently, but four of the thirty-five editions printed in 1523 included his brother’s name. In an edition of Das Allte Testament deutsch, the colophon clearly states “Melchior vnd Michel Lotther gebruder.”13 However, in 1524 things turned sour. Melchior severely beat an apprentice for reasons that are unclear. He might have been taking out his anger due to a disagreement about his wages with Cranach and Döring.14 Regardless of the reason, the businessmen used it as an opportunity to terminate the relationship. The Lotters were evicted from the premises and set up shop across town. On top of the fine he received from the local authorities, Melchior was no longer receiving the coveted first editions of Luther’s works. With his prospects bleak, he soon returned to Leipzig.

Michael continued the operation, printing many biblical texts over the next few years. In 1526 he printed a folio edition of Luther’s Auslegung der Episteln und Evangelien vom Advent an bis auff Ostern, which was nearly twice as long as the German New Testament. More than half of his works over the following years were by Luther. But by 1528, the marketplace had crowded. When his brother arrived in Wittenberg in 1519, Rhau-Grunenberg was the only competition. By the time Melchior returned to Leipzig, there were seven printers operating in Wittenberg. Michael decided it was best to move elsewhere with less competition and plenty of room for growth. By the end of the year he and his wife, the daughter of Luther’s cousin, packed up and moved downriver to Magdeburg.15

Move to Magdeburg

By the time of Luther’s Reformation, Magdeburg had long been an important ecclesial and commercial centre. Situated on the bank of the Elbe, Magdeburg was the seat of an Archbishopric and a major trade crossroads, making it one of the most important shipping and distribution centres between Dresden and Hamburg. Due to nearby waterfalls and rapids on the Elbe, goods had to be transferred by land before they could continue by river. The city was also a connecting point for trade between the Rhineland to the west and Bohemia to the east. Thus, Magdeburg became an important commercial hub for long distance shipments to all parts of the Empire and beyond and a transfer point for goods being moved from land to water or vice versa. Due to the river, the town was also surrounded by vast, fertile fields resulting in a lucrative grain industry. Confirmed by Imperial decree, any grain passing through territory belonging to the diocese had to pass through Magdeburg’s port, bringing additional riches to the city.16

In addition to its economic importance, Magdeburg was an important Archbishopric, established in the tenth century. Emperor Otto the Great, the first Holy Roman Emperor following the Carolingian Empire, successfully lobbied Pope John XII to establish an Archdiocese in Magdeburg where he kept court and was later buried in the cathedral. Over time this developed into a Prince-Archbishopric with considerable power over Magdeburg and the surrounding territories. Due to this power and influence, many of the princes and dukes in the vicinity sought to have their sons appointed Archbishop, particularly the houses of Wettin in Saxony and Hohenzollern in Brandenburg. Archbishop Ernest II was a member of the House of Wettin and brother to Frederick the Wise, the Elector of Saxony and protector of Martin Luther.17 He was succeeded by Albert of Brandenburg of the House of Hohenzollern, who was also the Archbishop and Elector of Mainz. Albert’s father, and later his brother, was the Elector of Brandenburg. It was Albert’s approval for selling the St. Peter’s indulgence that led Martin Luther to write his famous Ninety-Five Theses and it was to the Archbishop of Magdeburg that Luther sent a copy.18 However, Albert was not resident in Magdeburg but in Halle, following the tradition of his predecessors.

Although the episcopal seat was in Magdeburg, the city had a strained relationship with the Archbishop. While the Archbishop technically had control over the city, the town had won many concessions over the centuries, including the rights to elect a senate, promote their economic independence, and maintain a militia. This power struggle culminated in the murder of Archbishop Burchard III in the fourteenth century.19 This autonomy developed into a set of privileges known as Magdeburg Law that were incorporated into town charters across central Europe.20 Although the town was not a free, imperial city, the records of Imperial Diets were inconsistent, sometimes listing Magdeburg as an episcopal city and other times as a free city.21 During the Reformation the city insisted on its independence, defying the Augsburg Interim, which led to the siege of the city in 1550. This tumultuous time coincided with a flurry of pamphlet activity, raising the local printing industry to new heights. When Lotter moved to Magdeburg nearly two decades prior, the industry was much smaller.

Although Magdeburg’s printing industry was smaller than Leipzig’s or Wittenberg’s when Lotter arrived, its printing history was the oldest of the three towns. Bartholomäus Ghotan’s earliest Magdeburg prints are dated to 1479, a year before Conrad Kachelofen and Martin Brandis started printing in Leipzig.22 Ghotan printed a few dozen editions in Magdeburg before ending his career in Lübeck at the end of the century. Despite the half century of printing in Magdeburg prior to Lotter’s arrival, industry growth was minimal. Only in seven years did production ever reach double digits. In fact, Lotter’s first year in Magdeburg, 1528, coincided with the town’s most active year to that point, with thirty-five editions. That had little to do with Lotter, however, as he only printed one edition in Magdeburg in 1528, not having moved there until later in the year. The only other printers active in the town were Heinrich Öttinger and Hans Barth. Barth was likely one of the reasons Lotter ended up in Magdeburg, as like Lotter, he had tried to set up shop in Wittenberg. But Wittenberg was already too crowded with printers and he instead moved north. When Lotter decided he would likely fair better if he also left Wittenberg, Magdeburg was a logical choice. The city had adopted the Reformation in 1524, shortly after Luther preached in the town.23 It was still close enough to Wittenberg to get copies of Luther’s works to reprint before others did and it was not too far from his father’s workshop in Leipzig.

Michael’s move to Magdeburg in 1528 is confirmed by the colophon in Besweringe der olden duevelschen slangen mit dem goedtliken worde, a popular work by the German judge and reformer Johann Schwarzenburg that had already been printed in Augsburg, Nuremberg, Zwickau and Marburg.24 The colophon states, ‘Gedrücket tho Magdeborch Michael Lotther’. As there are seven surviving editions from 1528 printed by Lotter in Wittenberg, he likely moved in the latter half of the year. In 1529, his first full year in Magdeburg, he only printed half as many editions as Heinrich Öttinger, the leading printer. It was not until three years later in 1532 that Lotter’s production surpassed Öttinger’s. However, the next year both Öttinger and Hans Barth surrendered to the increased competition. Barth relocated again, this time to Roskilde, near Copenhagen and Öttinger’s shop ceased production. So for most of the 1530s, the only printers in town were Lotter and Hans Walther, but they were joined by a new printer, Christian Rödinger, in 1539. Overwhelmingly, evangelical works dominated the industry. During Lotter’s early years in Magdeburg, nearly one in three of the books he printed were by Luther. However, despite being in a new city, Lotter and his peers sometimes falsely printed that their books were from Wittenberg.

Reformation Counterfeiting

It was normal practice in the early modern printing industry to reprint works by other printers without seeking permission. Unless there was a privilege granting a monopoly of a work to a single printer or prohibitions against printing certain items, printers could largely print what they wanted. This was certainly the case with Martin Luther’s writings. Luther’s works were usually first printed in Wittenberg and then quickly reprinted by printers in other cities as soon as they got their hands on the original Wittenberg edition. Josef Benzing’s famous Lutherbibliographie does an excellent job of showing exactly this practice.25 This helped spread Luther’s message across the Empire as it was cheaper and quicker for pamphlets to be reprinted locally rather than shipped long distances.

However, many printers took this practice a step further. Instead of simply reprinting a work by Luther, some printers would keep ‘Wittenberg’ in the imprint on the title page instead of updating it to the truthful city of publication. In 1526, the Augsburg printer Melchior Ramminger reprinted Luther’s sermon on Matthew 22. Beneath the title, but within the woodcut title page border, Ramminger printed “Wittenberg M. D. XXVI.”26 Instead of updating the imprint to state Augsburg, he left Wittenberg. Neither Augsburg nor Ramminger’s name are mentioned in the publication. This was not a limited practice. Printers in every major print centre in the Holy Roman Empire printed counterfeit Wittenberg editions. They produced them in many ways and for different reasons. Some used false Wittenberg imprints to hide their involvement in printing forbidden works. Others, in cities where Luther’s writings were not forbidden, sought to capitalize on Wittenberg’s popularity. Readers wanted books from Wittenberg, knowing they had been produced under Luther’s watchful eye.27

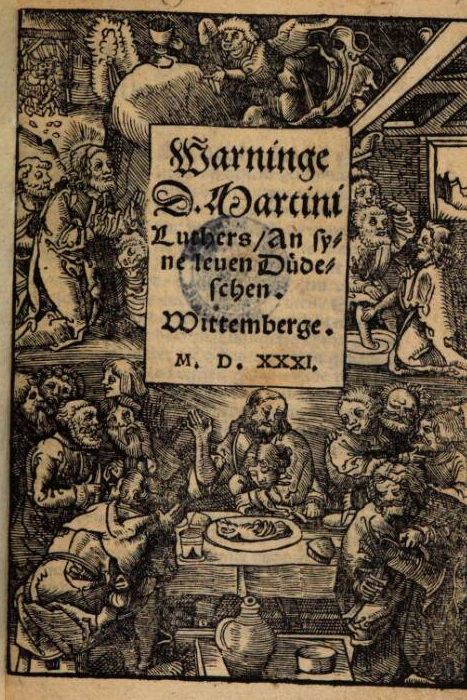

Michael Lotter and his Magdeburg peers were no different. They also printed works with false Wittenberg imprints. Between 1525 and 1546 three dozen editions were printed in Magdeburg with false Wittenberg imprints. All of the leading printers in Magdeburg printed counterfeits, including Lotter, Barth, Öttinger, Rödinger, and Walther. In this practice however, Lotter was the leader, printing over a third of all counterfeits. He published his first false Wittenberg imprint in 1531. It was a Low German translation of Luther’s Warnunge an seine lieben Deudschen, which was printed in five cities that year alone.28 Lotter also used a false Wittenberg imprint in another edition by Luther that year, a copy of Wedder den muecheler tho dresen gedruecket.29

There were many different ways that printers produced their counterfeits. Sometimes they printed a false Wittenberg imprint on the title page but listed their name in the colophon at the end of the book. Of course, if a reader did not know where the printer was from, they would likely assume it was Wittenberg, as it was printed on the title page. This is what Hans Barth did in a pamphlet by Luther that he published in 1528.30 Sometimes, however, the printer would also list the true city of publication in the colophon. In 1527, Barth published a copy of Luther’s Offt me vor dem sterven flegen moege.31 The title page has a false Wittenberg imprint with the year. But in the colophon, the truthful city and printer are listed: ‘Gedrucket tho Mayborg dorch Hans Barth’. The most common practice was simply to print ‘Wittenberg’ on the title page and not include any truthful publication information anywhere within the work. In 1532 Hans Walther printed Luther’s Ein sendbrieff. Widder etliche rottenregister, a short work of only seven leaves.32 It had a large false Wittenberg imprint and no colophon. This type of counterfeit was the most popular in Magdeburg, comprising over half of all produced.

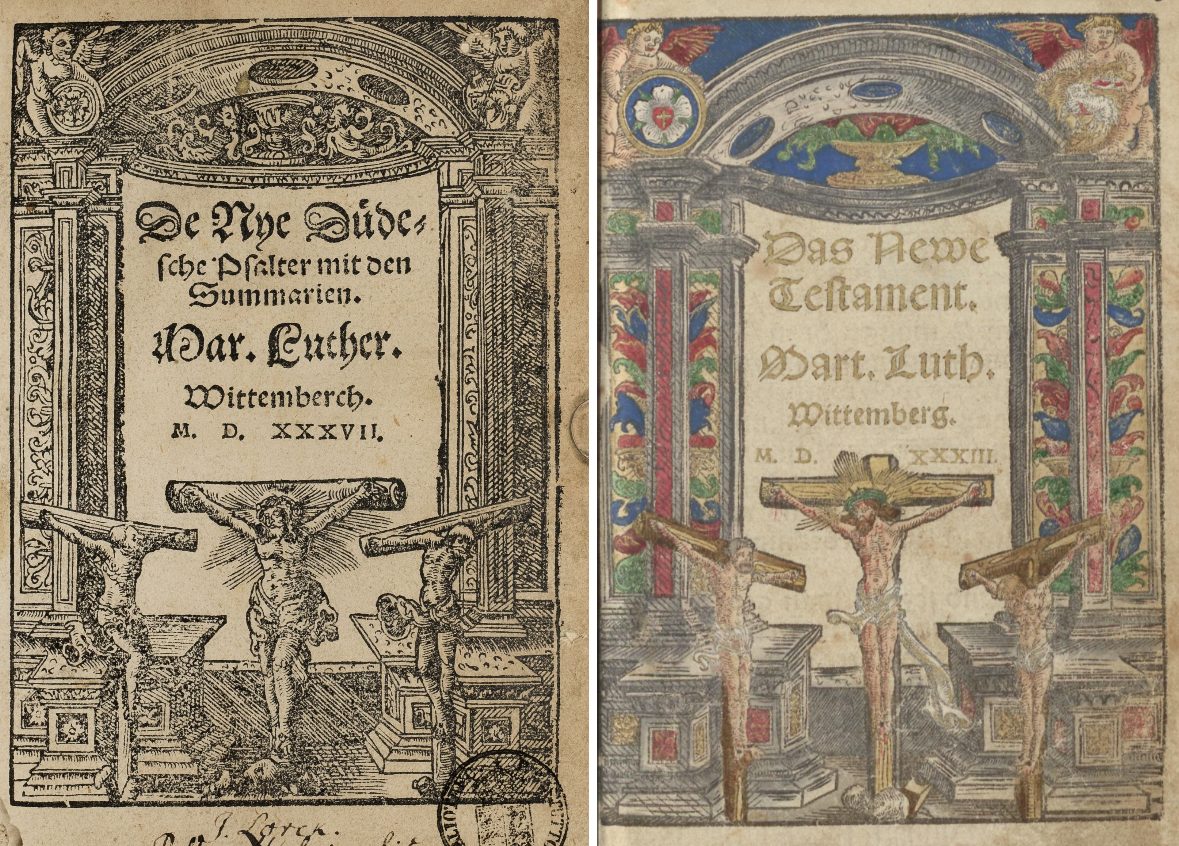

Often printers are identified by finding examples of the same typefaces, ornate initials, or woodcut title page borders used in their non-counterfeit works. But sometimes printers would copy the borders used by printers in Wittenberg to accompany their false imprints. While this practice was common across the Empire, it was rare in Magdeburg. Only three editions used a copy of a Wittenberg border, all by Lotter and all using the same copied border. In 1532 he published a Low German translation of Luther’s New Testament.33 Lotter included a false Wittenberg imprint but also a truthful colophon. In 1537 Lotter used the border again for an edition of the Prophets and for a Low German translation of the Psalter with a summary.34 The woodcut title page border was a copy of a border used by the Wittenberg printer Hans Lufft. It featured square columns on the sides with an arch at the top, Christ and the two thieves crucified at the bottom, and Luther’s white rose at the top left. There are some slight differences between Lufft’s and Lotter’s versions. In Lotter’s border, the Luther rose is a bit smaller and Jesus’ cross is noticeably different at the top. But with a nearly identical border and a Wittenberg imprint, it would be difficult for readers browsing a book stall to know the book was not from Wittenberg.

Although Lotter was participating in a widespread practice by producing Wittenberg counterfeits, his counterfeits differed widely from the norm. Firstly, most of his counterfeits appeared later than those by printers elsewhere. A large majority of the counterfeit Wittenberg editions printed during the Reformation were printed in the 1520s. This coincided with the peak of Luther’s pamphlet activity. Of course Lotter did not arrive in Magdeburg until the end of the decade after the pamphlet wars had subsided.35 This meant Lotter differed in the texts he chose to copy and in the ways he produced them. Although, like his peers, all his counterfeits were works by Luther, unlike his peers, most of his counterfeits were Luther’s translations of scripture. Because Lotter focused on Luther’s biblical translations, these were very long works, requiring substantial investment. The first was a 1531 edition of the Old Testament, Dat ander del des olden Testamentes.36 It was an octavo with 372 leaves, requiring 46.5 sheets of paper per copy. He published the New Testament the following year, which required fifty-four sheets per copy.37 This did not conform to counterfeiting practices elsewhere, as nearly three-quarters of all Wittenberg counterfeits across the Empire required five or fewer sheets per copy.

Larger works were generally not counterfeited because instead of hiding their involvement, printers wanted the credit for their work, as such works gave them the opportunity to show off their skill. That is likely why all of Lotter’s publications of Luther’s biblical translations with false Wittenberg imprints, excluding one, have a full colophon at the end of the book. When browsing the title pages, one might assume it was from Wittenberg, but Lotter was sure to take the credit at the end. However, although his Low German edition of the New Testament was a large project, it is a perfect example of how a printer can save paper by printing in smaller formats. When Lotter’s older brother, Melchior, printed the first edition of Luther’s German translation of the New Testament in 1522, it was a folio edition, requiring 102 sheets of paper per copy.38 This was nearly double what Michael’s octavo edition required. As paper was the most expensive upfront cost in printing a book, this resulted in a large savings in paper, labour, and time.

Nearly all the counterfeits printed in Magdeburg were octavo editions. Other than three quartos by Rödinger and two by Lotter, all the counterfeits were octavos. This is vastly different from the rest of the Empire, where most counterfeits were printed in quarto. Octavos from Magdeburg make up a quarter of all identified octavo counterfeits throughout the Empire. But this was not limited to counterfeits. Octavos accounted for nearly half of all printing in Magdeburg during this period, representing a wider trend across the Empire. During the 1520s, quartos dominated the printing scene, but this was slowly shifting toward smaller formats.

When examining Wittenberg counterfeits, one must take ambiguity into account. In most cases false Wittenberg imprints are easily identified. However, sometimes ‘Wittenberg’ appears on the title page directly under Luther’s name. In many cases it is difficult to determine if ‘Wittenberg’ is acting as the place of publication or simply identifying where Luther is from. Physical inspection of the book is often necessary to see the amount of spacing between the titles, authors, and imprints. Although there is very little space between the title and ‘Wittenberg’ in Lotter’s 1531 edition of Warninge an syne leven düdeschen, Luther’s name is not at the end of the title. ‘Wittenberg’ is clearly acting as an imprint.39 Sometimes there is equal spacing between the title, author, city, and year. Hans Walther published a pamphlet in 1544 that has equal spacing between Luther’s name, ‘Wittenberg’, and the year.40 Although the city and the year are in the traditional location of the imprint at the bottom of the title page, it is ambiguous whether ‘Wittenberg’ was meant to identify the place of publication or simply identify Luther. Many counterfeits published in Magdeburg are ambiguous because they were octavos. Because of their small size, if an octavo has a title page border, there is limited space for type. Often, there is no spacing between the title, author’s name and imprint. Despite this ambiguity, printers still chose to print ‘Wittenberg’ on their title pages and omit ‘Magdeburg’. In nearly every case, Wittenberg is the only city listed on the title page. Even with the ambiguity, if only browsing, readers were certain to associate the books with Wittenberg. But the counterfeits only represented a small segment of the Magdeburg printing industry and none were printed during the pamphlet campaigns surrounding the siege of Magdeburg.

Reassessing the Pamphlet Campaigns, 1548-1552

The biggest moment in Magdeburg’s printing history coincided with the defeat of the Schmalkaldic League in 1547, a year after Luther’s death. With the defeat and capitulation of Wittenberg, many reformers across the Empire, such as Nicholaus Gallus from Regensburg, Matthias Flacius from Wittenberg, Nicholas Amsdorf from Naumberg, and Erasmus Alberus from Wittenberg, fled to Magdeburg, as the city refused to enforce the Augsburg Interim. Magdeburg was placed under the Imperial Ban, and by 1550, Duke Moritz, the new Elector of Saxony, besieged the city. Magdeburg was ready. Over the previous years the city had been storing provisions. Magdeburg was famous for its impenetrable city walls, which were featured on the city’s shield, and were prepared for a long siege. During this time the town’s reformers embarked on a vast pamphleteering campaign to garner up support both locally and further afield. Magdeburg was now the only remaining member of the Schmalkaldic League defying the Emperor and needed support to keep up the fight.

Printing had already started increasing during the Schmalkaldic War in 1546. From 1547 until the siege in 1550, Magdeburg’s printers reached a height not seen again during the sixteenth century.41 In 1547 Lotter and Rödinger together printed only twenty-seven editions. In 1550, they printed nearly five times that amount. Between 1548 and 1550 Magdeburg printed more editions than any other city in the Empire and led the way in printing literature against the Emperor and the Augsburg Interim.42 Over sixty of these books were by Matthias Flacius. He and other reformers provided theological justification to the Senate for their continued defiance.43 Thomas Kaufmann claims that no writer, not even Martin Luther, wrote so much in such a short period of time during the Reformation.44 The pamphlets’ message reached further than the city walls. Duke Moritz banned the pamphlets in his lands to deter his subjects from supporting Magdeburg. He relied on mercenary troops, but at times needed to enlist local soldiers from his territories. However, his estates could accept or reject his request, so it was important for him to influence public opinion.45

The pamphleteering campaign was entirely supported by Lotter and Rödinger. While they published tract after tract, Walther’s output remained in single digits throughout the siege. Lotter and Rödinger often published the same pamphlets at the same time with Lotter printing the Latin version and Rödinger printing the vernacular translation.46 Although the reformers used the pamphlets to provide theological justification to the city’s authorities, the Senate claimed they had no control over the press and thus no responsibility for their content.47 After the siege’s end in 1551, printing dropped substantially, returning to its pre-siege levels. Magdeburg was no longer a centre of Protestant publishing, as many reformers were attracted to Jena where Duke Johann Friedrich, the former Elector of Saxony, founded a university after having lost his claims over Wittenberg. Lotter continued printing in Magdeburg, however, continuing to translate works by Luther, such as a 1554 German edition of the Small Catechism.48 His final editions came off the press in 1556.

The siege pushed Magdeburg’s publishing to the highest it had ever been. However, I would like to reinterpret Magdeburg’s printing industry based on volumes of production instead of focusing on the number of editions printed. This presents the pamphlet campaigns during the siege in a new light and reveals the types of books that occupied printers’ workshops. Instead of looking at edition totals, which makes no distinction between a pamphlet or a Bible, this analysis relies on the total sheets of paper required per copy. A Bible clearly required more paper and occupied more press time than a pamphlet. With this methodology, each book is given its proper weight. To calculate sheet totals you need two pieces of information: the book’s foliation and its format. In 1531 Lotter printed a catechism that was ninety-six pages long, which corresponds to forty-eight leaves.49 As it was an octavo edition, it required six sheets of paper per copy. The year before, he printed Luther’s Auslegung der Episteln und Evangelien, which had a total of 368 leaves.50 As it was a folio edition, it required 184 sheets of paper per copy. Analysing workshop production using this method clearly provides a more nuanced understanding of workshop activity.

There were just under 1,200 editions published in Magdeburg during Lotter’s career from 1528 until 1556. I was able to calculate sheet totals for 1,173 or 98% of the editions. The differences are immediately apparent. In terms of editions, Lotter is the most active printer with nearly 600. Rödinger, the next most active printer printed less than half that amount with 274 editions, followed by Walther with 215. In terms of sheets, Lotter is still the most active printer, but by an even larger margin. Although Lotter printed more than double the number of editions as Rödinger, in terms of sheets, his output is nearly seven times Rödinger’s. Rödinger is no longer the most active printer after Lotter, but rather Walther was, whose production levels were about two-thirds more than Rödinger’s, which makes sense considering he had arrived in Magdeburg a decade before Rödinger.

It is immediately clear that Lotter dominated the Magdeburg market as soon as he arrived. During his first four years, there were three other printers active in Magdeburg and based on editions, it took Lotter that long to surpass them. However, when looking at sheets, Lotter outproduced the others in 1529, his first full year in Magdeburg and dominated the industry over the next decade, often producing more than the other printers combined. One of his first major projects was one he started in Wittenberg. In 1528 he printed Luther’s Auslegung der Episteln und Evangelien, a collection of Luther’s biblical interpretations arranged for the Sundays from Advent to Easter.51 The following year in Magdeburg, he printed the complementary volume, covering the Sundays from Easter to Advent.52 So despite the interruptions to his workshop caused by the move, he was able to immediately return to his normal rates of production.

One reason the pamphlet campaign supporting the city’s defiance of the Augsburg Interim is seen as so influential in the Lutheran debates at the time is because of the great surge in printing in Magdeburg. Both Kaufmann and Rein highlight that it was the most active period during the 16th century for Magdeburg’s printers. Moreover, during the campaign leading up to the siege, Magdeburg’s printers published more editions than any other city in the Empire, a feat they had never done before and would never repeat. The siege lasted from September 1550 until November 1551, but the pamphlet campaign began a few years prior. The Battle of Mühlberg, ending the Schmalkaldic War was on 24 April 1547. This led to the Capitulation of Wittenberg, resulting in Duke Johann Friedrich being stripped of his lands and electoral title. With Wittenberg losing its mantle as the stronghold of Protestantism, Magdeburg became the symbol of resistance, as it refused to implement the Augsburg Interim, which was decreed by Emperor Charles V at the Imperial Diet on 15 May 1548.

Magdeburg was the only major print centre in the Empire still publishing literature against the decree.53 Kaufman states that no other city in the Empire printed more books than Magdeburg during the years 1549 and 1550 and that the five years surrounding the siege represent a quarter of all publishing in Magdeburg during the 16th century.54 If we place this flurry of pamphlet activity within the wider context of the Magdeburg printing industry by looking at production volumes, it is clear that its importance has been over emphasized. In terms of sheets, 1549 and 1550 were not the most productive years. Neither year falls in the top three years of production between 1528 and 1556. The year 1545 was the greatest year in Magdeburg’s print history by far, as printers printed 70% more than they did in 1550, the largest year during the pamphlet campaign. In 1545 all three of the main printers published large books. Lotter printed the Cantiones ecclesiasticae latinae and a Low German translation of the Luther’s Hauspostils, Walther printed a Low German translation of the complete Bible, and Rödinger printed a Low German translation of Johann Spangenberg’s Auslegung.55 Furthermore, in terms of sheets Magdeburg was not the largest print centre in the Empire in 1549 and 1550. Although Magdeburg’s printers published more editions than any other city, Wittenberg was still the Empire’s largest print centre in those years, producing 200% and 300% more than Magdeburg’s presses respectively.56

Rather than a great increase in printing, Magdeburg’s production levels dropped during the siege. In 1551, the year encompassing the majority of the siege, Magdeburg’s presses had one of their lowest years in two decades. Because the edition totals were so high and the sheet totals much lower, it suggests that the pamphlet campaigns dominated the presses during these years. In 1548 printers printed more than double the number of editions from the previous year. However, when looking at sheets, 1548 actually saw a drop in production. This was also the year printers began publishing Matthias Flacius’ work. He was an exile from Wittenberg who became one of Luther’s most prominent defenders.57 Eight of his editions were published in 1548 followed by 25 more in 1549. These were often very short works, requiring only a few sheets of paper per copy. Such items could be printed quickly and cheaply by printers. This meant they could also be reprinted quickly if the first run proved popular.

Between 1548 and the end of the siege, a third of publications required only five or fewer sheets of paper per copy. This was much higher than the previous decades when such items often represented less than 10% of all activity. Lotter and Rödinger were the two printers that dominated the pamphlet campaigns. In 1550, when the number of editions peaked, Lotter’s and Rödinger’s outputs were nearly equal with 66 and 59 editions respectively. But in terms of sheets, Lotter printed nearly twice as much as Rödinger, despite this being the most successful year during Rödinger’s career in Magdeburg. That is because Lotter did not only focus on pamphlets, he also continued printing larger books, such as a 1549 edition of Spangenberg’s Postilla duedesch.58 Because 80% of Lotter’s and Rödinger’s editions between 1548 and 1552 required only five or fewer sheets of paper per copy, one would assume pamphlets were the focus. However, in terms of sheets, Lotter was concentrated on larger books. Although only 6% of his editions were for books requiring more than twenty sheets, those 14 editions encompassed nearly 40% of his output.

The quick decline in printing after the siege coincided with the end of the pamphlet campaigns. In every successive year from the end of the siege in 1551 until 1556, the last year of Lotter’s career, the number of editions fell. This gives the impression that printing before the siege was low and afterword it returned to its low levels. But in terms of sheets, printing actually increased after the siege. From 1551 to 1552, there was a 70% increase in production. In 1554 production rose higher than in 1550, which was the most active year during the pamphlet campaigns. Lotter dominated production that year due to his publication of a Low German edition of the complete Bible.59 That single edition, a folio requiring 411.5 sheets of paper per copy, represented over 80% of his workshop output for the year. It was the following year when Magdeburg’s production volumes began declining, partly due to Rödinger’s move to Jena in 1554.

The patterns of Lotter’s workshop during the siege and pamphlet campaigns correspond to the rest of his career. Although more than half of all books Lotter printed in Magdeburg throughout his career required only five or fewer sheets of paper per copy, those 309 editions represent only 8% of his workshop activity. It was the Bibles, Auslegungen, and other large books—in Latin, Low German, and High German—that occupied the majority of press time. Books requiring more than twenty sheets per copy represent more than 70% of the sheet totals, yet only 17% of the editions.60

This focus on larger projects made Lotter not only the most active printer in Magdeburg, but also one of the most active printers in the Holy Roman Empire. He left Wittenberg because the market had become too crowded. However, once he was able to thrive in Magdeburg, his production levels surpassed all of the printers in Wittenberg, except for Hans Lufft, the printer of Luther’s complete German Bible.61 Compared to the Empire’s most active printers between 1518 and 1550, Lotter ranks sixth with a total of more than 9,000 sheets.62 With less competition in Magdeburg and a large market for Low German evangelical literature, he was able to become one of the most important printers of the Reformation.

In 1556 Lotter printed his last books. They were mostly small projects, except for two editions by the reformer Veit Dietrich that he printed for a client in Lübeck. Throughout his more than thirty years in the industry, he printed over 600 editions. His presses would not stay silent, however, as his son-in-law and long-time assistant, Ambrosius Kirchner, took over his workshop. In a sign of what was to come, both Lotter’s and Kirchner’s names appear in the colophon of a Low German translation of the Apocrypha published in 1555.63 The enterprise continued in the family for the next two hundred years, passing through seven generations. Little did Melchior Lotter the Elder know when he began printing in Leipzig in the fifteenth century that his family would still be printing in the eighteenth century.

Although his father and older brother often overshadow him in scholarly literature, this chapter demonstrates that Michael Lotter transformed his brother’s faltering enterprise into one of the Empire’s most active offices. Free from the fierce competition in Wittenberg, he quickly re-printed Luther’s works for a north German audience. Due to the linguistic differences in the northern Empire, his Low German translations were bought up by an eager public seeking evangelical literature. This set Magdeburg apart as the reprints of Luther’s works from other cities had to be shipped further to reach this market and were not in the local tongue. Magdeburg quickly became the most northerly city of the Empire’s major centres of print and dominated the region.

The sheet totals methodology implemented in this chapter showed that although printers printed hundreds of pamphlets, press time was occupied by larger projects. This allows for a reinterpretation of the evangelical pamphlet campaigns in the years following the Schmalkaldic War. Thomas Kaufmann and Nathan Rein demonstrated how important the pamphlet campaigns were in the ongoing Lutheran debates following Luther’s death in 1546 and in justifying the continued defiance against the Emperor to civic authorities. While the pamphlet campaigns were no doubt an important period in Magdeburg’s printing history, it is clear they were not the printers most active years nor was Magdeburg the largest print centre in the Empire. The methodology also reveals that Michael Lotter printed more than twice the amount than any other printer in Magdeburg during his career. He surpassed nearly all of his former competitors in Wittenberg and became one of the Empire’s leading printers. His focus on reprinting Luther’s writings and biblical translations, sometimes using false Wittenberg imprints, reveal how important reprinting Luther’s works was to Reformation printers and the significance of regional print centres in spreading evangelical ideas across the German-speaking world.

* All images in this chapter were available under the CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 International or the CC BY-SA 3.0 licenses.

Thomas Kaufmann, Das Ende der Reformation: Magdeburgs “Herrgotts Kanzlei”(1548-1551/2) (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2003); Kaufmann, ‘ “Our Lord God’s Chancery” in Magdeburg and Its Fight Against the Interim’, Church History, 73, no. 3 (2004), pp. 566–82; Nathan Rein, The Chancery of God : Protestant Print, Polemic and Propaganda Against the Empire, Magdeburg 1546–1551 (London: Routledge, 2016).↩︎

Walter G. Tillmanns, ‘The Lotthers: Forgotten Printers of the Reformation’, Concordia Theological Monthly, 22, no. 4 (April 1951), p. 260.↩︎

Magnus Hundt, Expositio Donati secundum viam doctoris sancti (Leipzig: Melchior I Lotter and Konrad Kachelofen, 1496). USTC 745874. Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, 4 Inc. c.a. 1315.↩︎

Orationes legatorum Francorum ad Venetos (Leipzig: Melchior I Lotter, 1495). USTC 741423. Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Res/4 J.publ.e 183.↩︎

Viaticus secudum chorum ecclesie misneñ feliciter (Leipzig: Melchior I Lotter, 1502). USTC 669076. Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, L.impr.membr. 10.↩︎

Christoph Reske, Die Buchdrucker des 16. und 17. Jahrhunderts im deutschen Sprachgebiet: auf der Grundlage des gleichnamigen Werkes von Josef Benzing (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2007), p. 516; Andrew Pettegree, Brand Luther: 1517, Printing, and the Making of the Reformation (New York: Penguin Press, 2015), p. 110.↩︎

WABr I, 425 n. 5. See also, Tillmanns, ‘The Lotthers’, p. 261.↩︎

Felician Gess, ed., Aktenund Briefe zur Kirchenpolitik Herzog Georgs von Sachsen, vol. I: 1517-1524 (Leipzig: Teubner, 1905), p. 641. Quoted in Pettegree, Brand Luther, p. 222.↩︎

Reske, Die Buchdrucker, p. 557.↩︎

Martin Luther, Von dem Bapst um tzu Rome: wider den hochberumpten Romanisten tzu Leiptzk (Wittenberg: Melchior II Lotter, 1520). USTC 702855; An den Christlichen adel Deutscher nation: von des Christlichen standes besserung: Luther (Wittenberg: Melchior II Lotter, 1520). USTC 632430; De captivitate Babylonica ecclesiae, praeludium (Wittenberg: Melchior II Lotter, 1520). USTC 629101.↩︎

Das Newe Tetament (Wittenberg: Melchior II Lotter for Lukas Cranach and Christian Döring, 1522). USTC 627911.↩︎

For a detailed look at the illustrations, see Peter Martin, Martin Luther und die Bilder zur Apokalypse: Die Ikonographie der Illustrationen zur Offenbarung des Johannes in der Lutherbibel 1522-1546 (Hamburg: Friedrich Wittig, 1983).↩︎

Das Allte Testament deutsch (Wittenberg: Melchior II Lotter and Michael Lotter, 1523). USTC 626765. Augsburg, Staats- und Stadtbibliothek, 2 Th B VII 10.↩︎

Steven Ozment, The Serpent and the Lamb: Cranach, Luther, and the Making of the Reformation (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2012), pp. 110-111.↩︎

Lotter’s wife was the daughter of Luther’s first cousin from his mother’s side (Lindemann). See Richard G. Cole, ‘Reformation Printers: Unsung Heroes’, The Sixteenth Century Journal, 15, no. 3 (1984), p. 333.↩︎

Dwaine Charles Brandt, ‘The City of Magdeburg before and after the Reformation: A Study in the Process of Historical Change’ (PhD Thesis, University of Washington, 1975), pp. 20-22.↩︎

Frederick and Ernest’s brother, Adelbart, was confirmed by Pope Sixtus IV to become Archbishop of Mainz when he came of age, but he died at sixteen.↩︎

Pettegree, Brand Luther, pp. 73-74. Part of the indulgence revenues was earmarked to pay fees for Albert’s appointment as Archbishop of Mainz. See Reinhold Kiermayr, ‘How Much Money Was Actually in the Indulgence Chest?’, The Sixteenth Century Journal, 17, no. 3 (1986), pp. 306-308.↩︎

Karl Janicke, ‘Burchard III., Erzbischof v. Magdeburg’, in Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie, vol. 3 (1876), pp. 559–561.↩︎

For an overview, see Friedrich Ebel, ‘Magdeburger Recht,’ in Matthias Puhle (ed.), Erzbischof Wichmann (1152-1192) und Magdeburg im Hohen Mittelalter (Magdeburg: Magdeburger Museen, 1992).↩︎

Rein, The Chancery of God, p. 13; Brandt, ‘The City of Magdeburg before and after the Reformation,’ pp. 22, 128. See also Oliver K. Olson, ‘Theology of Revolution: Magdeburg, 1550-1551,’ The Sixteenth Century Journal, 3, no. 1 (1972), pp. 56–79.↩︎

Missale Praemonstratense (Magdeburg: Bartholomaeus Ghotan & Lucas Brandis, 1479). USTC 741198. GW M24181.↩︎

Kaufmann, Das Ende der Reformation, pp. 32-33.↩︎

Johann von Schwarzenburn, Besweringe der olden duevelschen slangen mit dem goedtliken worde (Magdeburg: Michael Lotter, 1528). USTC 616179. Berlin, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Dg 1930/5.↩︎

Josef Benzing, Lutherbibliographie: Verzeichnis der gedruckten Schriften Martin Luthers bis zu dessen Tod (Baden-Baden: Heitz, 1966).↩︎

Luther, Ain gutte sermon am.XXjj.du soltt Got deinen Herren lieben (Wittenberg [=Augsburg]: Melchior Ramminger, 1526). USTC 609885. Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Res/4 Th.u. 103,XXVI,44.↩︎

For a detailed analysis of this practice across the Empire, see Drew Thomas, ‘Cashing in on Counterfeits: Fraud in the Reformation Print Industry’, in Shanti Graheli (ed.), Buying & Selling: The Business of Books in Early Modern Europe (Leiden: Brill, 2018), pp. 276-300.↩︎

Luther, Warninge an syne leven düdeschen (Wittenberg [=Magdeburg]: Michael Lotter, 1531). USTC 705987.↩︎

Luther, Wedder den muecheler tho dresen gedruecket (Wittenberg [=Magdeburg]: Michael Lotter, 1531). USTC 706250.↩︎

Luther, Das doepboekeschen vordudeschet up dat nye thogericht (Wittenberg [=Magdeburg]: Hans Barth, 1528). USTC 627045.↩︎

Luther, Offt me vor dem sterven flegen moege (Magdeburg: Hans Barth, 1527). USTC 679488.↩︎

Luther, Ein sendbrieff. Widder etliche rottengeister (Wittenberg [=Magdeburg]: Hans Walther, 1532). USTC 632439.↩︎

Luther (trans.), Dat Nye Testament (Magdeburg: Michael Lotter, 1532). USTC 628275.↩︎

De Propheten (USTC 631129) and De nye duedesche psalter mit den summarien (USTC 630705).↩︎

And it was often editions printed by his brother in Wittenberg that were the targets of counterfeiters.↩︎

Dat ander del des olden Testamentes (Wittenberg: Michael Lotter, 1531). USTC 628189.↩︎

See note 33.↩︎

Das Newe Testament (Wittenberg: Melchior II Lotter for Lukas Cranach and Christian Döring, 1522). USTC 627910.↩︎

Luther, Warninge an syne leven düdeschen (Wittenberg [=Magdeburg]: Michael Lotter, 1531). USTC 705987. Vienna, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, BE.4.V.28.(3) ALT PRUNK.↩︎

Klagerede vom glauben eines fromen und geistlichen (als es scheint) pharrhers fur dieser unser zeit itzt newlich gefunden und verdeudtschet (Wittenberg [=Magdeburg]: Hans Walther, 1544). USTC 670046. Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Polem. 407.↩︎

Kaufmann, ‘Our Lord God’s Chancery’, p. 574.↩︎

The top printing cities in the Empire between 1548 and 1550 were Magdeburg (301 publications), Nuremberg (297), and Wittenberg (278). Data from the USTC (accessed on 14 Oct 2018).↩︎

Kaufmann, ‘Our Lord God’s Chancery’, p. 574.↩︎

Ibid., p. 577.↩︎

Rein, The Chancery of God, p. 123.↩︎

Ibid., p. 20.↩︎

Ibid., p. 21.↩︎

Luther, Enchiridion. Der kleine catechismus (Magdeburg: Michael Lotter, 1554). USTC 650476.↩︎

Luther, Catechismus daruth de kinder lichtliken in dem lesende underwiset mögen werden (Magdeburg: Michael Lotter, 1531). USTC 620012.↩︎

Luther, Auslegung der Episteln und Evangelien vom Advent an bis auff Ostern. Anderweyt corrigirt. Auffs newe ubersehen aller text nach der newen dolmetzschung geendert (Magedburg: Michael Lotter, 1530). USTC 614248.↩︎

Luther, Auslegung der Episteln und Evangelien vom Advent an bis auff Ostern (Wittenberg: Michael Lotter, 1528). USTC 614281.↩︎

Luther, Auslegunge der Evangelien von Ostern bis auffs Advent gepredigt zu Wittemberg (Magdeburg: Michael Lotter, 1529). USTC 613947.↩︎

Kaufmann, ‘Our Lord God’s Chancery’, p. 569.↩︎

Ibid., pp. 572-73. While Magdeburg did print more editions than any other German print centre in 1549 and 1550, it is unclear why Kaufmann states that the period 1548-1552 represents a quarter of all printing during the century. In his table of ‘Magdeburger Drucke des 16. Jahrhunderts’ he lists 360 editions for the five-year period. That only represents 17.5% of the 2,054 editions he lists for the century. See Kaufmann, Das Ende Der Reformation, p. 563.↩︎

Luther, Cantiones ecclesiasticae Latinae (Magdeburg: Michael Lotter, 1545). USTC 613390; Luther, De husspostilla aver de Evangelia der Sondage und vornemesten feste dorch dat gantze jar (Magdeburg: Michael Lotter). USTC 629962; Biblia dat is de gantze hillige schrift oldes und nyen Testamentes uthgesettet in sassisch duedesch (Magdeburg: Hans Walther for Moritz Goltz, 1545). USTC 616662; and Johann Spangenberg, Uthlegginge der Episteln van Paschen an beth up den Advent… (Magdeburg: Christian I Rödinger, 1545). USTC 704686. VD16 and the USTC include multiple records of some these editions. I have determined these are different states of the same editions and have not counted them in the sheet totals for 1545, so as not to count the same sheets twice. Despite this, 1545 is still the highest year of production.↩︎

In 1549 the top cities in terms of sheets were Wittenberg, Nuremberg, Cologne, Leipzig, Strasbourg. and Magdeburg. Wittenberg’s sheet total was 1,976 compared to Magdeburg’s 566.5. In 1550 the top cities were Wittenberg, Nuremberg, Cologne, and Magdeburg. Wittenberg’s sheet total was 2,916, compared to Magdeburg’s 728. The totals for 1550 are less certain, as being the mid-century mark, it is a popular inferred date for editions not listing the year. For more on this sheet analysis, see Drew Thomas, ‘The Industry of Evangelism: Printing for the Reformation in Martin Luther’s Wittenberg’ (PhD thesis, University of St Andrews, 2018). http://hdl.handle.net/10023/14589↩︎

Hans J. Hillerbrand, ‘Was There a Reformation in the Sixteenth Century?’, Church History, 72, no. 3 (2003), p. 526↩︎

Spangenberg, Postilla duedesch. Vor de yungen Christen knechte unde megede yn fragestuecke vorvatet. Van Paschen beth up den Advent (Magdeburg: Michael Lotter, 1549). USTC 685134.↩︎

Biblia: dat ys de gantze hillige schrifft vorduedeschet (Magdeburg: Michael Lotter, 1554). USTC 616689.↩︎

Two concerns with this analysis are the issues of survival bias and print runs. Big books are more likely to survive than smaller books. However, during this analysis’ time period, the industry was heavily focused on Reformation printing. Works by Luther were collected even during his lifetime and are much more likely to have survived to the present day, which I think insulates Magdeburg. As for print runs, this chapter’s conclusion would be challenged if smaller books had much larger print runs than larger books. However, that is highly unlikely, because it would be economically wiser for a printer to underestimate the popularity of a pamphlet because it could be reprinted so quickly, rather than overestimating and having unsold stock.↩︎

Biblia das ist die gantze heilige schrifft Deudsch (Wittenberg: Hans Lufft, 1534). USTC 616653.↩︎

Thomas, ‘The Industry of Evangelism’, p. 198.↩︎

Apocrypha. Dat synt boeker de der hilligen schrifft nich gelick geholden unde doch nuette unde gudt tho lesende synt alse noemliken (Magdeburg: Michael Lotter and Ambrosius I Kirchner, 1555). USTC 612341.↩︎